- Bill Gates Accepts Hunger Award, Says Focus on Poor Farmers “More Important Than Ever“. Go Bill!

- Small farmer in Mozambique doing well by doing good.

- Ancient Romans drank in South Tyneside. What else was there to do?

- Ancient Americans moved down the coast. That’s where the food was.

- Rewarding excellent chocolate from smallholder farmers.

- Food & Communication: Recipes for Development. IFPRI plays TED on Thursday.

- Climate change adaptation and mitigation: just do it! A. Jarvis comes out storming.

- West African farmers ‘already adapting to climate change’. A. Jarvis picks up his ball and goes home.

- Desperately seeking heirloom apples in Idaho.

Heirlooms for entrepreneurs

Pollin8r (geddit?)! An “open access photo bank of heirloom produce” and “an inventive new web-based project … that promises to connect heirloom-produce loving eaters to farmers willing to grow heritage produce — all with just the click of a mouse”. Bring it on? Bring it up?

Please, sir, what is an heirloom?

IRRI gets groovy

More research on agriculture needed

Nature News reports on a meeting last week hosted by Jeff Sachs at Columbia University in New York. The idea was to create a global agriculture monitoring network, something he’s been promoting for a while, and all the big guns were there. 1 Sachs told the meeting that scientists “simply do not have the data they need to properly explore” how agriculture has changed the world. “We want to understand ecosystems and the people who are living in them,” Sachs said.

Good thinking. Sandy Andelman, of Conservation International, told the meeting about a pilot project in Tanzania.

In addition to basic environmental data about soils, nutrients and land cover, the project tracks agricultural practices. It also incorporates data about income, health and education that is maintained by the government. Andelman says that … initial results from the project have already prompted the Tanzanian government to adjust the way it zones agricultural land in the area.

That does sound good. I wonder, though, do the “agricultural practices” Andelman monitors have anything on the deliberate use of specific agricultural biodiversity to buffer against environmental shocks, or to enhance resilience in the face of pests and diseases, or to adapt to climate change? Maybe, though I’m not holding my breath. When Sachs first floated the idea, on which Andelman was a co-author, Luigi noted that it didn’t “mention the desirability of monitoring levels of agricultural biodiversity on-farm”.

Some of the meeting attendees want to go slow. The Gates Foundation thinks “a dozen or so” would be a good start to “get the ball rolling”. Sachs wants more. Nature News says he envisages “500 sites within two or three years”.

“We need to get this thing up and running,” he says, warning of the perils of endless organizational meetings. “I don’t want to spend ten years on this.”

Agreed, but it would be even worse, in my opinion, to build such a network, even if it does take 10 years, and not monitor the amount of agrobiodiversity and how farmers make use of it.

Seems like all that rice breeding was worth it after all

ACIAR has just published a huge study of the impact of IRRI’s rice breeding work in SE Asia. The press release has the key numbers:

- “Southeast Asian rice farmers are harvesting an extra US$1.46 billion worth of rice a year as a result of rice breeding.”

- “…IRRI’s research on improving rice varietal yield between 1985 and 2009 … [boosted] … rice yield by up to 13%.”

- “…IRRI’s improved rice varieties increased farmers’ returns by US$127 a hectare in southern Vietnam, $76 a hectare in Indonesia, and $52 a hectare in the Philippines.”

- “The annual impact of IRRI’s research in these three countries alone exceeded IRRI’s total budget since it was founded in 1960.”

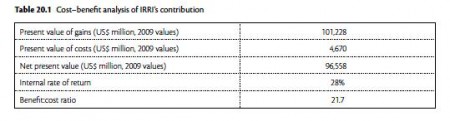

But I guess the figure the Australians were really after is that in the final table:

A pretty decent return.

Good to see the pioneering work of IRRI (and others) in documenting pedigree information in a usable way recognized — and indeed made use of. And good to see the International Network for Genetic Evaluation of Rice (INGER) and its use of the International Treaty’s multilateral access and benefit sharing system highlighted in the study as a model for germplasm exchange and use. Of course one would have loved to see the genebank’s role in producing the impact also recognized, rather than sort of tacitly taken for granted as usual, but maybe the data can be used to bring that out more in a follow-up.

I see another couple of opportunities for further research, actually. There is little in the study about the genetic nature of the improved varieties that are having all this impact. To what extent can their pedigrees be traced back to crop wild relatives, say? And, indeed, how many different parent lines have been involved in their development, and how genetically different were they? That will surely to some extent determine how sustainable these impressive impacts are likely to be.