An über-narrative that pulses at the heart of the “conservation for use” genetic resources body is the one about the accession that saved the planet. Some sample, preferably of an unprepossessing, weedy individual that otherwise wouldn’t merit more than a glance, turns out to have the gene that confers resistance to a disease, or boosts the content of something or other. Breeders, after a long search and an almighty struggle, transfer the gene into suitably modern varieties which are unleashed on a grateful world just in time to avoid certain disaster. It helps if the saviour sample can boast a biographical tidbit, such as saved by a nonagenarian grannie, or identified while the collector cast his eye about during a yak butter tea break in the Hindu Kush.

We’ve got a million of them, from Hessian flies to tomato solids to dwarfing genes to double-low canola to non-bitter cucumbers to [insert your favourite here].

And then there’s the one about nematode resistance in beets, mostly sugar beets, a new one on me. I was recently tasked to find out more about this particular story, with very little to go on beyond the taskmaster’s hazy memory of the standard über-narrative. A little inspired Googling led me to Pre-breeding for nematode resistance in beet, by W. Lange and Th. S.M. De Bock, who helpfully relate that:

Resistant plant materials originated from the annual accession PI 198758 of B. vulgaris subsp_ maritima, which had been collected in Le Pouliguen, Brittany, France.

Paydirt! And the inclusion of a PI number suggests that this came from the USDA’s genebank system, to which I hurried for more information. ((Why, I do not know. Perhaps in search of a more interesting biographical tidbit to spice up my narrative.))

However, and this is where it gets complicated, a search for PI 198758 at USDA’s GRIN says that it was collected by G. Coons, of the USDA Tobacco and Sugar Crops Research Branch, at Coimbra in Portugal some time between 1946 and 1951. (It is also not currently available, but that’s a separate story). But — more paydirt! — PI 198759, the very next accession, was indeed collected by Coons at Le Pouliguen in France.

Further Googling took me to the Sugarbeet Research Unit at Fort Collins, who were kind enough to answer my questions about which accession — 198758 or 198759 — should star in the narrative.

“In 1987 I received from IRS, Bergen op Zoom, ((“The research and knowledge centre for sugar beet growth in the Netherlands.“)) a packet of seed that was labelled Le Pouliguen Group 2, Pi 198758-59. I also tried to figure this number out and have concluded that its meaning is different from PI as used by GRIN. I think it was a code used by IRS meaning 1987 seed lots 58 and 59.”

Well, maybe … but that really does seem like way too much of a coincidence, that a sample harvested in The Netherlands in 1987, and that came from Le Pouliguen, or has an accession from Le Pouliguen in its pedigree, should happen to end up with the same number as one collected at Le Pouliguen between 1946 and 1951. I mean, it’s possible, but …

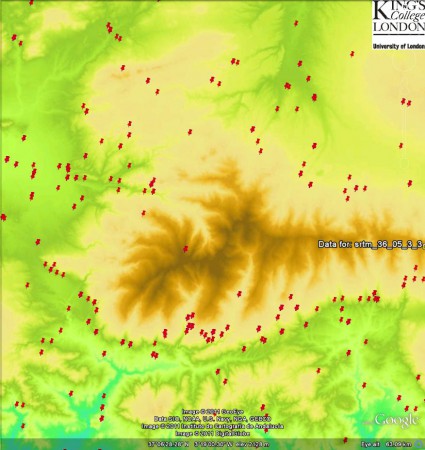

Something weird has happened along the way, I suspect. Other evidence from the beet breeders at Fort Collins suggests that Le Pouliguen is the correct location, because other accessions that showed partial resistance to nematodes came from the Loire estuary. Did Lange and De Bock make a mistake in their number? Did GRIN record the wrong collection location for PI 198758? Who knows?

And a final question: am I going to let any of this truth-seeking have any impact on my narrative?

No. But it sure was fun, and it isn’t often you get to say that about trips into GBDBH.

You heard of

You heard of