It’s clear genebanks around the world are having a hard time. The poster child just at the moment is Pavlovsk, of course. But we’ve heard lately that Australia’s genebanks are also threatened. And we’ve also been following a similar situation over the past several months at Wellesbourne in the UK. Why is this happening? As chance would have it, I think a couple of recent posts here may hold some clues.

I think, for example, that our failure in the genetic resources conservation community to quantify — or at least communicate — costs properly is not, er, helping. And we still have a long way to go in facilitating the process of getting conserved material where it is most needed. So, maybe we’ve also seen in the past few days the answer to genebank funding. But that doesn’t mean we can ease up on getting our costs straight, and getting our material known and out there, which among other things means sorting out Genebank Database Hell.

Well, there’s another thing. We do also need to admit to ourselves that maybe, just maybe, not all genebanks are necessary. I hope Pavlovsk, the Australian genebanks and Wellesbourne survive and thrive. It will set a bad precedent if they go under, a very bad precedent, and in any case a genebank is more than just brick, mortar and seeds. It’s people and expertise, and we should fight for them. But if it’s not to be, I hope at least the unique material they have been conserving so diligently for so long makes its way speedily and safely to some other home, where its long-term conservation and availability will perhaps be better ensured.

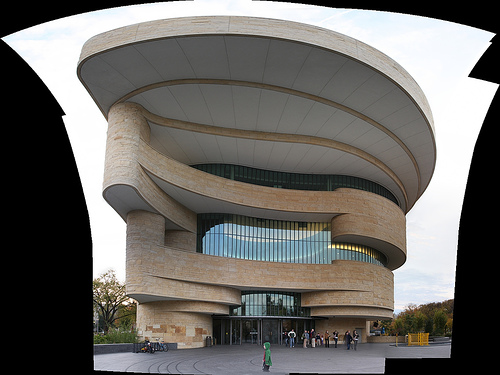

A Native American food garden has been planted along the pavement by the side of the building. You can see maize and squash here on the left.

A Native American food garden has been planted along the pavement by the side of the building. You can see maize and squash here on the left. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find anything about this on the museum’s website, so I don’t know whether it is a temporary exhibit or a permanent feature. Anyway, I wonder if the next donation by that Connecticut tribe might be to some of the

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find anything about this on the museum’s website, so I don’t know whether it is a temporary exhibit or a permanent feature. Anyway, I wonder if the next donation by that Connecticut tribe might be to some of the