- The Ethicurean digs into agretti (Salsola soda).

- Pavlovsk in the St Petersburg Times …

- … and in the Sydney Morning Herald.

- Conference in November: Nutrition Security in the Developing World ABD?.

- CIAT’s library showcases nutrition.

- More on turkey domestication.

A novelist on Pavlovsk and hunger

Elise Blackwell wrote a novel — Hunger — about the Siege of Leningrad and the people who starved at the Vavilov Research Institute rather than eat the seeds in their care. I haven’t read it, yet, although I have read interviews with the author. The Atlantic asked her to reflect on what is going on at the Pavlovsk Experiment Station. Very clever.

Genetic diversity is crucial to human survival and food is a central part of our history and heritage, but aesthetics matter too. In the place of an apple famed for its winter heartiness and a berry prized for its perfect sweetness will sit a commercial real estate development, the money earned off the bulldozed land going to those who successfully claimed in court that the Pavlovsk collection does not exist because it was never officially registered. Soon they will be accurate in more than legalistic terms: it won’t exist.

One thing puzzled me about her piece, though, and that was a reference to a bean she once grew, which she calls “the Tarahumara carpenteria,” italicized just like that, which suggests it could be a genus and species, but with a definite article, which suggests that if it is, Blackwell doesn’t know how to use a binomial. ((And why should she; I couldn’t write a novel.)) I know of the Tarahumara people, and I have grown one of their heirloom sunflowers. But I could find no trace of this bean either in the interwebs or in my copy of the 2010 Seed Savers Yearbook. Blackwell doesn’t indicate what kind of bean it might have been: bush or pole; common, runner, lima or tepary. I checked them all. It isn’t there. I checked the USDA. It isn’t there. I checked Native Seeds/SEARCH. It isn’t there. Please, someone, tell me I am wrong.

This is not to cast doubt on anything Elise Blackwell wrote. Really. It is to suggest two things. First, if anyone is still growing a bean called anything like Tarahumara carpenteria, would they please, please ensure that someone else has it too, and not just as memory-laden specimens for weighting down pie crusts. And secondly, as someone long ago once told me; “write it down, because the weakest ink lasts longer than the strongest memory.” ((Or did I read it somewhere? A self-referential footnote.))

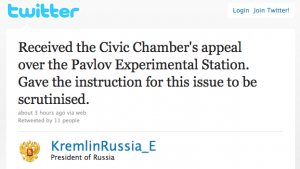

We’all speak, they listen?

Nibbles: Pavlovsk, Pavlovsk, Pavlovsk, Fun fungus, ALVs, Breadfruit

- Best round up yet of what’s happening at Pavlovsk Experiment Station.

- Nature’s report on Pavlovsk is good too.

- Pavlovsk making waves in India too. S.Ananthanarayanan shares a write-up in The Statesman, Kolkata.

- More on that Chinese insect-eating fungus, or Chinese Love Flower. Yuck.

- A one-woman crusade for traditional African leafy vegetables. Right.

- Breadfruit trees in Jamaica. From the Trees that Feed Foundation, a new one on me.

Nibbles: Bent, Rice, Cheez, Pavlovsk, Millennium Seed Bank, Livestock, EUCARPIA

- Fine memoir of Sir Bent Skovmand. Thanks Dag.

- Rice yields falling — and not just in experimental stations. The paper.

- In all the eulogies to the inventor of the Cheez Doodle, a note of truth.

- You could buy the Pavlovsk genebank site for just USD3.3 million, it says here. Is that even doable?

- Meanwhile, over in England, Researchers Rush to Fill Noah’s Ark Seed Bank While Politicians Bicker.

- Meanwhile, in Australia, worries about declines in livestock diversity.

- EUCARPIA’s meetings calendar. Handy.