A user gets stranded in Genebank Database Hell looking for Vavilov’s collections in Tunisia. Not for the fainthearted.

Nibbles: CWR protected, Aquaculture, Super potato, Maize domestication, Climate in Africa, Zimbabwe, Pepper, Chinese genebank

- Indian tiger park protects crop wild relatives and other useful plants. h/t Danny.

- CAPRi News highlights a book about Asian Aquaculture Successes.

- Precision breeding creates super potato. Yeah, if you want an industrial feedstock, not food.

- Maize moved from hand to hand, not with moving farmers. And that means … ?

- An African view of climate change. Complex.

- Zimbabwe’s advice on climate change: “Plant more sorghum, less maize“. Simple.

- Survival farming in Zimbabwe. Hard.

- Small farmers growing Piper pepper in Vietnam

- China has set up its first national seed bank as part of the country’s efforts to protect biodiversity. I’ve been there, says Jeremy, and it is stunning.

Bent Skovmand remembered

A Facebook post by Dag Endresen of NordGen alerted me to the recent publication of the biography of Bent Skovmand, entitled The Viking in the Wheat Field: A Scientist’s Struggle to Preserve the World’s Harvest. Bent Skovmand (1945-2007), a student of Norman Borlaug, was a very influential figure in the world of conservation and use of crop genetic resources in general, and of wheat in particular. The director of the Nordic Gene Bank (now NordGen) when he died, the books he kept in his office are touchingly maintained at NordGen’s Alnarp headquarters as a separate collection. I’ll be trying to get hold of the book.

Barley mutants take over world

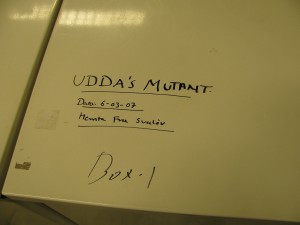

Sometimes nature needs a little help. That was brought home to me in emphatic fashion last week as I listened to the formidable Udda Lundqvist summarize her more than half a century making and studying barley mutants. Some 10,000 barley mutants are conserved at NordGen. In this freezer, in fact:

And Udda described some of the main ones during her talk. You can see some of them, and read all about this work, in her 1992 thesis.

Useful mutations in barley include a wide range of economically important characters: disease resistance, low- and high-temperature tolerance, photo- and thermo-period adaptation, earliness, grain weight and -size, protein content, improved amino acid composition, good brewing properties, and improved straw morphology and anatomy in relation to superior lodging resistance.

Some of these have found their way into commercial varieties.

Through the joint work with several Swedish barley breeders (A. Hagberg, G. Persson, K. Wiklund) and other scientists at Svalöf, a rather large number of mutant varieties of two-row barley were registered as originals and commercially released (Gustafsson, 1969; Gustafsson et al., 1971). Some of them have been of distinct importance to Swedish barley cultivation. Two of these varieties, ‘Pallas’, a strawstiff, lodging resistant and high-yielding erectoides mutant, and ‘Mari’, an extremely early, photoperiod insensitive mutant barley, were produced directly by X-irradiation.

Udda is in her 80s but shows little sign of slowing down.

Nibbles: Ecosystem services, Breadfruit, Oneida corn, Teff

- Map your own ecosystem services.

- Diane’s Garden: the story of the world’s largest breadfruit collection.

- Oneida people rediscover their traditional white corn varieties.

- White folks discover Ethiopian grain. “Teff is tasty, cute, expensive, temperamental, and enigmatic.”