![]() Evolutionary Anthropology has a nice paper summarizing the history of domestic cattle, based on the latest molecular marker data. 1 Unusually, the authors at least attempt a flowing account of the origin and spread of a domesticated species, and even more unusually actually achieve it in places. Alas, the details of haplogroups and mtDNA vs Y-chromosome markers will keep intruding. Someone will write a review paper some day which gets the geeky stuff of summarizing all the molecular and other data out of the way upfront, and then just tells the story of domestication and dispersal as the old-fashioned, and no doubt now out of fashion, narrative historians used to do. Rather than annoyingly mixing up the two.

Evolutionary Anthropology has a nice paper summarizing the history of domestic cattle, based on the latest molecular marker data. 1 Unusually, the authors at least attempt a flowing account of the origin and spread of a domesticated species, and even more unusually actually achieve it in places. Alas, the details of haplogroups and mtDNA vs Y-chromosome markers will keep intruding. Someone will write a review paper some day which gets the geeky stuff of summarizing all the molecular and other data out of the way upfront, and then just tells the story of domestication and dispersal as the old-fashioned, and no doubt now out of fashion, narrative historians used to do. Rather than annoyingly mixing up the two.

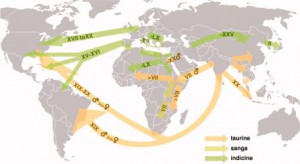

Anyway, that story can be summarized for cattle in one map, and here it is:

Which is cool enough. But actually what stays in the mind — or, at any rate, my mind — is, as ever, the little things. Here are three that did it for me.

First, a rare attempt to link up genetic patterns in a domesticated species and the associated human population:

Four ancient Tuscan breeds all had haplotypes also found in Anatolia, near the sites of domestication. [This] … may indicate a secondary migration from Anatolia to Italy, [which] … would be in line with the classical accounts of Etruscans arriving in Italy from either Lydia or the isle of Lemnos. An Etruscan representation of cattle resembles the semi-feral Maremmana cattle in southern Tuscany. Interestingly, inhabitants of two small Tuscan cities with Etruscan origins also had southwest-Asian mtDNA signatures.

Second, a simple historical explanation for a fairly obvious feature of modern European cattle diversity, to wit, that there isn’t much of it in the Netherlands.

Seventeenth-century Dutch paintings show cattle with a large variety of coat colors. After three catastrophic rinderpest epidemics in the eighteenth century, cattle herds were repopulated by mass imports of black-pied cattle from the Holstein region.

And finally, the story of the Brazilian zebu herd, which caught my eye because of the reference to it in a recent Economist article.

This started during the nineteenth century with the purchase of a few animals and was followed by mass imports of Guzerat (1975), Gir (1890), and Ongole (1895, in Brazil denoted as Nelore) animals to improve the national herds. The same zebu breeds were also imported into the U.S. These imports consisted mainly of bulls. The percentage of animals with zebu mtDNA varies in Brazil from 37% in the Gir breed to 43% in the Nelore and 69% in the Guzerat breeds. As shown by the distribution of the indicine Y-chromosomes and microsatellite analysis, zebu bulls were crossed in several South American Criollo populations… Today, Brazil holds the largest commercial cattle population worldwide, with 200 million heads. Together with descendants of other indicine and taurine imports, Nelore make up the bulk of this intensively managed population.

You see what I mean about the geeky stuff interrupting the flow, right? Anyway, the particularly fun detail about this Brazilian zebu story is the fact that one Nelore bull, called Karvadi, “became the ancestor of thousands of Brazilian zebu cattle.” There’s a photograph of him in the paper, courtesy of the Archives of the VR Artificial Insemination Center, Araçatuba, and very handsome he is too.