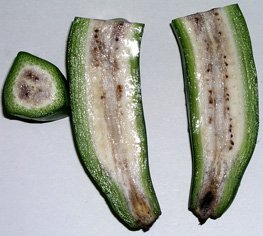

Somewhere this morning I read something silly from a conservation whiner that the mainstream media would pay more attention to Paris Hilton taking a pee in South Africa, or 10 murders, than the loss of 10 wild species. I didn’t even bother to bookmark it, so familiar was the sentiment. To redress the balance, here’s an entirely new banana cultivar, heretofore unknown to science, spotted by Luigi on the proMusa website and shared with the world via Twitter. It was collected in Oman in 2003 or 2004 and grown on in Germany. I’m not sure yet what it is good for, although it is drought resistant. And “[t]he authors speculate that the variety, which they named Umq Bi’r, might have reached Oman many centuries ago via Zanzibar, Madagascar or the Comoros”. More interesting than Paris Hilton taking a pee? You bet!

Somewhere this morning I read something silly from a conservation whiner that the mainstream media would pay more attention to Paris Hilton taking a pee in South Africa, or 10 murders, than the loss of 10 wild species. I didn’t even bother to bookmark it, so familiar was the sentiment. To redress the balance, here’s an entirely new banana cultivar, heretofore unknown to science, spotted by Luigi on the proMusa website and shared with the world via Twitter. It was collected in Oman in 2003 or 2004 and grown on in Germany. I’m not sure yet what it is good for, although it is drought resistant. And “[t]he authors speculate that the variety, which they named Umq Bi’r, might have reached Oman many centuries ago via Zanzibar, Madagascar or the Comoros”. More interesting than Paris Hilton taking a pee? You bet!

Goats in peril

A plea arrives from Australia, concerning the goats of Middle Percy Island, a paradisiacal spot off the coast of Queensland on the Great Barrier Reef. These goats, it seems, are the descendants of animals released on the islands 200 years ago to provision passing sailors. They still do. The thousands of “yachties” who drop anchor at Middle Percy each year could buy expertly tanned goat skins and stock up on goat stew (and other goodies) all prepared by the people who hold the lease on Middle Percy. In a few weeks, however, the lease is due to revert to Queensland’s Department of Environment and Resource Management. They have apparently threatened to cull all the goats (although there’s nothing about that on the DERM website) or maybe all the goats except those that can survive on 140 Ha of the island.

“These goats need to be protected or domesticated — not annihilated” says my informant. “They have lived in the tropics and have foraged for themselves for two centuries.” As a result, “the genetic heritage among this small goat population which, by its very isolation, could potentially be crucial in providing genetic traits to goat populations in tropical Third world countries in need of calcium” could vanish.

Is that true? I simply don’t know. The history and current status of Middle Percy Island is complicated enough without even bringing the goats on board. Get into the livestock and it becomes more complicated still. The first European explorer, Matthew Flinders, noted “no marsupials were inhabiting Middle Percy Island” when he was there in 1802, and he is believed to have left behind the first of the goats. Subsequently settlers on the island brought their own herds, probably Saanen and British Alpine types. In the 1920s a herd of 2000 sheep was established. And in 1996 a senior BBC producer noted sheep, kangaroos, a solitary emu and a small herd of Indian cattle in addition to the goats.

One of the current leaseholders says they “have identified a variety of different types of goat, which seem to breed true to form; Cashmere, Saanen, British-Alpine, Australian All-black the Melaan, and possibly Toggenburg and an All-brown goat.” It would indeed be interesting if all these types were maintaining their distinctive looks despite their freedom to choose their own mates.

Will the Department of Environment and Resource Management really try to annihilate all the interloper species, including fruits and vegetables and bees and poultry brought in to sustain the settlers? Or have they just got it in for the goats? Could the goats be managed to keep populations at a level low enough not to damage the environment? Would those population levels preserve the genetic diversity of the goats? And is that diversity important anyway?

Lots of questions, no answers. But at least the questions are now being asked, and if answers are forthcoming we’ll be sure to bring them into the conversation.

Nibbles: Biofuels, No-till corn, BBTV, Coffee pest, Air potato, Neolithic, Turkish roses, Cowpea conference

- Science: Biodiversity is good even for biofuels.

- Science: Lack of annual diversity is bad for no-till maize (corn).

- Science: “Dead” bananas can still transmit banana bunchy top virus BBTV.

- Science: Potential biological control identified for coffee berry borer. (Eeeyew warning.)

- Art: Biological control (Lilioceris near impressa) of air potato (Dioscorea bulbifera). (Gorgeousness warning.)

- Science: Farmers brought farming to Britain.

- Science and art: A rose is a rose is a rose.

- Science: Black-eyed peas in Dakar gig.

Nibbles: Potatoes, beef, lamb, bull

- Want potato diversity? In the US? Tom Wagner’s your man.

- I should do more than nibble Gary’s insightful views on extremism, especially in relation to grass-fed beef and a bit of biochar. But hey, it’s Sunday.

- George Orwell contemplates smoking mutton. Jeremy asks: “Can anyone tell me more about acatie, from the Savoie?”

- The Scientist Gardener dives into bull semen. Love that second footnote!

Nibbles: Old lentil, Cassava pests, Gates the reconciler, Gardeners

- 4000 year old lentil sprouts.

- It looks bad for cassava in SE Asia.

- Bill Gates speaks out on sustainability and productivity.

- “Gardeners must unite to save Britain’s wildlife.” We say: what about Britain’s landraces?