- Symbiotic fungus can help plants and detoxify methylmercury.

- Very attractive book on the wild tomatoes of Peru. I wonder if any of them eat heavy metals.

- There’s a new dataset on the world’s terrestrial ecosystems. I’d like to know which one has the most crop wild relative species per unit area. Has anyone done that calculation? They must have.

- Iran sets up a saffron genebank. Could have sworn they already had one.

- The Natural History Museum digs up some old wheat samples, the BBC goes a bit crazy with it.

- Paleolithic diets included plants. Maybe not wheat or saffron though.

- Community seedbanks are all the rage in Odisha.

- Seeds bring UK and South Africa closer together. Seeds in seedbanks. Not community seedbanks, perhaps, but one can hope.

- Can any of the above make agriculture any more nutrition-sensitive? I’d like to think yes. Maybe except for the mercury-eating fungus, though you never know…

Brainfood: Coconut in vitro, Clean cryo, Chickpea & lentil collections, Genebank data history, Eurisco update, Mining genebank data, TIK, Sampling strategy, Drones, GIS, Mexican CWR, Post-2020 biodiversity framework

- Thiamine improves in vitro propagation of sweetpotato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] – confirmed with a wide range of genotypes. Getting there, keep tweaking…

- Minimizing the deleterious effects of endophytes in plant shoot tip cryopreservation. Something else to tweak.

- Ex Situ Conservation of Plant Genetic Resources: An Overview of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) Worldwide Collections. Thankfully not much in vitro and cryo involved. The main tweak necessary is to share more characterization data with breeders.

- Data, Duplication, and Decentralisation: Gene Bank Management in the 1980s and 1990s. Ah, but do calls for more data also reflect attempts to cut costs and build political bridges? And would that be so bad?

- EURISCO update 2023: the European Search Catalogue for Plant Genetic Resources, a pillar for documentation of genebank material. Arguably, Eurisco tries to do all of the above, and pretty well.

- Bioinformatic Extraction of Functional Genetic Diversity from Heterogeneous Germplasm Collections for Crop Improvement. You need fancy maths to make sense of all that data. And use it.

- Research Status and Trends of Agrobiodiversity and Traditional Knowledge Based on Bibliometric Analysis (1992–Mid-2022). Not much traditional knowledge in those databases, though, eh? That would be one hell of a tweak.

- Species-tailored sampling guidelines remain an efficient method to conserve genetic diversity ex situ: A study on threatened oaks. Meanwhile, some people are still trying to figure out the best way to tweak sampling strategies to add diversity to genebanks. Spoiler alert: you need data on individual species.

- Collecting critically endangered cliff plants using a drone-based sampling manipulator. You also need drones.

- Application of Geographical Information System for PGR Management. One thing you can do with all that data is map stuff. So at least the drones know where to go.

- Incorporating evolutionary and threat processes into crop wild relatives conservation. The only thing that’s missing from this is traditional knowledge. And maybe drones.

- Conserving species’ evolutionary potential and history: opportunities under the new post-2020 global biodiversity framework. All these data will allow us to measure how well we’re doing. And whether we can ask for cryotanks, drones, and better databases.

Brainfood: Diversity & stability, Diversity & profitability, Rotations, Food environments, Food system transitions, Deforestation & ag, Great Lakes priorities, Translational research, Field size, Genetic erosion

- Consistent stabilizing effects of plant diversity across spatial scales and climatic gradients. More species-diverse communities are more stable. Ok, what about agricultural systems though?

- Financial profitability of diversified farming systems: A global meta-analysis. Total costs, gross income and profits were higher in diversified systems, and benefit-cost ratio similar to simplified systems. No word on stability, alas.

- Global systematic review with meta-analysis reveals yield advantage of legume-based rotations and its drivers. Integrating a legume into your low-diversity/low-input cereal system can boost main crop yields by 20%. I wonder if this meta-analysis was included in the above meta-analysis. Again, no word on stability though.

- The influence of food environments on dietary behaviour and nutrition in Southeast Asia: A systematic scoping review. It’s the affordability, stupid. Should have gone for more diversified farming I guess :)

- Global food systems transitions have enabled affordable diets but had less favourable outcomes for nutrition, environmental health, inclusion and equity. Well according to this, industrialised farming (ie simplification) has led to more affordable diets. But we know from the above that diversification can be profitable. So it was the wrong kind of simplification? Can we diversify now and maintain affordability while also improving nutrition, environmental health, inclusion and equity? Wouldn’t that be something.

- Disentangling the numbers behind agriculture-driven tropical deforestation. Ending deforestation is not enough. The resulting agriculture must be diversified in the right way too, I guess.

- Strategizing research and development investments in climate change adaptation for root, tuber and banana crops in the African Great Lakes Region: A spatial prioritisation and targeting framework. Diversifying with drought-tolerant bananas and heat-tolerant potatoes is all well and good, but you also have to know where exactly to diversify, and here’s how.

- Translational research in agriculture. Can we do it better? Difficulty developing drought-tolerant bananas and heat-tolerant potatoes? Get more diverse peer-reviewers.

- Increasing crop field size does not consistently exacerbate insect pest problems. When you diversify, don’t worry too much about making fields bigger.

- Genetic diversity loss in the Anthropocene. You can predict change in genetic diversity from change in range size, and the average is about a 10% loss already. Ok, what about agricultural systems though? Wait, isn’t this where we came in? My brain hurts…

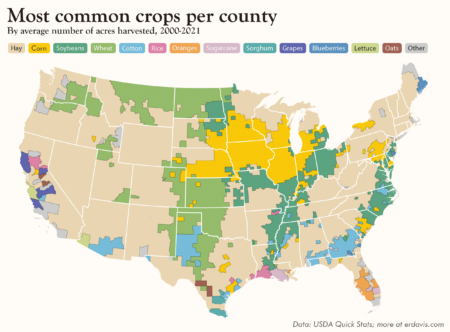

New crop of crop maps crops up

Data viz wiz Erin has a bunch of excellent new maps of crop distributions in the USA over on her website. The data come from USDA Quick Stats, but her maps are way cooler. This, for examples, shows very strikingly what a powerhouse of agricultural biodiversity California is. Though I guess southern Texas comes close.

Brainfood: Trade double, Organic farming, Food vs non-food, Wild plants, Wheat yields, CWR in S Africa, Gene editing, European seed law, Farm diversity

- Agricultural trade and its impacts on cropland use and the global loss of species habitat. Rich countries have a large biodiversity footprint outside their borders because they import a lot of agricultural products from areas where biodiversity is disappearing fast.

- International food trade benefits biodiversity and food security in low-income countries. Ah, but low-income, high biodiversity countries import a lot too. I really don’t know what to think about trade now. Nicely parsed by Emma Bryce.

- Biodiversity and yield trade-offs for organic farming. Biodiversity gain and yield loss balance each other out. Oh, come on scientists, would it kill you to give a definite answer?

- Crop harvests for direct food use insufficient to meet the UN’s food security goal. We should definitely use more cropland for actual human food. But that would probably not be good for exports, no? Uff.

- The hidden safety net: wild and semi-wild plant consumption and dietary diversity among women farmers in Southwestern Burkina Faso. Yeah, but who needs crops and imports anyway.

- Six decades of warming and drought in the world’s top wheat-producing countries offset the benefits of rising CO2 to yield. In any case, crops are in trouble.

- Planning complementary conservation of crop wild relative diversity in southern Africa. But CWR will save crops if only we can conserve them.

- Genome Editing for Sustainable Agriculture in Africa. Especially if we use the latest toys.

- Impact of the European Union’s Seed Legislation and Intellectual Property Rights on Crop Diversity. And have all the right policies in place.

- Farm-level production diversity and child and adolescent nutrition in rural sub-Saharan Africa: a multicountry, longitudinal study. But actually, it’s livestock we really need.