- The latest genomic whiz-bangery.

- CIFOR’s Congo slideshow makes The Guardian. About as far from genomic whiz-bangery as you can get.

- Speaking of which… Very long talk by David Tilman. Almost certainly worth watching in its entirety. Eventually. It all depends on trade-offs. See what I did there?

- Agriculture stops expanding. Is it all that genomic whiz-bangery?

- U. of Delaware gets big Lima bean grant. Yes, Delaware. They got whiz-bangery in Delaware too.

- Meanwhile, Texan cotton breeder gets award. For a certain amount of whiz-bangery.

- Translocation and restoration: cool, but a last resort, whiz-bangery says.

- Support for the seed sector in S. Sudan. Any landraces? No whiz-bangery in sight.

- And likewise for the yam bean in Africa.

- Wonder whether that’ll be on the agenda at the First Food Security Futures Conference in April. Probably not.

- Nor, probably, will anyone be thinking too hard about agro-ecology; but you could be, with this handy-dandy introduction to holistic management.

- SEAVEG; no, not nori etc, but veg in SE Asia.

- Different animals need different kinds of fodder, ILRI shows how.

- Wishing success to the Indigenous Food and Agriculture Initiative launched at the University of Arkansas today.

What’s gin got to do with the price of corn?

Just caught up with a fascinating NPR interview with Richard Barnett, author of The Book of Gin. What struck me particularly was a section on the origins of the gin boom in England. Barnett tied it to The Glorious Revolution, and William of Orange coming to the throne. William needed to keep the land-owning aristos sweet. One way to do that was to keep the price of grain high, and one way to do that was to deregulate distilling. That, as Barnett explained, opened up a new market for grain, which kept grain prices high, even as it made gin cheaper and cheaper.

So the aristos were presumably happy enough to keep supporting King Billy, and there NPR left it to wander down Gin Lane and beyond.

But the story sounds an awful lot like the contemporary story of mandated maize biofuel. That too opens up a new market that keeps prices high, and, some say, is keeping food prices high too.

So here’s my question: did the demand for grain for distilling have any impact on food prices in the 18th century?

Brainfood: Climate in Cameroon, Payments for Conservation, Finger Millet, GWAS, Populus genome, miRNA, C4, Cadastres, Orange maize, Raised beds, Contingent valuation, Wild edibles, Sorghum genomics, Brazilian PGR, Citrus genomics

- Climate and Food Production: Understanding Vulnerability from Past Trends in Africa’s Sudan-Sahel. Investment in smallholder farmers can reduce vulnerability, it says here.

- An evaluation of the effectiveness of a direct payment for biodiversity conservation: The Bird Nest Protection Program in the Northern Plains of Cambodia. It works, if you get it right; now can we see some more for agricultural biodiversity?

- Finger millet: the contribution of vernacular names towards its prehistory. You wouldn’t believe how many different names there are, or how they illuminate its spread.

- Genome-Wide Association Studies. How to do them. You need a platform with that?

- Revisiting the sequencing of the first tree genome: Populus trichocarpa. Why to do them.

- Exogenous plant MIR168a specifically targets mammalian LDLRAP1: evidence of cross-kingdom regulation by microRNA. “…exogenous plant miRNAs in food can regulate the expression of target genes in mammals.” Nuff said. We just don’t understand how this regulation business works, do we.

- Anatomical enablers and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in grasses. It’s the size of the vascular bundle sheath, stupid!

- Land administration for food security: A research synthesis. Administration meaning registration, basically. Can be good for smallholders, via securing tenure, at least in theory. Governments like it for other reasons, of course. However you slice it, though, the GIS jockeys need to get out more.

- Genetic Analysis of Visually Scored Orange Kernel Color in Maize. It’s better than yellow.

- Comment on “Ecological engineers ahead of their time: The functioning of pre-Columbian raised-field agriculture and its potential contributions to sustainability today” by Dephine Renard et al. Back to the future. Not.

- Environmental stratifications as the basis for national, European and global ecological monitoring. Bet it wouldn’t take much to apply it to agroecosystems for agrobiodiversity monitoring.

- Use of Contingent Valuation to Assess Farmer Preference for On-farm Conservation of Minor Millets: Case from South India. Fancy maths suggests farmers willing to receive money to grow crops.

- Wild food plant use in 21st century Europe: the disappearance of old traditions and the search for new cuisines involving wild edibles. The future is Noma.

- Population genomic and genome-wide association studies of agroclimatic traits in sorghum. Structuring by morphological race, and geography within races. Domestication genes confirmed. Promise of food for all held out.

- Response of Sorghum to Abiotic Stresses: A Review. Ok, it could be kinda bad, but now we have the above, don’t we.

- Genetic resources: the basis for sustainable and competitive plant breeding. In Brazil, that is.

- A nuclear phylogenetic analysis: SNPs, indels and SSRs deliver new insights into the relationships in the ‘true citrus fruit trees’ group (Citrinae, Rutaceae) and the origin of cultivated species. SNPs better than SSRs in telling taxa apart. Results consistent with taxonomic subdivisions and geographic origin of taxa. Some biochemical pathway and salt resistance genes showing positive selection. No doubt this will soon lead to tasty, nutritious varieties that can grow on beaches.

Banter about cucurbits

Mary Beard, classics professor at Cambridge and effective general-purpose public intellectual, knows how to get your attention:

Sikyonians … were a sort of Greek footwear, but also a famous variety of cucumber and so a comic term for a phallus, and the ‘scarlets’ are a suspicious match for the scarlet dildo…

That’s from a review, enticingly entitled Banter about Dildoes, 1 of a book on Roman shopping with a much more boring title. 2 Well, I defer to Prof. Beard on Greek footwear and Roman sex toys, but I’m not so sure about that cucumber.

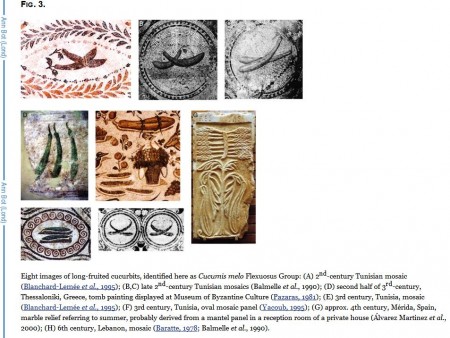

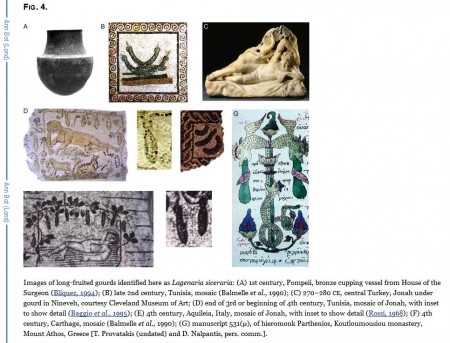

To see why, let’s turn to a 2007 Annals of Botany paper The Cucurbits of Mediterranean Antiquity: Identification of Taxa from Ancient Images and Descriptions, by Jules Janick et al.:

Many of the Renaissance botanists identified the cultivated sikyos of the Greeks as cucumber. Observers of more recent times, including de Candolle (1886), Sturtevant (Hedrick, 1919) and Hyams (1971), have concurred. However, as de Candolle (1886) admitted, the origin of cucumbers is the foothills of the Himalayas. Although Roberts (2001) identified two ancient mosaic images as depicting cucumber (see Figs 3E and and 4B) the former is clearly Cucumis melo, as evidenced by the longitudinal split in the fruit, and the latter is Lagenaria siceraria, as evidenced by the obviously swollen peduncular ends of the fruits. Archaeobotanical records include findings of several seeds purportedly of cucumber, but it is extremely difficult, even for experts, to differentiate between the seeds of C. sativus and C. melo (Bates and Robinson, 1995). Possibly, an identification of the species of these seeds could be accomplished by analysis of ancient DNA (Gyulai et al., 2006). In this survey of Mediterranean iconography and verbal sources of Roman times, we have found no hard evidence of the presence of cucumbers. There is some linguistic evidence that they became known in the region during the early Middle Ages (Amar, 2000) but the earliest European image known to us of what can be unquestionably identified as cucumber is from approx. 1335, post-dating the Mongol invasions. Renaissance depictions of cucumbers, although very common, show much less variation than do those of melons, which is suggestive of their being more recently introduced or of their lesser culinary appreciation or economic importance.

I think it is worth reproducing those mosaic images. Hopefully Annals of Botany won’t mind. Here’s 3E, the slitty Cucumis melo.

And here’s 4B, the knobby Lagenaria.

So, one can understand the mistake, but, pace Prof. Beard, that “famous variety of cucumber” was probably a famous variety of something else, either a muskmelon 3 or a bottle gourd. Though, as you can see from the illustrations, 4 that wouldn’t affect its comic potential. On the contrary…

PS Incidentally, since we’re talking funny-shaped cucurbits in history…

Nibbles: Mashua info, Veggies programme, Rice research, Genomes!, Indian malnutrition, Forest map, British agrobiodiversity hero, GMO “debate”, Lactose tolerance, Beer

- New Year Resolution No. 1: Take the mashua survey.

- New Year Resolution No. 2: Give the Food Programme a break, it can be not bad. As in the case of the recent episode featuring Irish Seed Savers and the only uniquely British veg.

- New Year Resolution No. 3: Learn to appreciate hour-plus talks by CG Centre DGs. And other publicity stunts…

- New Year Resolution No. 4: Give a damn about the next genome. Well, actually…

- New Year Resolution No. 5: Try to understand what people think may be going on with malnutrition in India. If anything.

- New Year Resolution No. 6: Marvel at new maps without fretting about how difficult to use they may be.

- New Year Resolution No. 7: Do not snigger at the British honours system.

- New Year Resolution No. 8: Disengage from the whole are-GMOs-good-or-bad? thing. It’s the wrong question, and nobody is listening anyhow.

- New Year Resolution No. 9: Ignore the next lactose tolerance evolution story. They’re all the same.

- New Year Resolution No. 10: Stop obsessing about beer. But not yet. No, not yet.

- Happy 2013!