Our friends at Bioversity have meta-done it again. After a milestone contribution a few years ago on the patterns of landrace diversity in farmers’ fields, now arrives a monumental review of the kinds of things that can be done to keep it there. ((Jarvis, D., Hodgkin, T., Sthapit, B., Fadda, C., & Lopez-Noriega, I. (2011). An Heuristic Framework for Identifying Multiple Ways of Supporting the Conservation and Use of Traditional Crop Varieties within the Agricultural Production System Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 30 (1), 125-176 DOI: 10.1080/07352689.2011.554358)) It comes as part of a special issue of Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences entitled “Towards a More Sustainable Agriculture.”

Our friends at Bioversity have meta-done it again. After a milestone contribution a few years ago on the patterns of landrace diversity in farmers’ fields, now arrives a monumental review of the kinds of things that can be done to keep it there. ((Jarvis, D., Hodgkin, T., Sthapit, B., Fadda, C., & Lopez-Noriega, I. (2011). An Heuristic Framework for Identifying Multiple Ways of Supporting the Conservation and Use of Traditional Crop Varieties within the Agricultural Production System Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 30 (1), 125-176 DOI: 10.1080/07352689.2011.554358)) It comes as part of a special issue of Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences entitled “Towards a More Sustainable Agriculture.”

It’s a long and complex article and impossible to do full justice to here, but the motivation behind it is simple enough: “to understand better the nature and contribution of traditional varieties to the production strategies of rural communities … and the ways in which they are maintained and managed.” That landraces still make such a contribution, despite expectations to the contrary in many quarters, ((Not least much of the rest of the CG system, one is tempted to say.)) is undeniable. As the authors admit, there is a lively ongoing debate about whether this can, or indeed should, continue. The superior adaptation of landraces to marginal conditions, the stability of their performance over time, the socio-economic conditions of small-scale farmers, and growing concerns about reducing agriculture’s dependence on inputs would all seem to point to a continuing, significant role in livelihoods strategies, at least in specific situations. But if so, why do they need help, as the authors also concede?

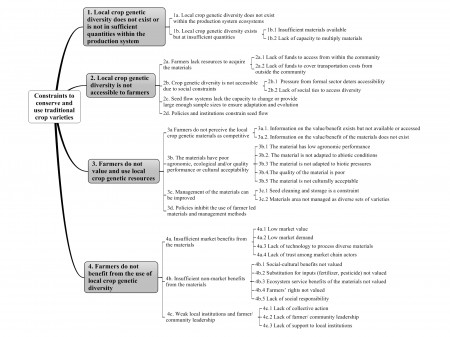

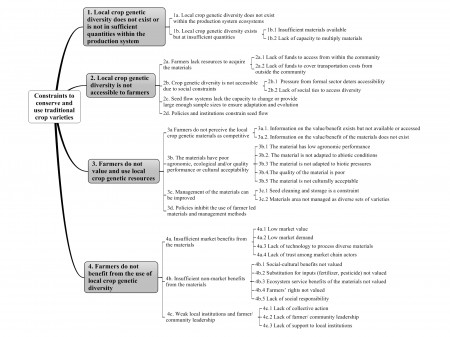

The problem is that lots of external factors work against landraces being all they can be, from dysfunctional seed systems to short-termist government policies. The diagram in Fig. 1 makes this clear (clearer still if you click on it):

The paper is really about what can be done to make it a more even playing field for landraces, by overcoming these multitudinous constraints. To that end its centrepiece, Table 1, is a huge list of the sorts of specific actions that have been undertaken around the world over the years in support of landrace management on farm.

So, for example, re-introducing landraces from a genebank (be it international or community), based on local adaptation and farmer preferences, would address constraints 1a and 2a, which have to do with the lack of sufficient planting material. Getting breeding programmes to use more landraces and farmer selections would be great for 2d, 3a, 3b, 3c, 3d, 4a, 4b and 4c (which incidentally seems pretty good value for money). Enabling farmer groups to develop a marketing strategy for landrace products would take care of 3a, 4a and 4c. And so on, and on, for 16 pages. The list of potential interventions is nothing if not exhaustive, and each is in turn exhaustively documented with references.

This is, like the previous review, a tour-de-force. If anything is missing from the discussion, it is perhaps a sense of what the best bets might be. That is, having identified a particular constraint or set of constraints, what are the things that are likely to be most effective in different contexts, for different crops? For that, a rearrangement of Table 1 summarizing and prioritizing interventions for each constraint would have been a useful start. Thus, if you find specific constraint X, you can do A, B and C, and B is what has worked best in the past in similar situations. Another area that could have been explored in more detail is how interventions work — or fail to work — when implemented together. But all this would be no more that tinkering with the masses of data that have been put together, which is perhaps already going on in Bioversity’s Maccarese eyrie.

The next major analytical step, surely, is to work out, or document if the information is already available, what these interventions actually cost. That would allow some calculation of possible returns on investment. Whether, and to what extent, any of the things that are so comprehensively described in this paper are ever done on a large scale in support of landrace conservation and use on farm will probably in the end be down to that. After all, those pushing the “alternatives” have already done their sums.

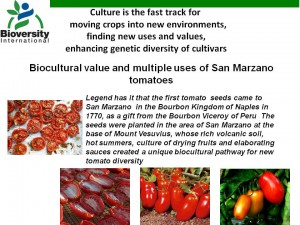

Our friend, colleague and, apparently, occasional reader Pablo Eyzaguirre, an anthropologist at Bioversity International, by all accounts gave a barnstorming performance in an internal seminar recently, but alas all that is available of it at the moment for those of us who were not there is his PowerPoint presentation, whose title we have stolen for this post. That is, of course, better than nothing, and I’m certainly not complaining. ((Or not much. Ed.))

Our friend, colleague and, apparently, occasional reader Pablo Eyzaguirre, an anthropologist at Bioversity International, by all accounts gave a barnstorming performance in an internal seminar recently, but alas all that is available of it at the moment for those of us who were not there is his PowerPoint presentation, whose title we have stolen for this post. That is, of course, better than nothing, and I’m certainly not complaining. ((Or not much. Ed.))

A while back we blogged a couple of times about

A while back we blogged a couple of times about