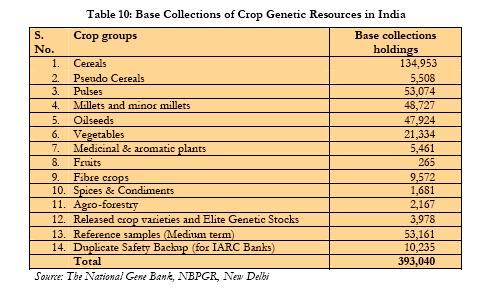

Yes, it’s out. India’s NBAP is online. Unfortunately, the pdf cannot be searched, for some reason, but a quick skim reveals that it does include significant consideration of agricultural biodiversity issues. For example, there’s a discussion of the role of the National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (NBPGR) in ex situ conservation of crop genetic resources.

Here’s the money quote, on page 52:

Traditional Indian farming systems are characterized by remarkable diversity owing largely to wide spectrum of agro-climatic situations and indigenous cultivars and native breeds adapted to specific local conditions. Notable efforts to collect crop diversity and documenting of livestock breeds notwithstanding, there is a need for on-farm conservation providing appropriate incentives. Ex situ conservation is expected to provide a strong backup to the efforts to facilitate access and meet unforeseen natural calamities. While there is an increasing coherence of policies and programmes on in situ, on farm and ex situ conservation, there is need to further strengthen these efforts.

The recommendations follow on pages 59-60. With regard to on-farm conservation, they are:

- Identify hotspots of agro-biodiversity under different agro-ecozones and cropping systems and promote on-farm conservation.

- Provide economically feasible and socially acceptable incentives such as value addition and direct market access in the face of replacement by other economically remunerative cultivars.

- Develop appropriate models for on-farm conservation of livestock herds maintained by different institutions and local communities.

- Develop mutually supportive linkages between in situ, on-farm and ex situ conservation programmes.

And, on ex situ conservation:

- Promote ex situ conservation of rare, endangered, endemic and insufficiently known floristic and faunal components of natural habitats, through appropriate institutionalization and human resource capacity building. For example, pay immediate attention to conservation and multiplication of rare, endangered and endemic tree species through institutions such as Institute of Forest Genetics and Tree Breeding.

- Focus on conservation of genetic diversity (in situ, ex situ, in vitro) of

cultivated plants, domesticated animals and their wild relatives to support breeding programmes. - Strengthen national ex situ conservation system for crop and livestock diversity, including poultry, linking national gene banks, clonal repositories and field collections maintained by different research centres and universities.

- Develop cost effective and situation specific technologies for medium and long term storage of seed samples collected by different institutions and organizations.

- Undertake DNA profiling for assessment of genetic diversity in rare, endangered and endemic species to assist in developing their conservation programmes.

- Develop a unified national database covering all ex situ conservation sites.

- Consolidate, augment and strengthen the network of zoos, aquaria, etc., for ex situ conservation.

- Develop networking of botanic gardens and consider establishing a ‘Central Authority for Botanic Gardens’ to secure their better management on the lines of Central Zoo Authority.

- Provide for training of personnel and mobilize financial resources to strengthen captive breeding projects for endangered species of wild animals.

- Strengthen basic research on reproduction biology of rare, endangered and endemic species to support reintroduction programmes.

- Encourage cultivation of plants of economic value presently gathered from their natural populations to prevent their decline.

- Promote inter-sectoral linkages and synergies to develop and realize full economic potential of ex situ conserved materials in crop and livestock improvement programmes.

Lots of sensible stuff, and it’s good to see agrobiodiversity in there at all. I was particularly interested in the recommendation to establish a national database bringing together all genebanks. Let’s see what happens, maybe it’s a small step out of genebank database hell. No mention of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, though.

LATER: Yes, indeed, the ITPGRFA is mentioned on p. 90. Thanks, Eliseu. Sorry about that. Still trying to work out why I can’t search the pdf… Ah, can’t search online, but can if I download it first.

LATER STILL: Forgot to mention that there are also a number of references to crop wild relatives, check out Table 4, for example.