An article in PLoS Biology recently suggested that IUCN should change the classification system it uses for protected areas (PAs). 1 Currently reflecting management intent (e.g. “National Park: managed mainly for ecosystem protection and recreation”), the idea would be for the new categories to rather “be based on the quality and quantity of the contribution of each PA to conservation of biodiversity (and associated sociocultural values).” So: actual result, rather than intent; and “what ” and “how much” rather than “how.” Seems like a pretty good idea. And it also seems like the concept could be applied not just to protected areas, but to conservation actions in general. That would spell the doom of the tired old in situ/ex situ dichotomy. Not a minute too soon, as far as I’m concerned.

African protected areas surveyed

The EU-funded “Assessment of African Protected Areas” is out:

The purpose of the work is to provide to decision makers a regularly updated tool to assess the state of Africa PAs and to prioritize them according to biodiversity values and threats so as to support decision making and fund allocation processes.

It is great stuff: detailed, standardized descriptions of the importance of — and threats faced by — each protected area in Africa. I wonder if something similar will ever be done for agricultural biodiversity. An interesting first step might be to mash these results with those of the recent survey of crop wild relatives in protected areas. Unfortunately, the agrobiodiversity and protected areas communities hardly ever speak to each other.

Nibbles: Anti-diversification, chickens, bananas, registers, tropical fruits

- US subsidy system prevents diversification. Via.

- Chicken domestication; possibly more than you could ever want to know.

- Red bananas; Raul unavailable for comment.

- Filipino community registers agrobiodiversity.

- Tropical fruit diversity conserved, studied and consumed in the US. That includes the citron. 2

Weekly helping of potatoes

The Economist seems to have a thing about potatoes this week. There’s a story about how Peru is trying to cash in on its spud heritage. (Note to editor: the olluco is not a type of potato.) There’s a book review, of John Reader’s Propitious Esculent. And there’s even an editorial explaining how the humble tuber is at the root — as it were — of globalization. The International Year of the Potato cannot be over too quickly.

A modest proposal

That last but one post of Jeremy’s got me thinking. How do we find out if Arachis ipaensis is still at that locality? I mean, short of mounting a fully-fledged expedition of groundnut experts at vast expense, that is. One way might be to ask a local person to check for us. Ok, a wild peanut species might not be the best thing to try this with, but you get the idea. Problem is, how do we identify a local person who knows that area?

Then I remembered something Jeremy sent me recently. WikiLoc is a website to which you can upload your favourite walk or cycle ride as a GPS track. You can then view all these in a number of different ways, including in Google Earth. So I gbiffed (sensu Cherfas, 2008) the localities of wild Arachis species and viewed them in Google Earth together with all the tracks from South America available on WikiLoc.

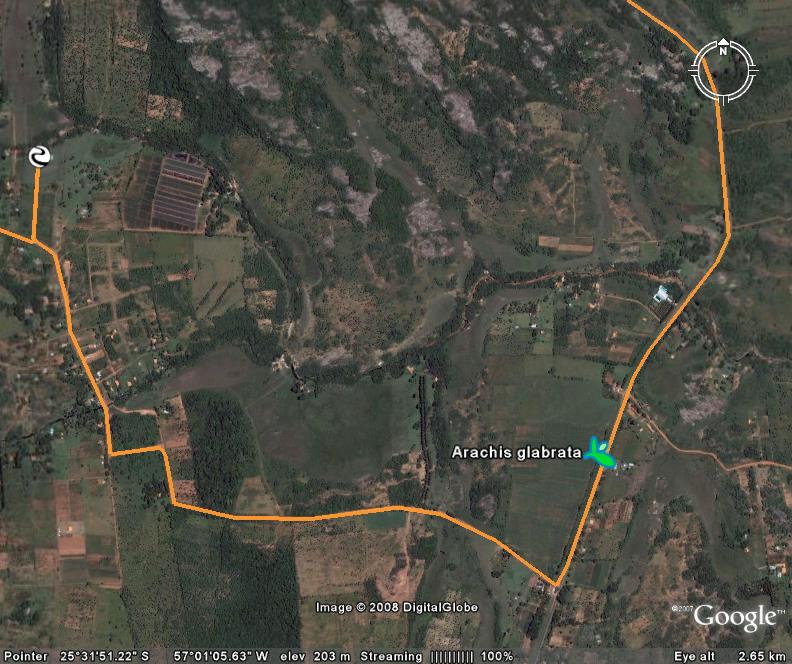

Well, of course, none of the trails was anywhere near the locality of A. ipaensis. But I did find others that came near — or very near — the localities of other species. Check this one out, for example:

It’s a 32 km circuit around Piribebuy in Paraguay, and it was uploaded by someone called Yagua. It takes about 4 hours to walk it. And it so happens that a specimen of Arachis glabrata was collected along Yagua’s favourite trail, around its southeastern corner:

Now, I don’t think A. glabrata is a particularly significant component of the groundnut genepool, but say, for the sake of argument, that it had been. Couldn’t we ask Yagua to keep an eye on it for us? Multiply by the more than 10,000 tracks on WikiLoc and pretty soon you’re talking about a real global network of agrobiodiversity monitors. But maybe we should test the idea out with a somewhat more — ahem — charismatic plant. And imagine if germplasm collectors start adding their tracks to WikiLoc.