- NY Botanical Garden launches summer Edible Garden celebration.

- Thingy for getting more syrup out of maples invented.

- Farmer floods his fields on purpose.

- Insights into tomato late-blight resistance. Do try and keep up!

- A very English guerrilla gardener.

- Pictures of weird fruits and vegetables.

- Russian starters. Uhm, I spot a trend.

- The future of aquaculture: giant robotic roaming cages.

- Saving California’s Sebastopol Gravenstein apple.

- “Zeytinburnu Medicinal Plant Garden, opened in 2005, is Turkey’s first and only medicinal plant garden.”

- Something else has it in for bees: Chinese hornets.

Bolivians going back to their roots

I blogged a couple years ago about what might be called the “1491 controversy,” which hinges on whether you think the Amazon and adjacent areas were densely populated and closely managed before Columbus arrived, or an unproductive, largely pristine wilderness. One of the areas in question is the basin of the Beni River in Bolivia. Whatever your stand on the 1491 debate, it is undeniable that the Beni is a heavily modified landscape.

Shallow floodwaters cover much of the low-lying lands in the Llanos de Moxos during part of the rainy season. The rest of the year, dry conditions prevail and water is scarce. The alternation between seasonal flooding and seasonal drought, combined with poor soil conditions and lack of drainage, make farming in these areas difficult. The ancient inhabitants of the area created an agricultural landscape to solve these problems and make the area highly productive. They constructed a system of raised fields, or large planting surfaces of earth elevated above the seasonally flooded savannas and wetlands. Experiments have shown that the raised fields improve soil conditions and provide localized drainage and the means for water management, nutrient production, and organic recycling.

Well, Bolivian researchers are now suggesting that farmers return to these “camellones,” or raised fields, to harness the seasonal flooding, rather than succumbing to its depredatioons. Oxfam is supporting the project. The BBC was there.

If, as predicted by many experts, the cycles of El Niño/La Niña are going to increase in intensity and frequency, then the project has the capacity to help poor families cope better with the extreme weather events and unpredictable rainfall that are to come.

It would also allow them to cut down on fertilizers, and dabble in aquaculture. There is some scepticism, which has to do with the necessary investment in time and effort. But early results show gains in productivity, apparently, although it’s unclear from the BBC article what exactly is being compared. Anyway, there is much optimism.

This process could be repeated in various parts of the world with similar conditions to the Beni like parts of Bangladesh, India and China.

In the words of local farmer Maira Salas: “We are only just now learning how our ancestors lived and survived.” Well, yes, but with a difference. Some of the crops that are been grown in the camellones are exotic, which is fine, of course. But will there also be a revival of neglected traditional indigenous crops?

Nibbles: Seed travels, Carotenoids in cucumbers, Tea and hibiscus, Sea level rise, Tewolde on climate change, SPGRC

- After a year’s travel in search of seeds, Adam Forbes turns in his report.

- The genetics of orange-fleshed cucumbers elucidated.

- Tea and hibiscus booze.

- Video of honey harvesting.

- Maps of sea level rise. All somewhat unsatisfying, somehow.

- “Because we are poor, we shall suffer first but, ultimately, we shall all die together.”

- SADC Plant Genetic Resources Centre (SPGRC) director Paul Munyenyembe does the public awareness thing.

Nibbles: Cacao, Soil mapping, Rice terraces, Maize, Cereus

- “USDA’s Bourlaug International Science Fellows Program has partnered with non-profit and for-profit organizations to identify new agricultural techniques for cocoa cultivation and to control cocoa diseases.” And do some conservation and breeding, surely.

- Big shots call for a decent global digital soil map. Seconded.

- Cool photos of rice agricultural landscapes.

- Roasting maize, Mexico style. Oh yeah, there’s also a nifty new maize mapping population out.

- Peruvian apple cactus doing just fine in Israel.

Old maps used to track down hops in Sweden

![]() I’ve done a fair amount of reading and thinking about the theory and practice of germplasm collecting in my time, but I don’t think I’ve ever come across an example similar to the one described in a recent paper in Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. ((Strese, E., Karsvall, O., & Tollin, C. (2009). Inventory methods for finding historically cultivated hop (Humulus lupulus L.) in Sweden. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. DOI: 10.1007/s10722-009-9464-9.))

I’ve done a fair amount of reading and thinking about the theory and practice of germplasm collecting in my time, but I don’t think I’ve ever come across an example similar to the one described in a recent paper in Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. ((Strese, E., Karsvall, O., & Tollin, C. (2009). Inventory methods for finding historically cultivated hop (Humulus lupulus L.) in Sweden. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. DOI: 10.1007/s10722-009-9464-9.))

In it, Swedish researchers describe how they took advantage of a couple of interesting quirks in the history of Sweden to devise what I think is a pretty novel strategy for sampling agrobiodiversity. They were interested in collecting germplasm of hops (Humulus lupulus) for a new genebank that’s under development. Now, the thing is that, although this crop is no longer grown in Sweden now, for 400 years from 1442 doing so was compulsory, in order to guarantee sufficient domestic production for beer-making. Very sensible, too.

Initially, all peasants were required to grow at least 40 hop poles. By 1483, the quantity was increased to 200 hop poles. The law was not formally repealed until 1860. As a result of this law, the plant has left several financial, fiscal and legal imprints on Swedish history.

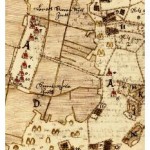

The second historical curiosity about Sweden is that it boasts a unique set of some 12,000 large-scale maps dating back to the mid-17th century. Because of the hops law, hop gardens are actually marked on these maps in some detail (click to enlarge).

So the collectors used what they call a “history to plant” method to identify likely areas for collecting, using not only maps such as the one reproduced above, but also…

…medieval charters from the fifteenth century files of land belonging to the abbey of Vadstena, documents from the expeditions of Carl von Linné and his pupils from the eighteenth century and also documents from the breeding program in Svalöf from the beginning of the twentieth century.

And a pretty successful strategy it was too.

We found no hop plants at locations which were not indicated in the maps as hop gardens. Today living plants were possible to find in more then 33% of the total inventoried sites, indicated as hop gardens on large-scale maps.

As I say, I can’t think of another example of the use of historical maps to locate specific crops for sampling. No doubt the specific circumstances that made this possible in Sweden are not all that common around the world. Anyway, if you know of similar work, let me know. Always interested in keeping up to date with the latest in germplasm collecting.