- Faidherbia albida gets another push. To quote from the recent Crops for the Future dissection of neglected/underutilized species: if it’s so good, how come it’s not used more?

- The Indo-European roots of names for pulse crops. Not nearly as boring as it sounds. Oh, and since we’re on the subject…

- Human biodiversity files: athleticism, foodism.

- Huge EU project monitors pollinators. What could possibly go wrong?

- Cleaning up DNA Sequence Database Hell.

- Nice biodiversity hotspot maps. No plants. Definitely no agrobiodiversity.

- A philosopher’s take on that organic agriculture meta-analysis.

- Not Musa, but still edible.

Nibbles: Heirloom conference, Saving plants, Aquaculture benefits, Ancient Egyptian botany, Coffee blogs, ITPGRFA, GIAH

- National Heirloom Exposition coming up. Any of our readers going? Oh come on, one of our readers must be going!

- Kew head honcho calls for a botanical New Deal.

- WorldFish head honcho calls for an aquacultural New Deal.

- A papyrus of recent botanical literature on ancient Egypt.

- Coffee blogs to follow. Oh gosh, am I blushing?

- Participants “gain more knowledge” at policy workshop. Of the ITPGRFA, that would be.

- A couple of Chinese agricultural systems gain recognition as Globally Important Agricultural Heritage.

Organic farming: what is it good for?

Organic produce and meat typically is no better for you than conventional food when it comes to vitamin and nutrient content, although it does generally reduce exposure to pesticides and antibiotic-resistant bacteria, according to a US study.

Organic farming is generally good for wildlife but does not necessarily have lower overall environmental impacts than conventional farming, a new analysis led by Oxford University scientists has shown.

Time for a meta-meta-analysis?

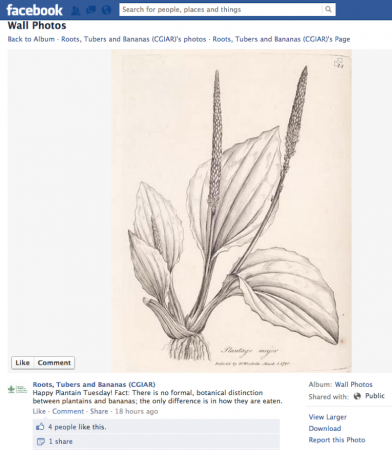

When is a plantain not a plantain?

Corner a Musa-wallah over a pint of sorghum brew, and ask them to tell you the difference between a banana and a plantain. Seven will get you eleven you’ll be no wiser when they eventually finish frothing. So turn instead to the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Banana’s Facebook page, for true enlightenment.

Yesterday, you see, was Plantain Tuesday. So what do we learn?

That’s right! 1 “There is in fact no formal, botanical distinction between plantains and bananas; the only difference is in how they are eaten”. So stick that in your cooking bananas, Dr Musa-wallah.

And there’s more.

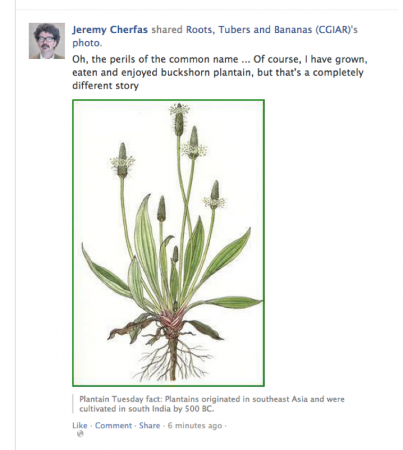

“Plantains originated in southeast Asia and were cultivated in south India by 500 BC”. Triffic. What about bananas, then?

Hang on, though, I know what you’re thinking. Those two pictures don’t look much like any bananas you’ve ever seen. And you would be right about that. But hey, it’s only Facebook. Who cares whether the information is accurate?

Nibbles: Bees, Gait genes, Eradicate hunger, Conference

- Honeybees create a buzz in Nepal.

- Gene for silly equine walks.

- Men and Women Farming Together Can Eradicate Hunger. Headline says it all, really.

- We’re not the only ones wondering what’s going on at the 2nd global conference on agriculture, food security and climate change, which started yesterday.