The 25th anniversary special issue of the Indian Journal of Plant Genetic Resources (IJPGR) is available by permission from the Bioversity International website. Though this is subject to some restrictions on re-use, it is nevertheless pretty cool.

Sonalika searching

A blog post from CIMMYT presented a welcome opportunity to play around with a range of online information resources on wheat varieties, despite the fact that some of the links are broken.

So let’s say I want to find out about a particular variety. Sonalika, for example. I heard about it as being an important older Indian variety, and want to find out more: a pedigree, maybe some performance data, maybe even get some seed. First, I headed on over to the IWIS-Bib database, which “is a supplement to the International Wheat Information System. Each record in IWIS-Bib identifies a publication, and each publication describes a cultivar.” For Sonalika, that returns the citations of 11 references. Good start, though I do now have to get hold of the publications themselves. Maybe in the future I’ll be able to download a PDF, or there will be a link to Google Scholar, or whatever.

Let’s move on. I was not able to find a way of getting performance data for Sonalika from IWIS proper, though I was at the time pretty sure I’d be able to order seed of it from CIMMYT. But, having thought that, I then checked, and Sonalika does not feature in a Genesys search as being conserved at CIMMYT, although you get hits from various other genebanks, including USDA. And there’s plenty of characterization and evaluation data there. I may be doing CIMMYT a disservice here, though. Maybe I didn’t look hard enough, but certainly there was no way of getting easily from a bibliographic hit on a particular variety to evaluation data on it. Which it would be nice to be able to do.

Moving on again, I then headed over to the Genetic Resources Information and Analytical System for Wheat and Triticale (GRIS), the main subject of the blog post I mentioned at the beginning. Entering Sonalika in the little search box gave me a whole lot of very cool stuff. Like a pedigree: II-53-388/ANDES//(SIB)PITIC-62/3/LERMA-ROJO-64. Which you might like to compare with the one on GRIN: II53-388/Andes//Pitic 62 sib/3/Lerma Rojo 64. Reassuringly similar. And accession numbers; which interestingly do not include CIMMYT. So it does look like I wouldn’t be able to get Sonalika from them after all. You also get summary evaluation data and even recommendations for use, which is very handy. And a pedigree diagram, which is, however, frustratingly impossible to export.

So, overall, a not uninteresting though ultimately somewhat disappointing experience, mainly because of the necessity of hopping between websites. But maybe those linkages will come now that a bunch of the people concerned have had a meeting, as described in the post that started all this. Fingers crossed.

Nibbles: Coconut origins, Microbe genebank, Stay-green barley, Sachs may suck, Cap in hand, Wheat information, IITA birthday, Cat art, Poppy biosynthesis, Correcting names

- Coconut origins, the quick version.

- Chile gets a bugbank.

- Stay-green barley genes located. In a genebank collection, natch. What now, a Stay-green Revolution?

- New Economist blog agnostic about Millennium Villages.

- Plant scientists call for $100 billion investment in, er, plant science.

- Wheat pedigrees online.

- IITA a youthful 45.

- Cats in Islam.

- Noscapine production in poppies is complex, but not so complex that boffins can’t figure it out.

- Want help in getting taxonomic names right? What you need is the Taxonomic Name Resolution Service. Does that mean we don’t need this any more?

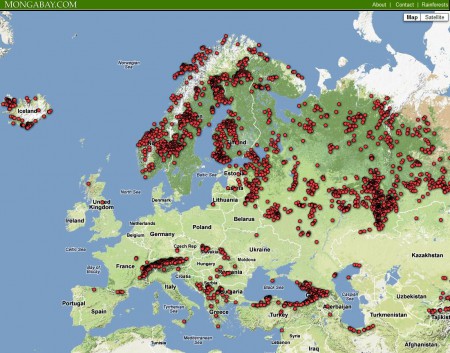

Global system for monitoring vegetation disturbance launched

The redoubtable Mongabay.com has just announced the beta version of the Global Forest Disturbance Alert System (GloF-DAS). How it works is that four times a year (at the end of March, June, September and December) the CASA ecosystem modeling team at the NASA Ames Research Center produce something called the “Quarterly Indicator of Cover Change” (QUICC). This compares global vegetation index images from NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) from exactly a year before with the ones they just got. GloF-DAS then takes the QUICC data and maps the location of forest disturbance as the center points of 5×5 km areas where there was a >40% loss of forest greenness cover over the previous 12 months.

Here’s the result for Europe, for the year period ending March 2012.

There’s some issue I’d take with this approach. Most importantly, comparing March with March is not necessarily comparing vegetation at the same level of seasonal development in the temperate zone. But I think this is a great step forward in developing a global system for monitoring threats of genetic erosion. As the developers point out:

The cause(s) of any forest disturbance point detected in this map has yet to be confirmed.

Disturbance locations and impacts are subject to verification through local observations.

So imagine a next iteration of the system where local observers can annotate some of those potential disturbance points. A bit like what happens in the National Phenology Network in the USA, though for a different purpose. 1 And information will flow out more freely too.

In coming months, GloF-DAS will offer an alert system whereby users can sign up to get notifications via email or SMS text message on recent changes in forest cover for a specified location or country.

Of course, for this to be truly a game-changer we who are interested in monitoring threats to crop wild relatives, say, would need the ability to combine the potential threat data of GloF-DAS with our own data on species occurrence or diversity. It doesn’t look to me like that’s possible just now, but perhaps it is something that we as a community can suggest to the developers.

Nibbles: GIBF, Identifiers, Farming animals, Geomedicine, Seed saving, Seeds of Success, CWRs, CORA 2012, Sourdough culture bank, Phenology, Wild Coffea, Cassava conference, Condiments, Gulf truffles, Cashew nut, Home gardens, Tea, Bacterial diversity

- GIBF taxonomy is broken. We’re doomed. No, but it can be fixed. Phew.

- Maybe start with a unique identifier for taxonomists? Followed by one for genebank accessions… Yeah. Right.

- Domesticating animals won’t save them. And more on the commodification of wildlife. Is that even a word?

- Geomedicine is here. Can geonutrition be far behind? We’re going to need better maps, though.

- Saving heirlooms, one bright student at a time.

- “Botanists Make Much Use of Time.” If you can get beyond the title, there’s another, quite different, but again quite nice, seed saving story on page 3.

- “Why aren’t these plants the poster children [for plant conservation]?” You tell me.

- Or, instead of doing something about it, as above, we could have a week of Collective Rice Action 2012.

- You can park your sourdough here, sir.

- How Thoreau is helping boffins monitor phenology. But there’s another way too.

- “She drinks coffee. She farms coffee. She studies coffee.” Wild coffee.

- Massive meet on the Rambo Root. Very soon, in Uganda.

- Ketchup is from China? Riiiight. Whatever, who cares, we have the genome!

- And in other news, there are truffles in Qatar. But maybe not for long.

- The weirdness of cashews.

- The normalcy of home gardens as a source of food security — in Indonesia.

- Ok, then, the weirdness of oolong tea.

- Aha, gotcha, the normalcy of office bacterial floras! Eh? No, wait…