- Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin 44.

- How the Sheep Trust was born.

- Map of British gardeners.

Lost Crops of Africa on air

The National Research Council’s series on Lost Crops … is on our shelves, and well-thumbed too. Now comes news that Voice of America has just launched a five part series reporting on various aspects of the story. The first episode — “Lost Crops” of Africa Could Combat Poverty and Hunger — is online here, with links so you can download and listen to the broadcasts.

Other episodes available are:

- Certain Fruits Among Africa’s Lost Crops with Noel Vietmeyer

- Certain Vegetables Among Africa’s Lost Crops with Martin Price

- Local African grains among Lost Crops with Adi Damania

- Plans and Hopes for Developing Lost Crops of Africa with Professor Damania again

It’s odd, though, that in the final episode Professor Damania gives the impression that only two of the CGIAR centres are involved in research on these lost crops. We can think of others…

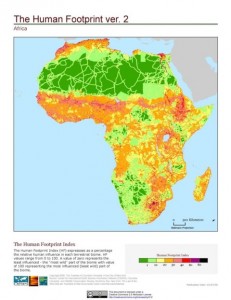

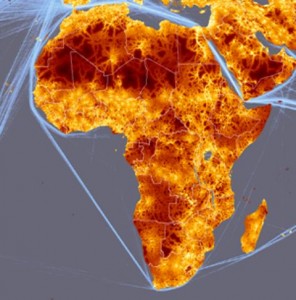

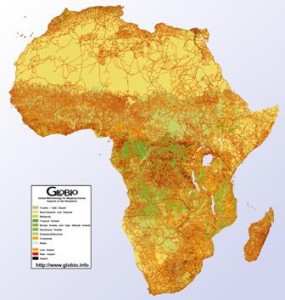

Three different ways of looking at Africa

I ran the Last of the Wild dataset I talked about yesterday past our friend Andy Nelson, he of the accessibility map, and his reaction was that there was a quick paper, or at least an MSc thesis, in comparing that map with his and with the product of the GLOBIO project. Well, here’s what Africa looks like according to the three different methodologies, just to give you a taste. Quite similar, at first look, though we’ll have to wait for that MSc to be sure, I guess. Now, the question is, can such data be used to predict things like the amount of agrobiodiversity in farmers’ fields?

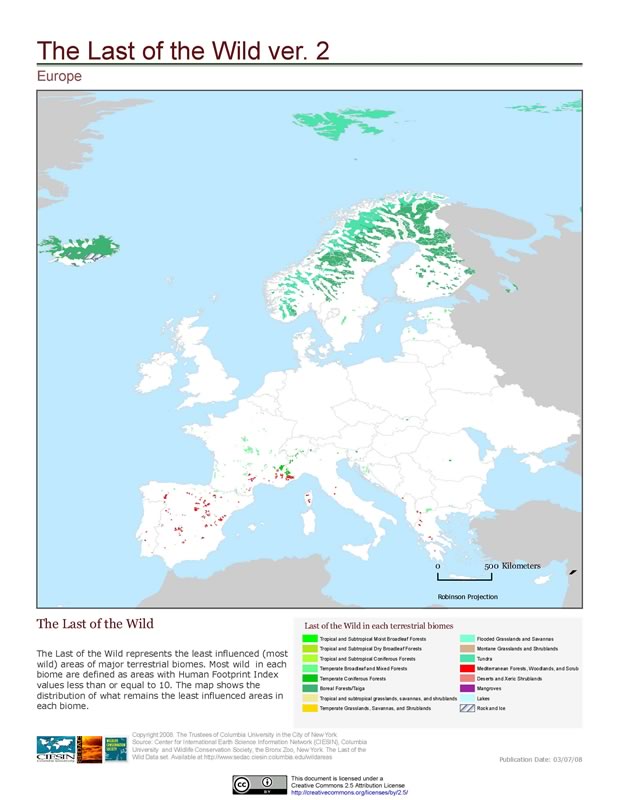

The call of the wild

Not sure how long they’ve been available, but I’ve just learned that the new versions of the Last of the Wild maps are out. The first version is a few years old now.

The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) at Columbia University have joined together to systematically map and measure the human influence on the Earth’s land surface today. The Last of The Wild, Version Two depicts human influence on terrestrial ecosystems using data sets compiled on or around 2000.

These are Europe’s most untouched areas:

Not much left. There are also global and continental maps of human footprint and human influence index, although I must say I haven’t fully digested the difference between the two. And you can download the data and play around with it yourself, of course. Let the mashing begin!

Documenting the history of fisheries

- Human fishing and impacts on near-shore and island marine life — including the catching of shellfish, finfish and other marine mammals — apparently began in many parts in the Middle Stone Age — 300,000 to 30,000 years ago — 10 times earlier than previously believed;

- Passages of Latin and Greek verse written in 2nd century CE suggest Romans began trawling with nets;

- In the early to mid 1800s, years of overfishing followed by extreme weather collapsed a European herring fishery. Then, the jellyfish that herring had preyed upon flourished, seriously altering the food web;

- In the mid 1800s, periwinkle snails and rockweed migrated from England to Nova Scotia on the rocks ships carried as ballast — the tip of an “invasion iceberg” of species brought to North America;

- In less than 40 years, Philippine seahorses plunged to just 10% of their original abundance, reckoned in part through fishers’ reports of each having caught up to 200 in a night in the early days of that fishery.

Just some of the insights that will be shared by participants in the forthcoming Oceans Past II conference, according to EurekaAlert. It sounds absolutely fascinating:

Using such diverse sources as old ship logs, literary texts, tax accounts, newly translated legal documents and even mounted trophies, Census [Census of Marine Life] researchers are piecing together images — some flickering, others in high definition — of fish of such sizes, abundance and distribution in ages past that they stagger modern imaginations.

It’s all part of the History of Marine Animal Populations (HMAP) project. One of the regions being studied is the Mediterranean, and the project website has some great historical photographs of fisheries, for example from the Venetian lagoon. The “scientific area” includes an erudite answer to the question “Did the Romans eat fish?” by HMAP leader of the Black Sea project Tonnes Bekker-Nielsen. Here’s a perhaps surprising snippet:

The fish product most likely to be found in the average Roman kitchen or cookshop was garum, a sauce made from fermented fish and similar to the sauce known as umami or nuac, which is very popular throughout East Asia today. Garum was used to give flavour to stews, soups and many other dishes; it could also be eaten as a relish on bread.

The project includes some interesting data visualization tools.