- Coffee rust is doing a number on livelihoods in Central America.

- Wheat blast could do the same in South America.

- ILRI DG on smallholder livestock producers: one-third don’t have the conditions in which to be viable, one-third can go either way and one–third can be successful. I suppose all of them are going to need adaptation options.

- Not to mention extension services.

- Meanwhile, bureaucrats busy protecting the Mediterranean diet.

- The inevitable productivity penalty of organic.”

- Douglas fir ready for its genomic closeup.

- Cryopreservation update, with video goodness.

- Lots of ways to skin the malnutrition cat: zinc and rice.

Giant White Cuzco Maize DOC

Peru has made further moves to protect a maize variety typical of Cuzco:

The Foreign Ministry reported that the designation of origin “Giant White Cuzco Maize” was protected by the Peruvian government in Chile, through its registration with the National Institute of Industrial Property (INAPI) of that country, which culminates a legal process started a few years ago and will adequately promote in the Chilean market one of our most representative agricultural products.

Four years ago the Peruvian government declared the variety part of the country’s cultural patrimony. It is being used by WIPO as a case study of the use of denomination of origin to revive communities. Giant White Cuzco Maize joins a whole series of other typical products “enjoying” denomination of origin protection in South America. 1 Though one does wonder to what extent this particular move was a reaction to the controversy between Peru and Chile over pisco.

Anyone willing to hazard a guess as to whether, and if so to what extent, this will affect exchange of germplasm of this maize variety for research and breeding? Will Amazon have to stop selling it?

Protecting apple images

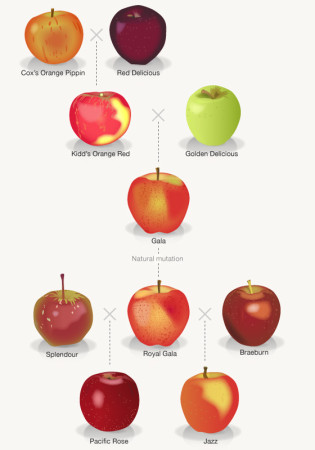

I really like this diagram of the family tree of the Jazz apple, A New Zealand-bred favourite.

Problem is, I may be breaking some sort of law reproducing it here. The website where I found it, Te Ara, or the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, says, at the bottom of each page, that:

All text licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand Licence unless otherwise stated. Commercial re-use may be allowed on request. All non-text content is subject to specific conditions. © Crown Copyright.

Well, I don’t really want to use the text, certainly not commercially, so that means specific conditions apply. What might they they?

This item has been provided for private study purposes (such as school projects, family and local history research) and any published reproduction (print or electronic) may infringe copyright law. It is the responsibility of the user of any material to obtain clearance from the copyright holder.

It also gives an indication of how to cite the item, which I am happy to do: Ross Galbreath. ‘Agricultural and horticultural research — Advances in plant science’, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 14-Nov-12 URL.

I left comments on the item on two occasions, asking for permission to use the image. No reply. I then emailed the general address provided on the About page. No reply. So, having waited a decent interval, I’m going for it. Let’s see what happens. I hope someone wanting permission to use the apple for breeding purposes finds it more straightforward than accessing the image in which it features.

How is yoghurt like a hybrid seed?

An audio recording of a 90-minute panel discussion is not something to tangle lightly with, not even when the topic is one of my favourites: fermentation. I finally got around to it, though, and I’m very glad I did.

The recording dates from exactly a year ago today, which I swear I didn’t know before writing this, and a discussion at the American Museum of Natural History as part of their series Adventures in the Global Kitchen. The Art of Fermentation featured Sandor Katz, who needs no introduction to fermentation heads, and Dan Felder, head of research and development at the Momofuku Culinary Lab. 2

I found it really fascinating even though – possibly because – I know a bit about fermentation. And one bit in particular joined fermentation to another interest: seeds and intellectual property rights. I know!

Starting at about 1 hr and 8 mins, Sandor Katz was explaining why, if you decide to do home-made yoghurt with most store-bought yoghurt as a starter, it is ok for the first generation or two but by three and four is pretty runny and not very good. He said that bulk industrial yoghurt depends on pure cultures of just two species of bacterium, Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. Local, heirloom yoghurts, if you will, contain those two as part of a larger ecosystem, and the ecosystem as a whole is able to defend itself from microbial interlopers, whereas the pure cultures are not. And that’s why an heirloom yoghurt can be renewed generation after generation without changing much in its properties.

Katz pointed out that greater control for the manufacturer means some benefits but less self-sufficiency for the consumer. You can buy their yoghurt, but you can’t use it to make your own. And he specifically likened that to the development of F1 hybrid seeds, which likewise offer benefits at the expense of self-sufficiency. Because you can’t save your own seeds from F1 hybrids.

Except, of course, that you can. You don’t get what you started off with, but that’s the point. With time and space and a little bit of knowledge you can dehybridise F1s, exploiting all the goodies that the breeders put in there and, who knows, coming up with something as good or better and being able to maintain that generation to generation. I have no idea whether you can do that with industrial yoghurt, exposing it to a bit more wild culture and selecting among mini-batches.

And that led to a not very satisfactory discussion of intellectual property rights as they relate to ferments and the kind of work Dan Felder is doing with Momofuku. “I can’t talk about that,” he said, disarmingly. But then he did, worrying that plagiarism was much more common than credit and attribution among chefs. And that’s why they keep some things secret.

Katz then pointed out that we owe all the ferments and most of the techniques in use today to generations of experimenters before us. Sound familiar?

Ferments and techniques, but not substrates, countered Felder, who makes a miso based on Sicilian pistachios, and much else besides. He was proud to accept that he was building on generations of experimentation and tradition. Just not writing it up on Twitter.

What’s up in seed laws?

The notion of farmers saving seed from one harvest to plant for the next is deeply ingrained, especially in ideas about subsistence and sustainable farming. Indeed, that process is usually seen as the foundation of all agriculture, to be abandoned at our peril. In the early 1990s, we saw attempts to shift the discussion on intellectual property from the farmer’s right to save seed of a formally-protected variety to the farmer’s privilege to do the same. Much of the rhetoric that attempts to stick it to The Seed Man focuses on seed saving, and the impact that F1 hybrids, GMOs and other evils will have on farmers who want to save their own seeds.

It is not surprising, therefor, that there’s a lot of sound and fury around the subject. From which melée I offer two snippets.

Bifurcated carrots is keeping a close eye on the progress of the proposed new European seed laws through the labyrinthine corridors of power. He’s hopeful that the lack of progress is a good thing, because it will start the whole process again.

While the seed industry thinks the proposal can be fixed with a few small changes, this is not the position of most seed related NGOs around Europe. It is certainly not our position. The current proposal is not without some good aspects, but overall it’s seriously flawed and should be rewritten.

James Ming Chen, a lawyer, will have no truck with any silly emotional, nostalgic idiocy.

Seed-saving advocates protest that compelling farmers to buy seed every season effectively subjects them to a form of serfdom. So be it. Intellectual property law concerns the progress of science and the useful arts. Collateral economic and social damage, in the form of affronts to the agrarian ego, is of no valid legal concern.

But would he actually prevent seed saving?