- Conserving dambos for livelihoods in southern Africa. How many CWRs are found in such wetland habitats around the world, I wonder.

- Cucumis not out of Africa.

- Exploring “the connection between traditional knowledge of herbs, edible and medicinal plants and media networked culture.” And why not.

- PBS video on malnutrition.

- Fungal exhibition at RBG Edinburgh.

- Indian Council on Agricultural Research framing guidelines for private-public partnerships in seed sector. That’ll stop the GM seed pirates.

- Conserve African humpless cattle! They’re needed for breeding.

- UG99 — and crop wild relatives — in the news. The proper news. The one people pay attention to.

- Vanilla lovers better start stocking up.

- Kenyan farmers earning money selling sorghum to brewers. What’s not to like.

Nibbles: Breeding, Art, Bison, Pumpkin seeds, Sweet potato, Bambara groundnut, Carnival

- Cary Fowler on the need to breed.

- MRIs of fruits and vegetables. Well, why not?

- The genetic consequences of bovine inter-specific sex explained. SFW.

- How Mrs Joséphine Enoce Bouanga makes milk from squash seeds in Pointe-Noire.

- Gates Foundation orange sweet potato project in Mozambique. Still waiting to hear what they’re going to do with all those useless landraces they’ll be replacing.

- Nourishing the Future does Lost Crops of Africa 101. Beginners, start there, but don’t expect to be taken anywhere interesting.

- Blog carnival Scientia Pro Publica #35 is up, but what’s with the verse alphabetical order? Harummph.

The horse in Mongolian culture

They may be trying to develop and diversify their agriculture now (well, since the 1950s), but Mongolians are traditionally very much a nomadic herding culture, with the horse at its centre. 1 One expression of that is how early kids learn to ride.

They may be trying to develop and diversify their agriculture now (well, since the 1950s), but Mongolians are traditionally very much a nomadic herding culture, with the horse at its centre. 1 One expression of that is how early kids learn to ride.

Most young Mongolians — boys in particular — learn to ride from a very young age. They will then help their fathers with the herding of goats, sheep and horses. Some children have a chance to ride at festivals called Naadam — the biggest of which is held on 11th-13th July in Ulaanbaatar — though there are naadams held throughout the year all over the countryside. Young jockeys between the age of 5 and 12 (girls and boys) race horses over distances ranging from 15km to 30km. There are 6 categories for the races depending on the horses’ age, including a category for 1 year old horses (daag) and one for stallions (azarag).

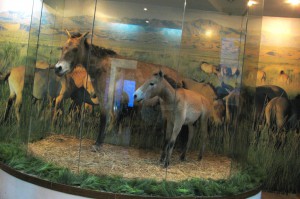

Alas, this museum display is as close as I got to seeing the famous Mongolian Wild Horse or Przewalski’s Horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), locally known as takhi.

It’s possibly the “closest living wild relative of the domesticated horse, Equus caballus.” Certainly it is genetically very close to the local domesticated breed based on molecular markers, though that could be because of interbreeding. Last seen in the wild in 1969, its restoration in China and Mongolia from captive stock, for example to the Hustain Nuruu National Conservation Park, is one of the great conservation success stories.

Livestock reverse desertification

There’s something delicious about received wisdom being overturned. For example, you’ll hear it said, categorically, that livestock turn fragile landscapes into desert; they eat the plants binding the soil, and their hooves cut up the surface and promote erosion. But it ain’t necessarily so.

Operation Hope, a Zimbabwean NGO and winners of $100,000 Grand Prize in the Buckminster Fuller Challenge, has

[T]ransformed 6,500 acres of of parched and degraded grasslands in Zimbabwe into lush pastures replete with ponds and flowing streams – even during periods of drought.

The quote is from a write-up in Seed magazine, which gives lots of details of the story. In essence, the key to livestock and grasslands is time, not numbers. If animals are on the land too long, their hooves do indeed powder the soil and they do overgraze. But if they are free to move on, or are moved by herders, moderate trampling allows rain to percolate into the soil, rather than run off and cause erosion. It also improves contact between seeds and soil, promoting germination. And dung and urine return plant matter to the soil to increase fertility and sequester more carbon, without becoming pollutants.

Operation Hope grazes animals in one spot for a maximum of three days, and they do not return for at least nine months, mimicking the natural movements of large herbivores on the savannah. At night they are protected from predators in portable kraals, which are also mobile to prevent a build-up of dung and urine. The effects are impressive. (“Animal-treated” field on the right, conventionally managed field on the left. Image courtesy Buckminster Fuller Institute”)

What’s interesting, and this is explored in much more detail in the Seed article, is that this kind of ecosystem thinking, which requires human knowledge and ingenuity to tackle complex problems, could have applications well beyond range management. Allan Savory, the scientist behind Operation Hope and the Africa Centre for Holistic Management, is hard on the Green Revolution.

“We posit the necessity of a new ‘Brown Revolution’, based on the regeneration of covered, organically rich, biologically thriving soil, and brought to fruition via millions of human beings returning to the land and the production of food.”

Of course, that’s hard work. But it is also surely much more interesting and fulfilling.

Nibbles: FAOSTAT, Drought, Seeds, Helianthus, Coffee trade, CePaCT, Figs, Old rice and new pigeonpea, Navajo tea, Cattle diversity, Diabetes, Art, Aurochs, Cocks

- FAO sets data free. About time.

- Presentation on drought risk and preparedness around the world. Nice maps.

- A Facebook for seeds?

- The diversity of Jerusalem artichoke. In France.

- Coffee certification 101.

- Nice plug for SPC’s Centre for Pacific Crops and Trees.

- The fig of choice in San Francisco.

- Back to traditional rice varieties in India. But forward to new pigeonpea varieties in Malawi. Go figure.

- Navajo tea. Would love to try it.

- “The mixed (east-west) affiliation of Mongolian cattle parallels the mixed affiliation of Mongolians themselves.”

- Lancet article mentions Lois Englberger and her Go Local work in the Pacific in context of diabetes epidemic in Asia-Pacific.

- Edible art.

- More on bringing back the aurochs. Does anyone really want one, though?

- Great variety of rare and exotic poultry breeds. Temptation to pun smuttily averted, mostly.