The iniquitous 300% tariffs imposed by the last administration on Roquefort cheese are to go. The sterling campaigning efforts of the Société Roquefort have thus been deservedly rewarded. Good news for American cheese lovers. And Occitan shepherds. Let agrobiodiversity and its products be free!

What gives wine its taste

It’s good practice to throw garbage into your vineyard, apparently. Always has been. Don’t believe me? Read the article, watch the video.

Nibbles: Tsetse, Warty pumpkins, Cattle origins, Crop mobs

- Tripping up trypanosomiasis: “It is a poverty fly.”

- Pumpkin patent squashed: “This is like trying to patent all trees with twisted limbs.”

- Indonesian bovines fingerprinted: “…the famous ‘racing bulls‘ from Madura descended from banteng cows.”

- Cropmobbing. Sounds like fun. Via.

Happy World Fair Trade Day!

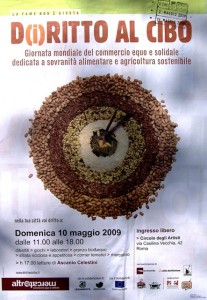

Today, May 9th is World Fair Trade Day, apparently. I had no idea until I saw this poster a few days ago. And even then there was some confusion as for some reason the date on it is the 10th.

The theme is food sovereignty and sustainable agriculture. There’s a great-looking programme being organized here in Rome. Anyway, as an old germplasm collector, I can really relate to all those seeds on the poster.

Wild pig doing just fine

Professor John Fa, director of conservation science at the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, one of the partners in the Pygmy Hog Conservation Programme (PHCP), described the pigs as “enigmatic.”

Maybe they just don’t want to get swine flu. I mean, look what happened to Khanzir.