- New York Times blog and USA Today update readers on Pavlovsk.

- Biopolitical unpacks the environmentalists’ paradox, and finds it not in the least bit paradoxical.

- New standards promulgated to protect wild medicinal plants, and wild plant collectors. Phew.

- BioBlitz in East London. Wonder if they’ll find anything edible?

Sudan gets a helping hand from Oxfam.

“I am hoping that with the diversification of food sources, we can cope with the drought without being hungry.”

Oxfam is dispensing seeds and advice in the Sudan. I wonder what varieties of sorghum and other seeds they gave those farmers?

Nibbles: Nagoya, Popghum, Pavlovsk, Water, Climate change, Plumpy’Nut, Buckwheat

- The essential guide to the 10th Conference of the Parties to the convention on Biological Diversity. Unmissable.

- Popghum? What genius came up with that name? And now that it’s big in Virginia, can Africa and Latin America be far behind?

- Jeremy Bentham excoriates the Russian Federation on Pavlovsk. And gets it mostly right. Yes, that Jeremy Bentham.

- Apparently water diversity is also a good thing for food security.

- Climate change! Huh! What is it good for? Absolutely nothing! Huh!

- “Plumpy’Nut is not a miracle cure for global hunger or for global malnutrition.” Say it isn’t so!

- Never mind wheat, here’s the great buckwheat panic of 2010, kasha chaos.

Is there really no downside to Brazil’s agricultural miracle?

It’s not easy to explain the Brazilian agricultural miracle to a lay audience in a couple of magazine pages, and The Economist makes a pretty good fist of it. It points out that the astonishing increase in crop and meat production in Brazil in the past ten to fifteen year — and it is astonishing, more that 300% by value — has come about due to an expansion in the amount of land under the plow, sure, but much more so due to an increase in productivity. It rightly heaps praise on Embrapa, Brazil’s agricultural research corporation, for devising a system that has made the cerrado, Brazil’s hitherto agronomically intractable savannah, so productive. It highlights the fact that a key part of that system is improved germplasm — of Brachiaria, soybean, zebu cattle — originally from other parts of the world, incidentally helping make the case for international interdependence in genetic resources. 1 And much more.

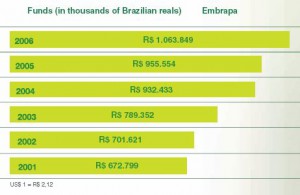

What it resolutely does not do is give any sense of the cost of all this. I don’t mean the monetary cost, though it would have been nice for policy makers to be reminded that agricultural research does cost money, though the potential returns are great. The graph shows what’s been happening to Embrapa’s budget of late. A billion reais of agricultural research in 2006 bought 108 billion reais of crop production.

What it resolutely does not do is give any sense of the cost of all this. I don’t mean the monetary cost, though it would have been nice for policy makers to be reminded that agricultural research does cost money, though the potential returns are great. The graph shows what’s been happening to Embrapa’s budget of late. A billion reais of agricultural research in 2006 bought 108 billion reais of crop production.

But I was really thinking of environmental and social costs. The Economist article says that Brazil is “often accused of levelling the rainforest to create its farms, but hardly any of this new land lies in Amazonia; most is cerrado.” So that’s all right then. No problem at all if 50% of one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots has been destroyed. 2 After all, it’s not the Amazon. A truly comprehensive overview of Brazil’s undoubted agricultural successes would surely cast at least a cursory look at the downside, if only to say that it’s all been worth it. Especially since plans are afoot to export the system to the African savannah. And it’s not as if the information is not out there.

A final observation. One key point the article makes is that the success of the agricultural development model used in the cerrado is that farms are big.

Like almost every large farming country, Brazil is divided between productive giant operations and inefficient hobby farms.

Well, leave aside for a moment whether it is empirically true that big means efficient and small inefficient in farming. Leave aside also the issue of with regard to what efficiency is being measured, and whether that makes any sense. Leave all that aside. I would not be surprised if millions of subsistence farming families around the world were to concede that what they did was not particularly efficient. But I think they would find it astonishing — and not a little insulting — to see their daily struggles described as a hobby.

How not to help after a disaster

A major study of agriculture in Haiti after this year’s earthquake has found that much of the emergency seed aid provided after the disaster was not targeted to emergency needs. The report concludes that seed aid, when poorly-designed, could actually harm farmers or depress local markets, therefore hampering recovery from emergencies.

Like the man said, those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. And where would those who rushed to Haiti’s aid have learned some history? Google? Or just this recent paper.