- Boffins to brew Jurassic Park beer.

- Boffins fingerprint weeds.

- Boffins scour arctic for antifreeze proteins.

- Boffins to reclaim Garden of Eden.

- Boffins fight to save pines in Europe.

- Boffins improve production of rice and fruits in Mekong Delta.

- Boffins to spend $US3.5billion on GM in China.

- Boffin “disgraces himself”.

- Boffin says insects are agrobiodiversity too.

- Boffin wants you to plant sunflowers and count bees. Other boffins dig up evidence of bliblical beekeeping.

- Boffins find endogenous retroviruses in sheep different to ones in wild relatives. Via.

- Boffins kill beautiful theory about pre-Columbian chickens with ugly fact.

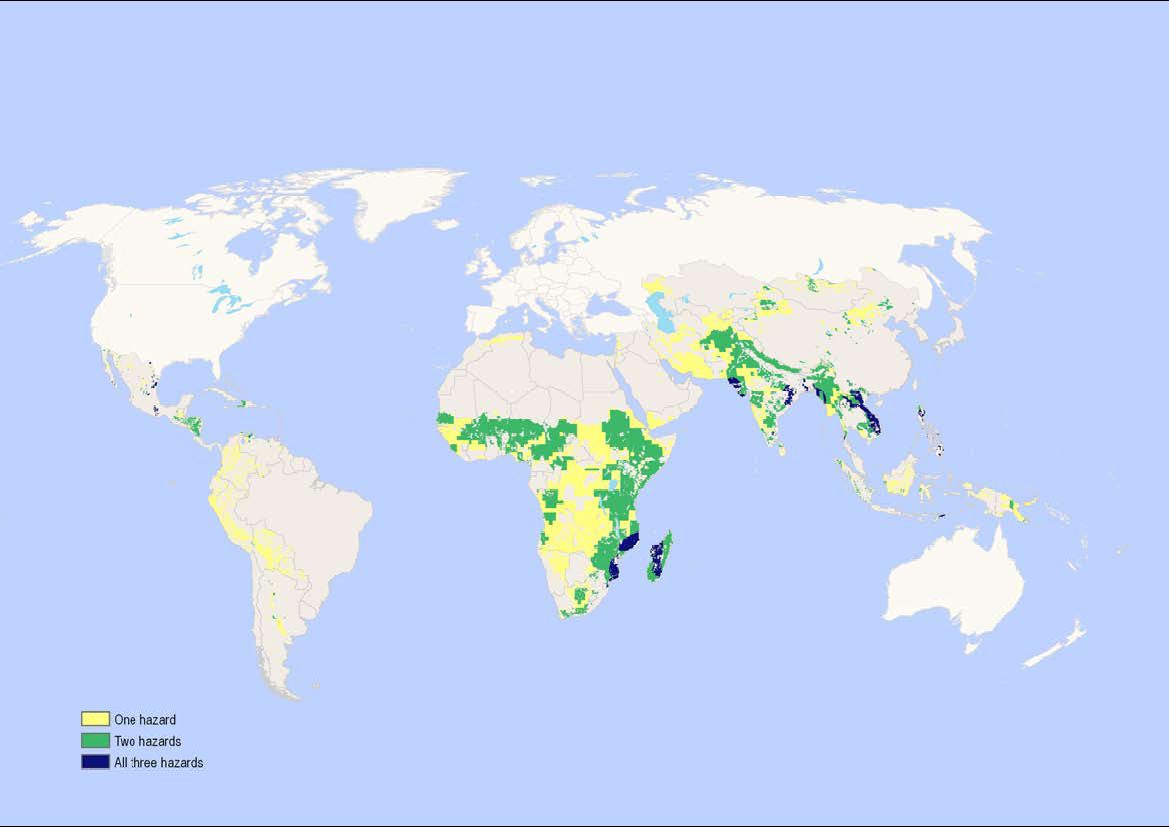

Climate change risk hotspots mapped

A SciDevNet piece on the report “Humanitarian Implications of Climate Change: Mapping emerging trends and risk hotspots” says that

The report, commissioned by CARE International and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), identifies Afghanistan, India, Indonesia and Pakistan as countries particularly vulnerable to extreme weather conditions.

But actually, looking at the map on page 26 from an agrobiodiversity conservation point of view, the countries I’d target — for germplasm collecting, for example — are Mozambique, Madagascar and Vietnam. The authors looked at flood, cyclone and drought risk. These countries are in for all three.

LATER: At least Cuba doesn’t seem to be at much increased threat, which is just as well!

Wheat a surprise

I am, I confess, very confused by two items I read yesterday. The first is an extensive report on India’s readiness to deal with the UG99 variant of wheat rust disease. The headline declares India’s wheat immune to Ug99, but on alert. Making allowances for the difficulties faced by sub-editors the world over, I read on, and discovered that 12 wheat varieties popular in India have shown some level of resistance when grown at test sites in Kenya. The article goes on to say that these are being bulked up and offered to wheat breeders and that an eagle-eye is watching “the higher hills of Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Southern hills in Tamil Nadu to detect and track down Ug99 or its variants”. There’s also reassuring talk of the time it will take for the disease to build up to a scale large enough to cause economic losses. The article’s broad, soothing conclusion:

Thus a multi-pronged strategy is already in place to render the rust ineffective even in the most unlikely event of Ug99 striking Indian territory. “We are confident and feel that such a vibrant technical programme will stand by Indian farming community and will be able to avoid any crisis likely to be caused by this disease,†ICAR said in a report.

My confusion: is this really the approach you would expect from a support-seeking government agency? ICAR is the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, and its press release on UG99 is the only source for the Commodity Online story linked to above. I’d have thought that, far from seeking to downplay fears, ICAR should be informing India and the world that without a lot more research the country’s wheat crop will remain in grave danger.

Item number two is from Reuters, seen at Guardian.co.uk. It reports on a speech that Thomas Lumpkin, the new Director General of CIMMYT, gave in Canberra, Australia. In essence, Lumpkin used current high food prices (dropping now, as farmers respond to market signals) to warn that unless the world accepts genetically modified wheat, “People will die, a lot of people will die.”

“Governments should try to help the public appreciate how much the high price of food affects the poor in developing countries,” Lumpkin told Reuters in an interview on Wednesday. “By denying them this technology, you are keeping them hungry, they are dying.”

He obviously feels strongly about that. My confusion: is CIMMYT actively researching GMO wheat, putting its money where its DG’s mouth is? Yes, but not much — roughly 0.5% of the “total research portfolio” in 2004. The greedy capitalist pigs at Monsanto and Syngenta aren’t willing to take the risk. CIMMYT doesn’t have pesky shareholders or customers to satisfy. Perhaps it will now get stuck in.

Oh, and, one final confusion. CIMMYT’s Lumpkin, unlike India’s ICAR, does think UG99 is a problem. “Wheat breeders world-wide are racing against time to control this new threat,” said the summary of his speech. Reuters didn’t mention that part.

Nibbles: Veal, Anatomy, Taro, Schwenkler, Genebanks

- “You have to find a wacky person when you are trying to rescue something in danger of extinction“.

- Fruit porn video from BBC.

- Hawaii sets up task force to save taro. Yeah that’ll work.

- John Schwenkler potpourri.

- Malaysian PM set right on seedbanks. Thanks, Choo.

Nibbles: Poppies, Gardening, Milk, Grapes, Genebanks, Meat, Biotech, IK, Plant health

- Dropping the poppy.

- Gardening on windowsills and along roadsides.

- Cooling camel milk. Via.

- Fingerprinting grapes.

- “The seed banks that are run by agribusiness corporations would be a costly pursuit for the government and farmers.” Where to start responding to this? Thanks, Jeff.

- Further evidence of food price crisis.

- “What does biodiversity mean to Syngenta?“

- Traditional healer goes online. Via.

- Videos from Global Plant Clinic.