- Vesicular arbuscular mychorriza help improve fallows.

- Google.org has a Predict and Prevent Initiative to catch outbreaks of human diseases before they happen. Would be nice to have something similar for threats of erosion of agrobiodiversity.

- Niger’s soudure food banks: could they act as village-level genebanks?

- You might call it meta-farming—the quasi-philosophical approach to raising crops and livestock that proceeds not from necessity or commercial aims but a concept.

- Farming in Russia: a slide show with narration.

- Army worm wine. WTF? Via. (They’re caterpillars.)

- A Kazak apple a day keeps the blue mold away.

- Neolithic China: not just rice.

- The oldest continuous cotton experiment in the world.

Nibbles: Women, Rats, Figs, Mammoths, Castor oil, Heirlooms, Orchards, Genebanks

- “Take into account both women’s and men’s preferences when developing and introducing new varieties.”

- Rats!

- Domestication of figs pre-dates that of cereals?

- Neanderthals liked barbecue.

- Underutilized plant in homegarden a terror threat.

- Heirloom bean farmer feted by Washington Post, added to Agricultural Biodiversity Weblog blogroll.

- Orchards as hotspots of agrobiodiversity.

- “…grass pea is a ‘poster child’…”

Malanga comes through Ike

Cuba has not been lucky this hurricane season. The latest storm to hit is Ike. Damage to agriculture has been extensive, but there is a glimmer of good news:

In Cienfuegos, plantain and sweet potato are affected, as well as vegetables and citrus such as grapefruit and orange. The one crop that hasn’t been affected is malanga – a tuber kind of like potato.

Malanga is Xanthosoma, and Cuban researchers have had a great interest in the crop.

As Grahame Jackson says in his Xanthosoma Yahoo Group post, “diversity of local food crops is so important in countries where there are threats from natural disasters, hurricanes, torrential monsoons, droughts.” Indeed. And we do have some idea of where the threats are going to be concentrated, and therefore where agrobiodiversity will be most needed.

Nibbles: Yeast, Weeds, Bioprospecting, Iraq, Pine wilt, Vietnam, GM, GM, Insects, Bees, Sheep, Fowl

- Boffins to brew Jurassic Park beer.

- Boffins fingerprint weeds.

- Boffins scour arctic for antifreeze proteins.

- Boffins to reclaim Garden of Eden.

- Boffins fight to save pines in Europe.

- Boffins improve production of rice and fruits in Mekong Delta.

- Boffins to spend $US3.5billion on GM in China.

- Boffin “disgraces himself”.

- Boffin says insects are agrobiodiversity too.

- Boffin wants you to plant sunflowers and count bees. Other boffins dig up evidence of bliblical beekeeping.

- Boffins find endogenous retroviruses in sheep different to ones in wild relatives. Via.

- Boffins kill beautiful theory about pre-Columbian chickens with ugly fact.

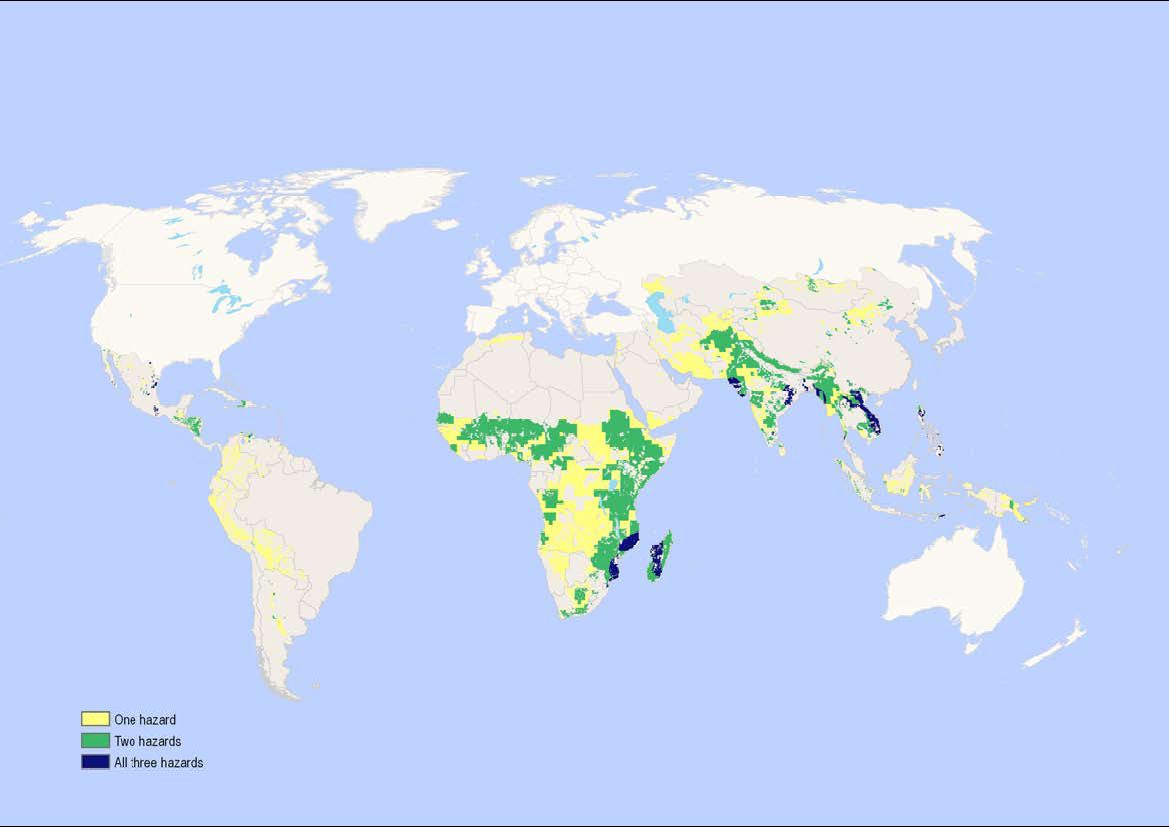

Climate change risk hotspots mapped

A SciDevNet piece on the report “Humanitarian Implications of Climate Change: Mapping emerging trends and risk hotspots” says that

The report, commissioned by CARE International and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), identifies Afghanistan, India, Indonesia and Pakistan as countries particularly vulnerable to extreme weather conditions.

But actually, looking at the map on page 26 from an agrobiodiversity conservation point of view, the countries I’d target — for germplasm collecting, for example — are Mozambique, Madagascar and Vietnam. The authors looked at flood, cyclone and drought risk. These countries are in for all three.

LATER: At least Cuba doesn’t seem to be at much increased threat, which is just as well!