FAO has a book out called Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems, published with the Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment (CINE). There’s an informative interview with Barbara Burlingame, senior nutrition officer at FAO and coordinator for the book, on the FAO InTouch website. Unfortunately, this is only available internally at FAO, for reasons which elude me. Here’s a few of the interesting things Dr Burlingame had to say.

We wanted to showcase the many dimensions of these traditional food resources, breaking them down by nutrition, health, culture and environmental sustainability. So much knowledge of early cultures is contained within traditional foods and their cultivation, and they have a direct impact on the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual health of indigenous communities. Indigenous foods can have important nutritional benefits, for example. For instance plant foods are generally viewed as good sources of carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals. These foods also provide important economic benefits, such as helping create self-sufficient communities and establishing a strong foundation of food security.

…

We believe the information can be a help to those in nutrition, agriculture, environmental and health education, and science, including policymakers. Nutritionists can use the information to try and correct imbalances in certain regions. For example, we discovered in research that the Pohnpei district community in the Federated States of Micronesia was severely deficient in vitamin A, despite the fact that a species of banana rich in vitamin A beta-carotenes was indigenous to the region. Once we determined the nutritional composition of the banana, we were able to educate the people about its benefit and encourage them to eat the local fruit, which helped reverse the deficiency.

…

Yes, another book is under way that focuses more on nutrition and public health. It will look at policy dimensions, stemming the tide of obesity in indigenous peoples, the value of indigenous weaning foods for babies, and a ‘go local’ campaign in Micronesia encouraging communities to eat local food items. We will also continue in our efforts in integrating elements of biodiversity into all aspects of nutrition.

“Go Local” of course refers to the campaign to promote traditional foods in the Pacific spearheaded by Lois Englberger and her colleagues at the Island Food Community of Pohnpei, who have appeared frequently on these pages. It’s great to see my old friends from the Pacific getting this kind of international exposure for their efforts, and making a difference beyond their immediate region.

Continue reading “Indigenous food systems documented”

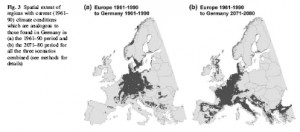

![]() Good news for sun-loving Germans. By 2071-2080 parts of their country are going to have the climate that parts of Greece have now. That’s according to a paper in Plant Ecology which ran a bunch of climate change models for Europe. 1 Have a look at the money map.

Good news for sun-loving Germans. By 2071-2080 parts of their country are going to have the climate that parts of Greece have now. That’s according to a paper in Plant Ecology which ran a bunch of climate change models for Europe. 1 Have a look at the money map.