- The musapocalypse gets an infographic.

- Celebrating agricultural biodiversity in Ethiopia.

- High calcium potato wild relatives in the news. No, really.

- NY Times catches up with the Kenyan leafy green revolution.

- The world’s prettiest (only?) coffee genealogy poster.

- The great Michael Twitty’s long-awaited book on African-American foodways is out.

- Nice video on biodiversity loss actually opens with Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

Call for articles: Valuing underutilised crops

We are looking for stories that analyse how underutilised crops have been revalued. We seek examples of communities that continued growing and processing them contrary to dominant trends. What were the successful strategies and the challenges to reviving the knowledge and the use of the underutilised crop? How did production, processing and preparation of food change? What role did markets, policy, research or local food and farmers’ movements play? What changes did this bring to rural and urban communities? What was the role of youth?

Nibbles: Value edition

- Peru to give value to its biodiversity.

- Germany already has, 500 years ago.

- Cavendish bananas have a lot of value, but that won’t save them.

- The UK’s vegetables genebank is very valuable.

- But you can always add more value to genebank collections if you evaluate them, like IRRI’s going to do in an expensive new building.

- I’m not sure what the value of Gold Rush-era heritage trees might be, but I think it’s really cool that someone’s looking for them.

- The value of genetic engineering for drought tolerance is just around the corner.

Genebanks are valuable, even without climate change

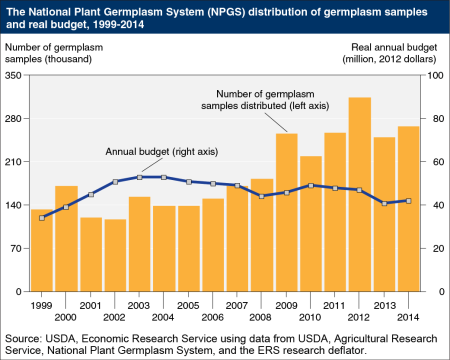

As agriculture adapts to climate change, crop genetic resources can be used to develop new plant varieties that are more tolerant of changing environmental conditions. Crop genetic resources (or germplasm) consist of seeds, plants, or plant parts that can be used in crop breeding, research, or conservation. The public sector plays an important role in collecting, conserving, and distributing crop genetic resources because private-sector incentives for crucial parts of these activities are limited. The U.S. National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) is the primary network that manages publicly held crop germplasm in the United States. Since 2003, demand for crop genetic resources from the NPGS has increased rapidly even as the NPGS budget has declined in real dollars. By way of comparison, the NPGS budget of approximately $47 million in 2012 was well under one-half of 1 percent of the U.S. seed market (measured as the value of farmers’ purchased seed) which exceeded $20 billion for the same year.

Couldn’t have put it better myself, though admittedly I’m more likely to have done it for the CGIAR genebanks than for the NPGS. The diagram, and the sentiment, derive from a USDA publication that came out back in April: Using Crop Genetic Resources to Help Agriculture Adapt to Climate Change: Economics and Policy. We did blog about it at the time, but USDA seem to be plugging it again, and I see no reason why we shouldn’t too.

Nibbles: Youthful ideas, IK, Variety testing, GMO philosophy, Organic GMOs, Oline disease, Cacao doctors, US wheat, Cary Fowler, Bison renaissance, UCDavis, Andean grains, Alaskan ag, Lettuce latex, Collecting strategies, Pulses racing, Huitlacoche, Ecoagriculture, Bowel movement

- Australian yoofs make suggestions for a better agriculture. Not as bad as you might think.

- Emulate, don’t imitate, desert dwellers.

- Webinar on variety trialing.

- A philosopher tackles GMO labelling. Not many people hurt.

- Meanwhile, Pamela Ronald is trying to find a middle way.

- This Italian olive disease thing is getting worrying.

- Indonesians have their own problems with cacao, but at least they seem to be fixing them.

- And the US is gonna have trouble with wheat. The solution: plant maize? No, wait…

- The European bison is back!

- A decade of Plant Sciences at UCDavis.

- Call for more breeding of Andean grains. By an Andean grain breeder.

- “It might not be the Fertile Crescent when it comes to corn and potatoes, but south-central Alaska just might be the cradle of the coming Rhodiola renaissance.”

- Rubbery lettuce? Shhh, or everybody will want some.

- Can’t collect seed at random throughtout a population? Collect more!

- Yeah, yeah, it’s the International Year of Pulses, we get it.

- The Mexican truffle?

- Ecofarming pays. In Kenya. In 2014.

- Sometimes crop wild relatives are a real pain in the ass.