- In the Footsteps of Vavilov: Plant Diversity Then and Now. The Pamiri Highlands of Tajikistan, the Ethiopian Highlands, and the Colorado Plateau of Southwestern North America compared at time of Vavilov and now: “Localities that have retained diversity have suffered the least.”

- Vavilovian Centers of Plant Diversity: Implications and Impacts. “His concept of specific centers of origin for crop plants was not an isolated aphorism but has directed breeders, on their study and reflection, to the continued improvement and economic development of plants for humanity.”

- Mitochondrial DNA variation of Nigerian domestic helmeted guinea fowl. Recent domestication, and lots of intermixing mean not much diversity, and what there is doesn’t have structure.

- Genome-wide association and genomic prediction of resistance to maize lethal necrosis disease in tropical maize germplasm. That’s when two viruses attack synergistically. Resistance is from multiple loci with smallish effects, and there are some promising markers.

- Genome-environment associations in sorghum landraces predict adaptive traits. Genotype predicts drought tolerance.

- Facilitation and sustainable agriculture: a mechanistic approach to reconciling crop production and conservation. Understanding facilitative plant–plant interactions (intercropping, varietal mixtures) in crops leads to more sustainable farming practices. Or it could.

- The relative contribution of climate and cultivar renewal to shaping rice yields in China since 1981. Mainly new varieties. Climate change has actually helped, but for how long?

- Biodiversity inhibits parasites: Broad evidence for the dilution effect. Meta-analysis shows biodiversity decreases parasitism and herbivory.

- Using genomic repeats for phylogenomics: a case study in wild tomatoes (Solanum section Lycopersicon: Solanaceae). Data that are usually thrown away turn out to be useful for something after all.

- Genetic structure of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) in the Old World reveals a strong differentiation between eastern and western populations. Asian and African genepools, with geneflow E to W.

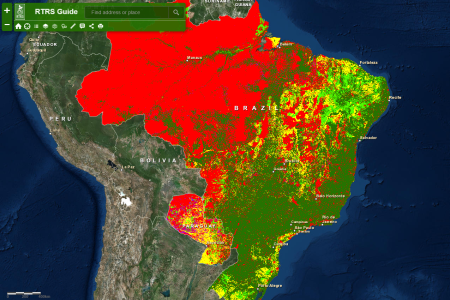

Mapping responsible soy irresponsibly

Good thinking by the Round Table on Responsible Soy (RTRS) to map where it is most — and least — environmentally responsible to extend soy cultivation in South America.

“An interesting exercise, isn’t it?” they ask. No doubt it was meant rhetorically, but I’ll answer anyway: definitely, you bet! But how much more interesting if there had been a way of adding your own data to theirs. I’d really like to know, for example, about any crop wild relatives found in those light green areas in particular: “Areas where existing legislation is adequate to control responsible expansion (usually areas with importance for agriculture and lower conservation importance).” I know where to get the CWR data. 1 But how do I mash them up with this?

Nibbles: Sustainable database, Strawberry breeding, Breeding rice, Nutrition champion, Camel milk, Mike Jackson, Feed the Future, Quinoa prices, Small is beautiful

- A database of how you do sustainable intensification.

- Building a better strawberry.

- New lab helps Bangladesh with high-zinc rice.

- Maybe those guys are you nutrition champions.

- They’re right, camel milk is good, and good for you.

- Useful list of Mike Jackson’s publications.

- Pres. Obama learns about maize in Ethiopia.

- Increased quinoa supply leads to lower prices shock.

- Silly season roundup: tiny watermelons (no, not really), tiny pineapples.

“Tomatillos silvestres, tomatillos silvestres!”

A short Smithsonian.com piece by Barry Estabrook does a really outstanding job of describing — no, explaining — the conservation and use of crop wild relatives to a lay audience. It’s all there. The value to crop breeders of genes from wild relatives. The history of germplasm exploration, and how it has resulted in the establishment of large collections. The need for, and urgency of, further collecting. The use of information from genebanks to guide future exploration. The challenges that such work faces, including on the policy side. And the euphoria that it can generate when you do overcome those challenges. All in a couple of pages, using a single wild species as an example. And if, once you finish reading the story, you want to know more about what Estabrook was chasing in Peru, it’s (probably) this.

Early agriculture in the Old and New Worlds

Last week saw the publication of a couple of papers about early agriculture in two very different regions which will probably have people talking for quite a while. From Snir et al. 2 came a study of pre-Neolithic cultivation in the Near East. And from the other side of the world, there was the latest in the controversy over the extent of Amazonian agriculture from Clement et al. 3.

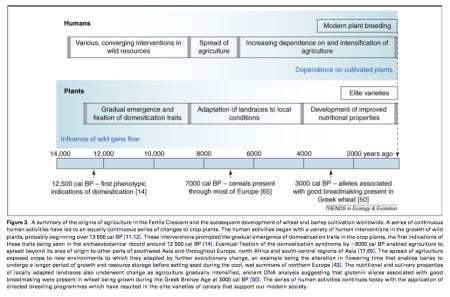

Yes, I did say pre-Neolithic. The key finding of the archaeological work described by the first paper is that 23,000 years ago, or over 11 millennia before the putative start of agriculture in the Fertile Crescent, hunter-gatherers along the Sea of Galilee in what is now Israel maintained little — and, crucially, weedy — fields of cereals. The archaeobotanists found remains of both the weeds and the cereals at a site called Ohalo II, as well as of sickles, and the cereals were not entirely “wild”, as the key domestication indicator of a non-brittle rachis was much more common than it should have been. To see what this means, have a look at this diagram from a fairly recent paper on agricultural origins in the region. 4

Those “first phenotypic indications of domestication”, dated at 12,500 years ago, need to be pushed quite a bit leftwards on that timeline now, off the edge in fact. A non-shattering rachis, it seems, was quite a quick trick for wild grasses to learn. But the process by which they acquired all the other traits that made them “domesticated” was very protracted and stop-start.

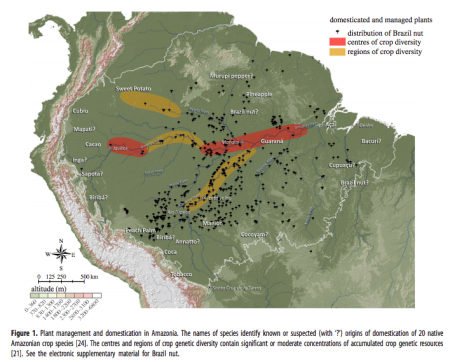

Zoom over to Amazonia, and the transition to farming took place much later, probably around 4,000 years ago, according to the other paper published last week. But it was just as significant as in the much better-known “cradle of agriculture” in the Fertile Crescent, with perhaps 80 species showing evidence of some domestication. The difference, of course, is that Amazonian agriculture was based on trees, rather than annual grasses and legumes.

According to the authors, parts of the Amazon basin, in particular those now showing evidence of earthworks and dark, anthropogenic soils, were just as much managed landscapes by the time of European contact as the places those Europeans came from. But compare our collections of crop diversity from the Amazon basin (courtesy of Genesys, which admittedly does not yet include Brazilian genebanks)…

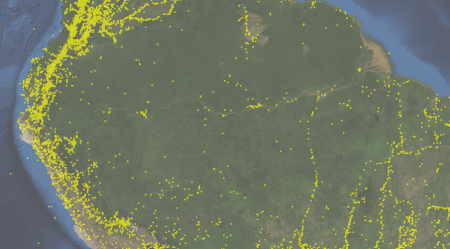

with what we have from the Near East…

If we want to know more about how the domestication process and transition to agriculture differed in the Amazon and the Fertile Crescent, there’s a whole lot of exploration still to do.