This website provides information on recommended locations, mainly in protected areas, suited for the establishment of genetic reserves for Avena, Beta, Brassica and Prunus targeted crop wild relative taxa across Europe, in the context of the AEGRO project. Available information includes ecogeographical data as well as an inventory of crop wild relatives belonging to the four target genera occurring at each location.

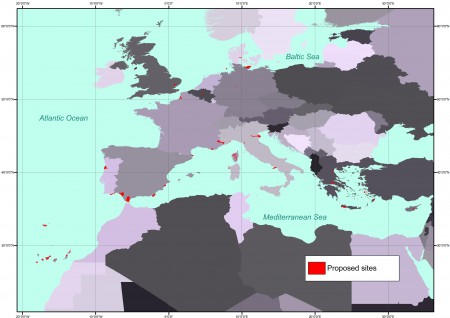

This is the map of the recommended sites:

Which is great, and even greater is the fact that you can look at individual species, and the suggested protected areas, using a nifty Google Maps plugin. This, for example, is the Estrecho site in southern Spain, which is where you find an endemic wild oat (among other things).

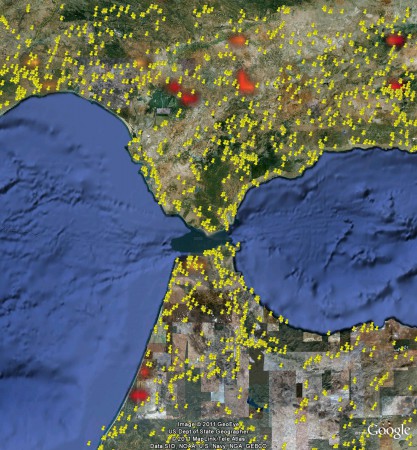

The problem is ((You knew there was a problem, didn’t you?)) that I can find no way of mashing these data up with anything else. For example, say you want to add Genesys data to see if any other species occur in this, or any other, protected area. I don’t see how. You know where those Genesys accessions are:

But there’s no way to combine the two. Or maybe you want to see if the area was affected by fires last summer. Can’t be done. You know where the fires occurred:

But there’s no way to combine the two. Whereas of course you can easily combine that NASA fire data with the Genesys data, simply by bringing both into Google Earth. ((And, yet again, thanks to Google for the Pro license. So cool.))

So I guess my plea is: if you’re going to use Google Maps or Google Earth to display your biodiversity data, please also make it downloadable. Maybe there was a reason why this couldn’t be done in this project. I’m all ears.

Oh, and there’s another thing while I’m indulging my hobbyhorses. Can’t we use some innovative approaches to add to these kinds of datasets? I mean, if it can be done for amphibians…