- British hill sheep in trouble.

- Canadian maple syrup in trouble.

- Fruits good for you.

- Native urban plants in trouble. How many crop wild relatives among them?

- “If the world learned to feed itself half a century ago, why are there now more hungry people than ever before?” Er … I dunno. Either-orism?

- “Almost all of the 300 experts at a two-day food forum in Rome this week agreed that between them they had all the answers to how to feed the world in 2050, but doubted they would have the political support to do it.” Alert the media!

- “Erosion of Crop Diversity Worrying“. Malawian plant breeder speaks.

- British wildflowers in trouble, prince says? How many crop wild relatives among them? Does prince know? Care?

- Indian crops in trouble.

Tajikistan to sustain agrobiodiversity in the face of climate change

A Google Alert pointed me to an article in the Times of Central Asia purportedly about a new Global Environment Facility-funded project in Tajikistan intriguingly entitled “Sustaining Agricultural Biodiversity in the Face of Climate Change.” Alas, the article is behind a paywall, so I wont even link to it, but some judicious googling led me to a UNDP press release. Which eventually led me to the project documents. Here are the objectives of the project in brief:

- Strengthened institutional and financial framework for the agro-biodiversity conservation and joint use of the benefits of the sustainable use of the agro-ecosystems.

- Increased mechanism of co-operation with local communities on agro-ecosystem management including the traditional knowledge of conservation.

- Ecosystem-based conservation and management of wild crop relatives established in the selected territories/communities.

- Lessons and experiences from target Jamoats created conditions for replication and expansion of conservation programmes.

A bunch of “possible interventions” are listed under each of these headings, but it’s unclear to me from the documents that are available online what will actually be done. This may be a project to write a bigger project. I just don’t know enough about how GEF works. If you know more, drop us a line.

Andy Jarvis wears his suit in support of crop wild relatives

Andy Jarvis and his parents pause for a photograph during the drunken revelries which followed his acceptance of the Ebbe Nielsen Prize in Copenhagen last Tuesday (Picture credit: Ciprian Vizitiu).

Nibbles: Introgression in sorghum, British cheese, Cassava development, Fishing

- “Farmers have quite accurate perceptions about the genetic nature of their sorghum plants, accurately distinguishing not only domesticated landraces from the others, but also among three classes of introgressed individuals, and classing all four along a continuum that corresponds well to genetic patterns. Their practices are fairly effective in limiting gene flow”

- Cheese map of Britain. Had no idea there was a National Cheese. I always liked Wensleydale.

- “I harvested part of the cassava and transported it to the nearest processing centre, where it was peeled, washed, pressed, dried and milled into cassava flour. They charged me Tsh600 per kilogramme (about half a dollar) and the market price was Tsh380 a kilo.”

- The giant Ponzi Scheme that is modern fishing.

Andy Jarvis in the limelight

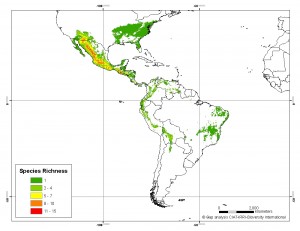

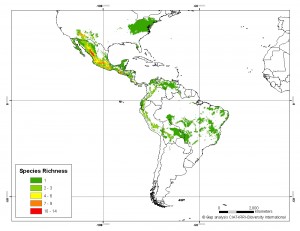

Our friend, colleague and occasional contributor Andy Jarvis received GIBF‘s Ebbe Nielsen Prize for innovative bioinformatics research last night in Copenhagen. Andy has been doing his trademark work on the spatial analysis of crop wild relative distributions 1 at CIAT, just outside Cali in Colombia, jointly with Bioversity International. He used the occasion to highlight the contribution made to this effort by his numerous Colombian colleagues. Congratulations to all of them.

LATER: Here’s Andy’s talk.