- An Evening of Conversation with Carlo Petrini: “I found it both inspiring and frustrating.”

- A retired employee of Los Alamos National Laboratory, Lopez, 70, is not your typical chile farmer.

- Wild potato confers resistance to root-knot nematode. Ask for it by name: PA99N82-4

- A simple machine for threshing sorghum and millet in developing countries. Go team!

Wild fruit relatives threatened in Central Asia

Fauna & Flora International and Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) have published a Red List of Trees of Central Asia. This is part of the Global Trees Campaign.

The new report identifies 44 tree species in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan as globally threatened with extinction. Many of these species occur in the unique fruit and nut forests of Central Asia, an estimated 90% of which have been destroyed in the past 50 years.

One of the threatened fruit trees is the red-fleshed Malus niedzwetzkyana, from Kyrgyzstan.

Working with the Kyrgyz National Academy of Sciences, the Global Trees Campaign is identifying populations of this rare tree in Kyrgyzstan and taking measures to improve their conservation. With distinctive red-fleshed fruit, the Niedzwetzky apple is an excellent flagship for the conservation and sustainable management of this beleagured forest type.

The report is available online.

A date with wild dates

A friend is going to Crete for his holidays, so I naturally suggested that he visit the populations of the wild relative of the date palm, Phoenix theophrasti, which is rare, endangered and sort-of endemic to the island. Actually there are apparently some populations in southern Turkey too, but I didn’t know that at the time. Ok, but where exactly do I find it, he asked? Give me lat/longs.

Well, I’m not sure if I managed that, but after a certain amount of googling I happened across what seems to be the mother lode of P. theophrasti information. And all conveniently packaged in a pdf pamphlet. It’s been produced as part of an intriguing project called “CRETAPLANT: A Pilot Network of Plant Micro-Reserves in Western Crete.” Great that one of the plants/habitats being targeted is a crop wild relative. Coincidentally, the genome of the crop itself has just been sequenced.

Mapping Ugandan wetlands to protect them

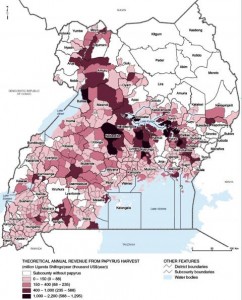

Want to know where Ugandans can make the most money from harvesting papyrus? Here you go:

This map is one of a whole series on Ugandan wetlands — their potential and the threats they face — that has just been published by the World Resources Institute 1 under the title Mapping a Better Future: How Spatial Analysis Can Benefit Wetlands and Reduce Poverty in Uganda.

One of the co-authors, Paul Mafabi , commissioner of the Wetlands Management Department in Uganda’s Ministry of Water and Environment, had this to say at the launch:

These maps and analysis enable us to identify and place an economic value on the nation’s wetlands. They show where wetland management can have the greatest impacts on reducing poverty.

There are probably some wild rice relatives lurking in these wetlands too, let’s not forget.

A new use for tubers

A sharp knife is an essential element in the preparation of many vegetables, a fact as true 2 million years ago as it is today. Results from the recent meeting of the Paleoanthropology Society, reported in Science, indicate that the people who occupied the site of Kanjera South in Kenya carried stones that held an edge better from at least 13 kilometres away. Thomas Plummer of Queens College in New York and David Braun of the University of Cape Town found that a third of the stone tools at Kanjera came from elsewhere, and that these stones made longer-lasting knives than local material.

What were they using the knives for? To butcher animals, obviously, but also to cut grass and to process wild tubers. Cristina Lemorini of La Sapienza university here in Rome showed that the pattern of wear on the ancient tools matched the wear on modern stone tools used by the Hadza people of Tanzania to process plant material. In particular, using the stone knives to cut the underground storage tubers of wild plants left a pattern of grooves and scratches that was identical on modern and two-million year old stones.

Why tubers? There have been lots of theories about the role of plant tubers in the evolution of humanity, most of which hinge on the energy to be obtained from tubers, especially when times are hard. Margaret Schoeninger, of the University of California, San Diego, floated an intriguing new idea at the meeting. She noted that most of the tubers provide scant energy, and that modern Hadza chew on slices of tuber but don’t swallow the fibrous quid. Measurements show that panjuko (Ipomoea transvaalensis) and makaritako 2 can be up to 80% water. Schoeninger thinks that early humans used the tubers as portable canteens.

That might raise the question: why weren’t they domesticated? That’s an unanswerable hypothetical, but the simple answer might be that there was just no need to.