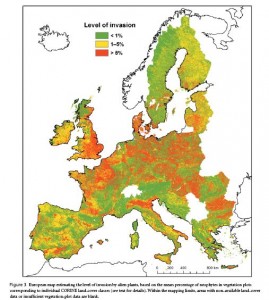

The journal Diversity and Distribution has a paper on the distribution of alien plants in Europe. You need a subscription for that, but the paper also appears to be online here, on the website of one of the authors. Here’s the map (click to enlarge it):

Could this be used to estimate the level of threat faced by some crop wild relatives?

Domestication trifecta

We’ve blogged a number of times about the paradigm shift that’s occurring among students of plant domestication, driven by increasing interaction and synergy between archaeologists and geneticists. The idea of “rapid, localised” domestication is down if not out: all the talk these days is of domestication as a protracted, multi-locational and biologically complex process.

Well, there’s a very nice review of the history of this shift in Trends in Ecology and Evolution, at least as it concerns the crops domesticated in the Fertile Crescent. It is only very recently that geneticists have looked at their molecular data in the light of archaeological results and realized that there were other ways to interpret them apart from the conventional idea of domestication in one place over the course of a few human generations.

Meanwhile, a paper in Annals of Botany looks at another source of data, i.e. written sources. Chinese investigators have looked at references to eggplants in ancient encyclopedias, concordances and even poetry, and charted changes in size, shape and taste over the past 2000 years. The oldest reference dates back to 59 BC, and since then the Chinese eggplant has gone from round to a variety of shapes, has increased dramatically in size, and has become much sweeter.

Finally, our friend Hannes Dempewolf and co-authors have a paper in GRACE which looks in detail at domestication in the Compositae. Why have only a handful of species in this family been fully domesticated? Secondary defence compounds, inulin as a storage product and wind dispersal, the authors suggest.

El hombre de la papa

Here is a video about the life and work of Carlos Ochoa, the recently deceased potato man. By the Televisión Nacional del Perú, in Spanish. From his early days in Cusco, resisting a father that wanted him to become a lawyer, to the agony of an approaching end, with so much of his life’s work unfinished. Watch, listen, admire, and shiver.

Ex situ conservation of endangered plants of the US

An interesting post on the Denver Botanic Garden’s blog led me to the Center for Plant Conservation‘s 1 database of the National Collection of Endangered Plants of the US, which I’m ashamed to say I knew nothing about. It is interesting to us here because it includes crop wild relatives like Helianthus species. There’s also lots of information on how to fight invasives, which has been the subject of some discussion here in the past few days.

Carlos Ochoa

Carlos Ochoa — legendary potato breeder, explorer and scholar — has passed away at an age of 79 in Lima, Peru.

Born in Cusco, Peru, Ochoa received degrees from the Universidad San Simon, Cochabamba, Bolivia and from the University of Minnesota, USA. For a long time Ochoa worked as a potato breeder. He combined Peruvian with European and American potatoes to produce new cultivars that are grown throughout Peru.

Ochoa was professor emeritus of the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Peru. In 1971, he joined the International Potato Center, where he worked on the systematics of Andean cultivated and wild potatoes. His long list of publications on this topic include hefty monographs on the potatoes of Bolivia and on the wild potatoes of Peru.

His last major published work (2006) is a book on the ethnobotany of Peru, co-authored with Donald Ugent.

Ochoa was a wild potato explorer par excellence. One third of the nearly 200 wild potato species were first described by him.

Carlos Ochoa received many international accolades, including Distinguished Economic Botanist, the William Brown award for Plant Genetic Resources, and, together with long time collaborator Alberto Salas, the Order of Merit of the Diplomatic Service of Peru.

Here is Ochoa’s own story about some of his early work, including his search for Chilean potatoes described by Darwin and his thoughts on potato varieties: “[they] are like children: you name them, and in turn, they give you a great deal of satisfaction”.

¡Muchas gracias, professor!