The story of the 800-year old squash seeds has surfaced again. We blogged about it way back, pointing out that it was, in fact, fake. But Archaeology Review does a great job of debunking it yet again. Be careful out there, people.

The spread of agriculture in Europe, genebank edition

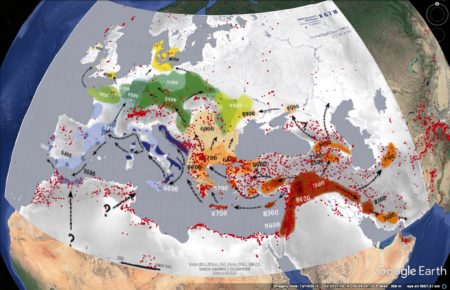

A recent Nibble pointed to an image of new, updated map of the expansion of agriculture in Europe. As is usually the case when I see almost any map, I immediately started to think about mashing it up with the localities of genebank accessions. Downloading barley landrace data from Genesys and importing it into Google Earth was easy. And you can also import an image into Google Earth, so it is theoretically possible to superimpose accessions on spread of agriculture.

Unfortunately, the practice is not straightforward, because you have to distort the image by hand to fit neatly on top of the map in Google Earth, and that can take a while. I gave up after about an hour, and after some googling eventually found Map Warper, which does the distortion for you for free. Importing the warped map into Google Maps resulted in a perfect fit.

So here’s the result.

It looks like there are barley landrace accessions from most of the areas highlighted, with dates, in the spread of agriculture map, though they are by no means all equally covered. At least as far as Genesys knows. There have of course been a number of studies looking at the geographic pattern of distribution of genetic diversity in barley in and around Europe. As far as remember, none of them explicitly took into account how long the crop had been in different places. But the material could be available for such a study to be done.

Brainfood: Barley diversity, Chinese veggies, Perennial legumes, Ecosystem value, Wild restorer, Eggplant taxonomy, Sweet potato phenotyping, Grass pollen, Aromatic rice origin, Orange cucumber, Watermelon breeding, Livestock value, Wild apples

- Genome-Wide Association Mapping of Seedling Net Form Net Blotch Resistance in an Ethiopian and Eritrean Barley Collection. 8 new QTLs, just like that.

- Vegetable Genetic Resources in China. 36,000 accessions. Just like that.

- Building a botanical foundation for perennial agriculture: Global inventory of wild, perennial herbaceous Fabaceae species. Check out the Perennial Agriculture Project Global Inventory.

- Ecosystem services and nature’s contribution to people: negotiating diverse values and trade-offs in land systems. Biological diversity has a diversity of values. Duh.

- Development of a drought stress-resistant rice restorer line through Oryza sativa–rufipogon hybridization. From F6 via BC5F5 to BIL627.

- Eggplants and Relatives: From Exploring Their Diversity and Phylogenetic Relationships to Conservation Challenges. The taxonomy is “arduous and unstable.”

- Morphometric and colourimetric tools to dissect morphological diversity: an application in sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.]. Beyond colour charts. Way beyond.

- Chemotaxonomy of domesticated grasses: a pathway to understanding the origins of agriculture. Fancy maths can identify pollen grains.

- Origin of the Aromatic Group of Cultivated Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Traced to the Indian Subcontinent. Arose when japonica hybridized with local wild populations.

- Orange-fleshed cucumber (Cucumis sativus var. sativus L.) germplasm from North-East India: agro-morphological, biochemical and evolutionary studies. Possible niche market?

- Progress in genetic improvement of citron watermelon (Citrullus lanatus var. citroides): a review. These are all orange-fleshed.

- Review: Domestic herbivores and food security: current contribution, trends and challenges for a sustainable development. Can’t live without them, but gotta do something about that enteric fermentation.

- Evaluation of Malus genetic resources for tolerance to apple replant disease (ARD). It’s the wilds, of course.

The past and future of the Silk Road

An interview with Robert N. Spengler III, author of Fruit from the Sands: The Silk Road Origins of the Foods We Eat 1 reminds me that there have been a couple of interesting papers about that part of the world recently that I was meaning to blog about.

- The domesticated apple originated half way along the Silk Road, and spread in both directions, changing most drastically in Europe due to intensive introgression from the crabapple. And more.

- In contrast, citrus fruits originated in SE Asia, and spread westward, Citrus medica (citron) reaching the Mediterranean first, and C. limon (lemon) second, both in antiquity.

- There were northern and southern routes of crop movement through central Asia, plus a maritime route.

Given the importance of the Silk Road in the domestication and the spread of crops, it is perhaps worth asking if the Belt and Road Initiative could be an opportunity for significant conservation actions. WWF has done a preliminary environmental impact assessment, but not focusing particularly on agricultural biodiversity.

Good-bye to all that Annex I?

The ninth meeting was held last week of the snappily titled Ad Hoc Open-ended Working Group to Enhance the Functioning of the Multilateral System of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The indispensable Earth Negotiations Bulletin provides a summary of the results.

You’ll remember the Treaty has entrusted this working group with the task of looking for ways of increasing and speeding up the flow of money into the Benefit Sharing Fund. The meeting came up with a package of measures, comprising revisions of both the Standard Material Transfer Agreement used to distribute germplasm from the Multi-lateral System (MLS) and the list of plant genera included in the MLS (Annex I).

As far as the latter is concerned, there was agreement on a significant expansion:

Participants achieved an important breakthrough on Thursday night, with a tentative agreement on amending the list of crops in the MLS, currently in Annex I of the Treaty. While as usual in international negotiations, “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed,” Working Group participants expressed satisfaction with the well-balanced compromise: the MLS would cover all PGRFA under the management and control of parties and in the public domain that are found in ex situ conditions, while parties have the right to make reasoned declarations exempting a limited number of native species.

And as for the other side of the coin, it seems that there will be a move towards a subscription system, where a single up-front payment buys you access to the MLS for a specified period, while allowing the current pay-for-use system as an exception:

With agreement that the subscription system would be the main approach and single access would be the exception, the proposal to set a lower rate for the primary model and a much higher rate for exceptional single access to attract more users and hopefully more funds garnered significant interest.

Predictably, not everyone is entirely happy about how things have been going. But negotiations continue, with the final package to be discussed at the next meeting of the Governing Body of the Treaty in November.