- Future flooding tolerant rice germplasm: Resilience afforded beyond Sub1A gene. You want to make rapid breeding progress? You need the “Transition from Trait to Environment” approach. As far as I can tell, this means that you fix your trait of interest in a pool of elite parents before using it in proper yield breeding.

- Prioritizing parents from global genebanks to breed climate-resilient crops. Yeah but how do you find your trait of interest in the first place. You start with passport and genotyping data from genebank collections of course.

- Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) landraces in Mozambique and neighbouring Southern African countries harbour genetic loci with potential for climate adaptation. You see what I mean?

- Genetic diversity and population structure of Colombian sweet potato genotypes reveal possible adaptations to specific environmental conditions. Ok, now do you see what I mean?

- Genetic diversity analysis and duplicates identification of new sweetpotato accessions collected in China. Manage your duplicates though, right?

- The lesser yam Dioscorea esculenta (Lour.) Burkill: a neglected crop with high functional food potential. This doesn’t have decent collections, let alone duplicates.

- Molecular screening of wild and cultivated tomato germplasm reveals potential materials for multi-locus disease resistance breeding. Again, thank goodness for genebanks — plural.

- First report on trait segregation in F1 hybrids between the cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and the wild incompatible species A. glabrata Benth. I wonder if this could be used in tomato.

- A blueprint for tapping the wild relatives for crop improvement: A success story of CWR-derived rice varieties, Nông Dân 1 and Nông Dân 2. No need for embryo rescue here. No word on the need for submergence tolerance.

- Genetic diversity in in situ and ex situ collections of sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] landraces. Diversity is still out there, at least in India. Which is great. But how would you know without genebanks? And you need genebanks for breeders to use it.

- And to cap things off, a new occasional feature: A ChatGPT-generated one-sentence summary of the week’s Brainfood. “To breed crops for climate resilience and future food security, you need to systematically mine, manage, and mobilize the diversity stored in genebanks—especially landraces and wild relatives—and integrate it into elite breeding pipelines using smart, trait-targeted strategies.”

Erna vs Otto

Is it possible to distil the ongoing debate over how to conserve plant genetic resources into the contrasting views of two people?

For Julia Nordblad of the Department of History of Science and Ideas, Uppsala University, the answer is a resounding yes, if the two people are Otto Frankel and Erna Bennett, both very much friends of the blog. She sets out her argument in a paper that is just out:

…Frankel and Bennett exemplify that there are indeed different versions of planetary temporalities that imagine the entanglements between the social and the planetary differently, and thus end up promoting distinctive politics for amending diversity loss and saving evolution. For Frankel, the solution lay within the temporality of development. Modern technology could be used to replace the storage of evolutionary time in the “primitive” agriculture, and progressive norms could emerge that would achieve protection of wild evolutionary time in the natural world. For Bennett in contrast, development was not the only possible historical trajectory, but a particular historical process driven by economic and political interest. Her vision of how evolutionary time should be protected was to let it be decentralized in varied agricultural practices shielded from corporate interest that would otherwise quickly drive diversity down and eclipse the evolutionary temporal horizon.

So it’s possible. But is it helpful?

Well, I’m torn. You can certainly find descriptions of the early days of the crop diversity conservation movement that have a larger cast of characters. Like for example the equally recent Australia’s Search for Greener Pastures: The Foundations of the Global Genetic Resources Movement, 1926-1980 by Derek Byerlee. Or the earlier but still canonical Scientists, Plants and Politics: A History of the Plant Genetic Resources Movement, by Robin Pistorius.

But there’s something satisfyingly protean about Bennett and Frankel — and indeed their sort-of-rivalry. So I’m going to say that it is indeed helpful — at least to get you started understanding this history.

And speaking of protean: where would Vavilov stand? If I read another recent paper correctly, by Jeffrey Wall of the University of Turku, somewhere in the middle. Probably a good place to be.

How to stay in touch

Attentive readers will have noticed that the little service we used to have here, whereby you’d get an email whenever there was a new post, is no longer available. Sorry about that. The reason is that it was too expensive. I do share new posts on my social media, but the best way to keep abreast of developments here remains our RSS feed. Nobody talks about RSS any more, but if you hate algorithms, it’s the way for you to follow the sites you want, the way you want. Just choose a feed reader and insert the link. It’s really easy, and liberating in a way. But if you don’t want to mess with a feed reader, and don’t mind an ad or two, you could try Blogtrottr. Just give it the RRS link and your email, choose “daily digest,” and sit back and wait for the email alerts to flood into your inbox. I’ve tried it and it’s ok.

Modified ecosystems and the conservation of crop diversity

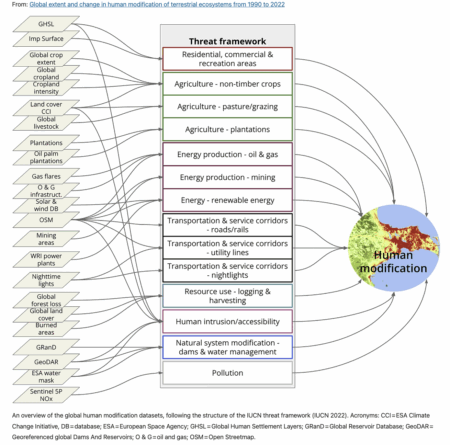

A new global assessment of the state of terrestrial ecosystems has just been published, focusing on the extent of human modification due to “industrial pressures based on agriculture, forestry, transportation, mining, energy production, electrical infrastructure, dams, pollution and human accessibility.” 1

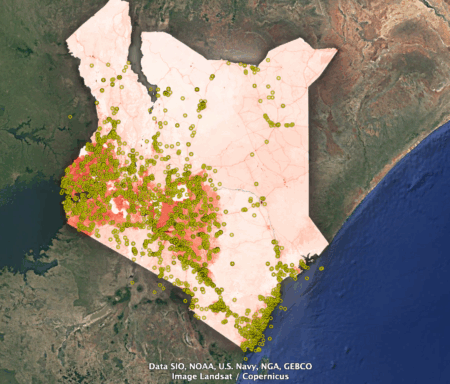

As is my wont, I tried to find a form of the data that I could shoehorn into Google Earth, but I failed. Fortunately GIS guru Kai Sonder of CIMMYT was able to snip out a kml file of overall human transformation as of 2020 covering Kenya — don’t ask me how. But thanks, Kai. I put on top of it genebank accessions from Kenya classified as wild or weedy in Genesys.

I don’t know quite what to make of this. The wild populations seem to have been mainly collected in areas that in 2020 were very highly affected by human activity. But is that good or bad?

It could be good — in a sense — if the high degree of human transformation means that the original populations are not there any more. 2 Phew, good thing they were collected! On the other hand, it could be bad if the concentration on easily accessible and modified areas means that the genetic diversity currently being conserved is not representative of what’s out there.

What do you think?

But of course what I really want is a version of this which focuses on agricultural areas and is updated in real time. Yes, a perennial favourite here: a real early warning system for erosion of crop diversity.

Another opportunity for opportunity crops

Time to register!