- The anthocyanin content of blue and purple coloured wheat cultivars and their hybrid generations. In other news, there are blue and purple wheat cultivars.

- Phylogenetic relationships and Y genome origin in Elymus L. sensu lato (Triticeae; Poaceae) based on single-copy nuclear Acc1 and Pgk1 gene sequences. It’s a very diverse genus, probably polyphyletic, and has exchanged genes with Aegilops/Triticum in the past. And could again in the future, presumably.

- Microsatellite Markers for the Yam Bean Pachyrhizus (Fabaceae). They work, both on the 3 (sic) cultivated species and 2 wild relatives.

- The domestic livestock resources of Turkey: inventory of pigeon groups and breeds with notes on breeder organizations. 72 breeds? Really?

- Land use impact assessment of margarine. Land occupation by the crops involved has a bigger impact on ecosystem services and biodiversity than the transformation process.

- Bio-cultural refugia — Safeguarding diversity of practices for food security and biodiversity. Important for food security locally, but also because of the memories of how the “surprises of the past” were handled.

- Farmer’s choice of seeds in four EU countries under different levels of GM crop adoption. More GM adoption = less choice. For maize in 4 European countries anyway.

- Sorghum landraces patronized by tribal communities in Adilabad district, Andhra Pradesh. And now safe in NBPGR too.

- Molecular characterization of oil palm Elaeis guineensis Jacq. materials from Cameroon. It’s all one big populations, and you don’t need that many accessions to represent the whole.

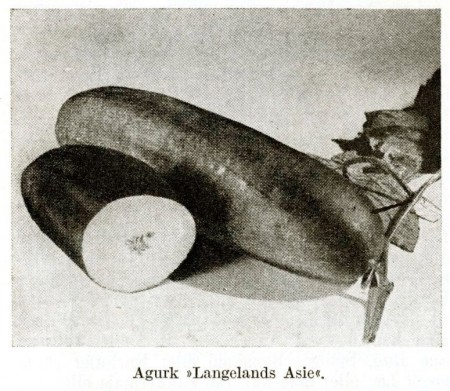

In search of the elusive asier — pickling cucumbers with a difference

Fermentation is absolutely my favourite food process. Not just for bread, beer and yoghurt, but also for proper pickled cucumbers. 1 So when a bread-baking blog I follow wrote about recreating a long-ago taste of pickled cucumbers, my heart went pitter-pat. I read Joanna’s story, and skipped on over to the recipe itself. Alas, these are not proper pickles. Indeed at one point the author insists “Be sure that when you boil the vinegar for the second time that it’s a good full, rolling boil to kill any bacteria”. Not my kind of thing at all. I could have just called it a day, except that there’s another aspect to the story that got me going. The cucumbers themselves seem to be rather special. Not easy to search online for, because most search engines seem to think you’re interested in Asia, so I went all social and put a call out to my friends in places where they might know about these things. 2

Ah yes, said Ove:

They are a group of cucumbers with thicker “flesh” than ordinary cucumbers. “The ‘Nordic Encyclopedia of Horticulture’ (5th edition 1945) names four varieties: ‘Dansk Asie’, ‘Langelands Asie’, ‘Middellang’ and ‘Ideal’”.

And he helpfully provided a photo.

Though there’s something to be said for pickled cucumber seed cavity, it isn’t much, so now I was very intrigued. I turned, first, to the USDA’s descriptors for Cucumis. That offers two characteristics of interest: cavitydiam, measured in mm at the thickest part of the fruit, and frtdia_a, measured likewise in cm. A quick download and mashup, and I’d have a seed cavity to fruit diameter ratio for all the cucumber accessions! Unfortunately, although they are listed as characteristic descriptors for Cucumis species, I couldn’t find a way actually to search for them. Agriculture and Agrifood Canada was even less helpful. 3 A document from ECP/GR mentioned flesh thickness and seed hull (which could be cavity or testa, I suppose) but was no more helpful.

Ah but … I had names! USDA knows nothing about the names from the Nordic Encyclopedia of Horticulture. The Garden Seed Inventory (6th edition) from Seed Savers Exchange does however list Langelang Giant 4 and says it has “white flesh with excel. texture, small core”. Langelands Kæmpe (Langelands Giant) is still available in Europe and a similar variety called Fatum in Germany. The Seed Savers Exchange Yearbook for 2012, which lists all varieties offered by members, doesn’t seem to have any of the named varieties, although there are several that have larger or smaller cores than normal.

Most interesting, for me, was an entry for Danish Pickling in Vegetables of New York, Vol I Part IV, The Cucurbits.

This is a comparatively new variety which was introduced in 1912 by L. Daehnfeldt of Odense, Denmark … The variety produces fruits which are extremely large and long and thickly covered with fine spines. … Flesh medium thick, very fine texture, white in color, rather tart. Seed mass small and solid, with few seeds formed.

It is hard to tell how spiny Joanna’s Langelands is, but I think I see quite a few.

I couldn’t find much trace of any of the others in the Internet, with no useful sign of Ideal, probably because the word is just too common, even in conjunction with cucumber. However, the 1975 European Common Catalogue lists Ideal as a synonym of Delikateß added at that date, while Middellang was deleted from the common catalogue.

And there I came almost to an end. The name “asier” remained a puzzle. Were these Scandinavian favoured cucumbers originally from Asia? No, said Ove. “Asie (singular, asier is the plural) comes from Indian/Persian achár, originally meaning ‘bamboo shoots pickled in vinegar and spices’.” To which Stephen added “Wonder if it’s related to the as- in asparagus which also means shoot, also from west Asia..?” Over to you, philologists.

And what have I learned? That it remains incredibly difficult to find varieties with specific characteristics, even when you know what you’re looking for. That a cucumber with a small seed core is probably a great idea, even if you’re not planning to ferment it. That I would quite like to try growing it (hint, hint).

Oh, and that not everyone is as keen on fermentation as I am. If you want to get a bit deeper into it, can I recommend this very introductory podcast, in which, among other gems, Sandor Katz – fermentation revivalist – expressly compares the value of diverse microbes in fermentation and diverse varieties on farms?

What’s eating India?

Resources Research undertook a labour of love to produce this graph. It shows, for 20 Indian states, roughly how much of pulses and cereals each tenth of the population eats each month. I urge you to go and read the full post for the details.

Bottom line: Of the 200 populations, 43 are “severely deficient” in cereals and pulses required per month.

The graph is based on data from national surveys of “Consumer Expenditure,” so I don’t know whether it includes food people grow rather than buy, but I doubt that makes much difference overall.

Makanaka makes lots of interesting points about the data, comparing the 2009-2010 survey with a similar one done five years before. Overall, this is a terrific example of open data allowing people to offer alternative interpretations to the standard line.

Brainfood: Wheat breeding, Wild chicken diversity, Wild rice diversity, Sustainable biofuels, Biofuels and biodiversity, Land sparing & sharing, Soil fertility, Cooking cassava, Cherimoya value chains

- Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Tetraploid Wheats (Triticum turgidum L.) Estimated by SSR, DArT and Pedigree Data. Diversity in morphology and storage proteins in Italian durum varieties decreases after 1990, but not in molecular markers.

- Genetics driven interventions for ex situ conservation of red junglefowl (Gallus gallus murghi) populations in India. 9 birds from the most diverse population of 4 were selected to breed with all the others to rescue them from the perils of inbreeding.

- Geographic variation and local adaptation in Oryza rufipogon across its climatic range in China. Some variation correlated with geography, but plenty of plasticity too.

- Debate: Can Bioenergy Be Produced in a Sustainable Manner That Protects Biodiversity and Avoids the Risk of Invaders? It depends. But they’re not talking about agricultural biodiversity.

- Scenarios for future biodiversity loss due to multiple drivers reveal conflict between mitigating climate change and preserving biodiversity. Looks like growing biofuels to counter climate change might not be a great biodiversity conservation strategy. But we knew that from the above.

- Beyond ‘land sparing versus land sharing’: environmental heterogeneity, globalization and the balance between agricultural production and nature conservation. As the scale of analysis increases, you have to be more careful about addressing environmental heterogeneity. You mean like mosaics?

- Overview of long term experiments in Africa. Rotations are better than monoculture for soil fertility. Well, it’s good to have the data.

- Effects of boiling and frying on the bioaccessibility of β-carotene in yellow-fleshed cassava roots (Manihot esculenta Crantz cv. BRS Jari). Fry away. Finally some good news.

- Value chains of cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) in a centre of diversity and its on-farm conservation implications. They can be bad.

Could plant diversity become free (as in speech)?

I’ve been tremendously privileged to be at the Seed Savers Exchange 33rd Annual Campout and Conference in Decorah, Iowa. It’s a wonderful gathering of people interested in saving and sharing seeds, with all sorts of workshops, practical classes, and speakers. One of this year’s speakers was Jack Kloppenburg, of the University of Wisconsin. Kloppenburg wrote First the Seed (now available in a second edition), which is the best analysis of the economic nexus that surrounds seeds and plant breeding. He told the audience he was “here to share an idea, just like you guys share seeds.” So I’m sharing his idea: the Open Source Seed Initiative.

Kloppenburg set out his ideas in a 2010 paper in the Journal of Agrarian Change. In it, he rejects what he calls the “accomodationist” approach to patents and other efforts to restrict access to plant genetic resources. Accomodationists, he says, seek “market mechanisms for compensating those from whom germplasm is being collected”. Instead, he proposes a more radical approach derived directly from the open source software movement. The Open Source Seed Initiative prevents the privatisation of plant genetic resources and, in Kloppenburg’s view, also “might actually facilitate the repossession of ‘seed sovereignty’”.

Open source software is accompanied by a licence that encourages people to share it and create new programs with it, and at the same time prevents anyone from releasing a program that uses the code under any other form of licence. The creativity embedded in the code cannot be privatised. Kloppenburg and a group of like-minded seed companies, plant breeders and academics want to apply similar licences to plant genetic resources.

Kloppenburg is at pains to point out that actually he has nothing against plant patents, other intellectual property rights, contractual “bag-tags” or any of the other mechanisms that commercial breeders use to enforce ownership of their products.

“The problem isn’t the tool,” he told the conference. “The problem is who is using the tool and why.”

There have been three meetings so far to discuss the Open Source Seed Initiative, and although the details have yet to be worked out the underlying concept is simple. An OSSI licence allows me to give you seed (or any other form of plant genetic resources) with only one condition: that you have to share it, and anything you create with it, with exactly the same condition attached.

“It becomes viral,” Kloppenburg explained. “Now ‘viral’ is kind of problematical for people in agriculture,” he conceded, “but it is. It propagates.” As it does so, it creates a protected commons, as opposed to an open commons, of things that can be freely shared but not privatised. That is OSSI’s great potential strength, according to Kloppenburg.

“People who will share are unrestricted. People who won’t share aren’t interested.”

The general idea of a protected commons for plant genetic resources bubbles up from time to time, Kloppenburg told the audience, citing Richard Jefferson’s CAMBIA initiative as one manifestation. He credits the germ of OSSI to Tom Michaels, a bean breeder then at the University of Guelph in Canada, who in 1999 proposed the idea of a general public licence for plant germplasm, or GPLPG.

Kloppenburg stressed that the lack of a monopoly does not mean a lack of payments. As with open source software, there are many ways in which plant breeders and others can seek payment for their services. There could be different forms of OSSI licence, allowing royalty payments to the breeder on the first transfer. And seed companies would be free to charge for OSSI-protected varieties.

Many details remain to be worked out. Who will police the licences, and how? Will it be possible to discover traits shared under OSSI and then incorporated into privatised varieties? How could that be proved? And the global plant genetic resources community has yet to start a serious discussion of the idea. That may prove a hard sell after the long struggle to obtain the current International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, which Kloppenburg doesn’t think is working.

The really radical route to establishing a just and agronomically productive regime for managing flows of crop germplasm is not to arrange payment for access to genetic resources, but to create a mechanism for germplasm exchange that allows sharing among those who will reciprocally share, but excludes those who will not.

The current material transfer agreement that accompanies plant germplasm under the International Treaty has some elements of an open source licence about it – but could go much further. Is there any chance CGIAR genebanks, whose holdings constitute the bulk of germplasm available under the International Treaty, could actually lead the way to the just and productive regime that OSSI is looking for, or are they too beholden to the private sector?