The Livingstone Online website coming up pretty much out of the blue on my Facebook timeline a couple of days back reminded me that I had wanted to point to the online database of the Kew Economic Botany Collection, if for no other reason than that we haven’t done it before, and that the collection includes seed samples, not least a few collected on the good doctor’s expeditions. Then of course they went and posted something about the database on their blog yesterday. Anyway, we’ve talked about the potential value of museum seed specimens before. In particular, if you search for “sorghum seed” in this case you get (among other things) what is clearly a rather remarkable collection of material from Tanzania, sent to Kew in 1934 by the “Director of Agriculture.” Each seed sample is labelled with a local name. Wouldn’t it be great to go back and see if landraces with those names can still be found, and maybe even compare their DNA with anything that can be extracted from these old seeds?

D Landreth not so important to seed diversity

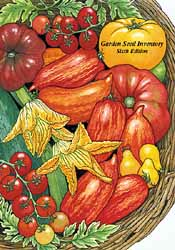

Thanks to the very good offices of our friends at Seed Savers Exchange, I now have a copy of the most recent (6th) edition of the Garden Seed Inventory. I wanted this in order to see whether the loss of The D. Landreth Seed Company, America’s oldest, as it happens, while tragic for the business and its customers, would also be a great loss for agricultural biodiversity. Long answer short: not so much.

Thanks to the very good offices of our friends at Seed Savers Exchange, I now have a copy of the most recent (6th) edition of the Garden Seed Inventory. I wanted this in order to see whether the loss of The D. Landreth Seed Company, America’s oldest, as it happens, while tragic for the business and its customers, would also be a great loss for agricultural biodiversity. Long answer short: not so much.

The Garden Seed Inventory is a catalogue of catalogues, listing all the varieties available from all the catalogues SSE can get its hands on. That makes it a very useful snapshot of what is out there (in the US), how widely available it is, and the ebbs and flows in comercially-available diversity of crops and varieties. The Introduction to the book contains lots of analysis of this type, and I thought I remembered that it listed all the varieties that are available only from a single supplier and each supplier’s “unique” varieties. It doesn’t.

It does, however, list the 27 companies (10% of the total number covered by the inventory) that list the most unique varieties. D. Landreth is not among them. It also lists the companies that had introduced the most “new unique varieties”. Perhaps unexpectedly, there’s quite an overlap with the “most uniques”. and D Landreth isn’t in that list either. All of which suggests to me that while the passing of D Landreth would indeed be sad for its owners and customers, it would not be an immediate disaster for commercially-available agricultural biodiversity in the United States.

Does D Landreth have any varieties not available elsewhere? That one is difficult to answer using the Inventory. More than 450 pages of closely spaced entries is a lot to look through, searching for those with a single source coded La1. It ought to be a doddle from the database that stores the original records, but I’m sure SSE has much else on its mind at the moment. Mind you, if 45 owners of the Inventory were to scan 10 pages each …

Finding your way in the agricultural spatial data jungle

The recent announcement of a major rethink for the HarvestChoice website sent me on a voyage of discovery. Remember that HarvestChoice, “a partnership between IFPRI and the University of Minnesota, generates knowledge products that help guide strategic investments to improve the well-being of poor people in Sub-Saharan Africa through more productive and profitable farming.” That classically includes maps. And there are definitely a lot of spatial datasets on the site. And in Mappr there is a potentially useful online tool for combining different layers and summarizing the results. No doubt a valuable site.

But let me focus here on a separate issue, and that is whether the resources available globally to develop and present such data, in such sites, are being used, er, optimally. The question occurred to me when, in exploring the maps available at HarvestChoice, I came across a dataset labelled “Cattle population (head) (2005).” The source for the data is helpfully provided:

HarvestChoice/IFPRI 2010/FAO. 2007. Gridded livestock of the world 2007, by G.R.W. Wint and T.P. Robinson. Rome, pp 131.

The funding agency is given as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and data availability is described as follows:

Data available for download in CSV format. Spatial data layer may be explored using MAPPR and downloaded in geoTIFF and ASCII raster formats.

Now, the 2007 FAO publication referenced as the source of the data is downloadable as a pdf from FAO. But the data are also available in a variety of formats from the FAO Animal Production and Health Division website. Among the formats FAO (and only FAO) offers is a Google Earth file, which is probably going to be the most useful for the average user.

And then there’s ILRI. Map 4 in their monumental Mapping Poverty and Livestock in the Developing World of 2002 does not look too dissimilar to the above, though it may be based on older data. It’s a pdf, of course, but for all I know the data are also available in a more useable format somewhere on the ILRI website. I can’t be sure because their database of GIS datasets is just too clunky to spend any significant time struggling with, frankly. Which is not to say that I didn’t…

So what exactly has HarvestChoice added to the sum total of human happiness by making “Cattle population (head) (2005)” available on its website, above and beyond FAO’s contribution? I’m really hard put to say. The datasets are easier to use in Google Earth from FAO’s website than in any format provided by IFPRI, in my opinion. And the basic analyses available in Mappr will probably be useful to some, sure, but since sharing the map itself is tricky from there, you still have to got to FAO for that.

So the poor user probably has to navigate at least two separate and quite different websites to get all she needs. One wonders whether the donors behind all of these different efforts to provide data on cattle population numbers around the world (if indeed there were more than one, apart from the aforementioned Gates Foundation) considered that before green-lighting the projects. And, of course, that’s just cattle numbers. Life is just way too short for me to plough through all the other datasets at HarvestChoice looking for overlaps like these, but I’d be willing to bet this is not an isolated example. We know that crop distribution data is also out there in all sorts of different places, forms and formats. And, in fact, there’s some evidence of balkanization in other types of livestock data too. I’m not saying it’s hell out there for spatial data in agriculture, on a par with Genebank Database Hell. But it is definitely a bit of a jungle.

Does it matter? I don’t know. Maybe the users of these types of data really like having multiple websites to visit for downloading and visualization. Maybe the funds involved in developing all these different datasets and websites are minimal anyway. I’d really like to hear from the people involved at HarvestChoice, FAO and ILRI (are there other players?). But is there even a forum in which these guys meet to discuss data issues? Because if there were, and I by some miracle were to be invited to it, what I would say is that what I would prefer is a single place to go for cattle population numbers maps and the like (e.g. crop production data), with lots of options for exporting the raw data for use in my own GIS, the ability to import and combine my own datasets online, and some elegant ways of sharing the results. 1 That, for me, would be value for money. And I can’t believe I’m alone in that.

Mapping nutrition research

The Leverhulme Centre for Integrative Research on Agriculture and Health (www.lcirah.ac.uk) and the University of Aberdeen are embarking on an interesting project for the UK’s Department for International Development.

The objective of the project is to map the growing research activity on agricultural interventions to improve nutrition in low-middle income countries and identify “gaps” in current and anticipated research.

You might like to consider contributing information if you are undertaking or planning research with a

focus on an interaction between agriculture and nutrition, such as agricultural interventions to improve nutrition and their evaluation, the influence of agricultural practices and food value chains on nutrition, governance and policy processes through which agriculture and nutrition are linked, and links between agricultural productivity and/or growth and nutrition at a macro scale etc.

The people to contact are Corinna Hawkes (corinnahawkes “at” o2.co.uk) and/or Rachel Turner (rachel.turner “at” lshtm.ac.uk). It could be your research, or research you know about. Or indeed relevant networks (mailing lists, online fora, communities of practice) you participate in.

No doubt someone will eventually mash up the results with all the clever maps now available on HarvestChoice‘s recently revamped website.

The cutting-edge MAPPR, for example, enables users to pick and choose among hundreds of “layers” of map-based information about all aspects of smallholder agriculture in Africa—from poverty to rainfall—and make customized maps and summary tables.

But more on that tomorrow. Stay tuned…

LATER: It occurs to the blogger, belatedly, that “to map” has more than one meaning. Ooops.

Brainfood: Bee diversity, Fodder innovation, African agrobiodiversity, Quinoa economy, Fragmentation and diversity, Rice in Madagascar, Rice in Thailand

- Management increases genetic diversity of honey bees via admixture. No domestication bottleneck there!

- Enhancing innovation in livestock value chains through networks: Lessons from fodder innovation case studies in developing countries. Fodder innovators of the world, organize. If you don’t, you will lose your value chains.

- Introduction to special issue on agricultural biodiversity, ecosystems and environment linkages in Africa. Special issues? What special issue?

- The construction of an alternative quinoa economy: balancing solidarity, household needs, and profit in San Agustín, Bolivia. Despite the allure of fancy denominations of origin and the like, old-fashioned cooperatives, and the much-maligned intermediary, manage to hang on in there.

- Species–genetic diversity correlations in habitat fragmentation can be biased by small sample sizes. Can.

- The original features of rice (Oryza sativa L.) genetic diversity and the importance of within-variety diversity in the highlands of Madagascar build a strong case for in situ conservation. Actually the way I read it, the stronger case is for ex situ. But see what you think.

- Population structure of the primary gene pool of Oryza sativa in Thailand. In situ Strikes Back.