The Arnold Arboretum has a nifty new app which lets you access information about individual plants right on your mobile phone as you walk around the grounds. And that of course includes lots of crop wild relatives…

The Arnold Arboretum has a nifty new app which lets you access information about individual plants right on your mobile phone as you walk around the grounds. And that of course includes lots of crop wild relatives…

Feral or relict: you decide

What do you call an escaped agricultural plant? I ask because two recent items have made me wonder. Exhibit A, a Zester Daily article entitled Wild Apple Adventure. Naturally I conjured up scenes of derring do in the mountains around Almaty. How disappointing, then, to discover that Zester’s version of “wild” is actually “feral,” apple trees that have either survived the orchard around them or else are seedlings growing in the wild.

Exhibit B, a recent announcement on a mailing list of a meeting on Nordic Relict Plants. 1 I’d always thought of relicts as leftovers from massive ecological changes, like relict rain forests, or relict pockets of pre-ice age flora. But no …

This meeting is for everyone with an interest in relict plants, particularly but not exclusively, in Nordic and Arctic areas. By a relict plant we mean a plant species or variety that was, but is no longer, cultivated in a particular place, and has survived in that place after cultivation stopped. These plants are important parts of our cultural history and can sometimes contain genetic material that is different from more modern varieties of the plant.

So, what should one call these plants? Wild, to me, sounds wrong. Feral, most dictionaries I consulted agree, suggests both “not domesticated or cultivated” and “having escaped from domestication”. To which at least one helpfully adds “having escaped from domestication and become wild,” which is surely not true of erstwhile crops.

I rather like “relict”. What do you think?”

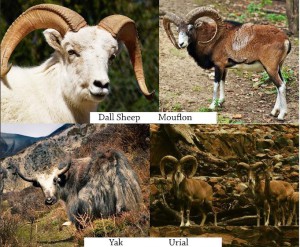

Highest altitude sheep

The Biodiversity Heritage Library has this nice montage on its Facebook page, where it asks the question: “Which of the species pictured here lives at the highest altitude of all grazing herds?” You can vote here. I think the answer is the only non-wild sheep of the four, but it could be a trick question.

The Biodiversity Heritage Library has this nice montage on its Facebook page, where it asks the question: “Which of the species pictured here lives at the highest altitude of all grazing herds?” You can vote here. I think the answer is the only non-wild sheep of the four, but it could be a trick question.

Prospects for fish (and other) farming

The CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems launched recently with this video of what research can do for poor families in Bangladesh, and yes, they’re big on agricultural biodiversity. All they need to do now is stop sea-levels rising …

Rewarding excellence in Indian rice breeding

India’s Directorate of Rice Research has just recognized the Paddy Breeding Station of Tamil Nadu Agricultural University (TNAU) as the best rice breeding station among India’s 107. The Vice-Chancellor of the university said that:

“The landmark varieties that have been developed through Pure Line Selection by this station triggered the growth of rice production in the State. The first variety — GEB 24 (Kichili Samba) — released during 1921 played a significant role in the development of rice cultivars over the years, not only in India, but world-wide.”

With help from the irrepressible Nik and his local version of IRRI’s all-knowing germplasm database we can actually kind of quantify that. It turns out that out of the 11 IRRI releases in 2011 (IR155-165), only IR157 (an irrigated japonica) doesn’t have GEB 24 in its pedigree. Just for that, it would seem to be a very well-deserved award. But I’m also told they helped IRRI build up its collection in the early days.

What about the other direction of use, though? Well, IR8 starts to feature, by itself, in the pedigrees of TNAU varieties in the early 70s (e.g. in CO38 and CO40), then by the early 80s there are 5 IRRI lines involved in the development of CO43. But by the 90s there are a couple dozen IRRI lines in the pedigree of CO47. So the flow of germplasm has been two-way.

In more ways than one. Apparently, IRRI are in the process of restoring to TNAU some of their CO varieties, which they had lost for one reason or another, but had taken the precaution of sending to Los Baños. Good collaboration all around. Great to see the achievements recognized in the popular press, if not necessarily the collaboration. But then that’s what we’re here for.

LATER: Further delving into the database by our friends at IRRI reveals that TNAU sent material quite regularly to IRRI from 1961 to 1987, with a peak of 952 accessions in 1978. But “only 40% of TNAU’s CO varieties conserved in the IRRI genebank came directly from TNAU. 30% came via CRRI and 30% via other organizations. TNAU obviously shared their material widely.”