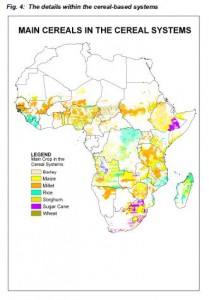

It’s over a year old, but I’ve only just learned about the ILRI publication “A production system map for Africa.” Looks interesting. I’ll just reproduce here the map showing the extent of different cereal-based system, with the main species involved. Looks like Angola is the most cereal-diverse country in sub-Saharan Africa. As with all such maps, one (or at least I) longs to plonk the locality of germplasm accessions on top of it. And to know how they relate to other crop maps produced by the CGIAR system.

It’s over a year old, but I’ve only just learned about the ILRI publication “A production system map for Africa.” Looks interesting. I’ll just reproduce here the map showing the extent of different cereal-based system, with the main species involved. Looks like Angola is the most cereal-diverse country in sub-Saharan Africa. As with all such maps, one (or at least I) longs to plonk the locality of germplasm accessions on top of it. And to know how they relate to other crop maps produced by the CGIAR system.

Mashing up banana wild relatives

Over at the Vaviblog is a detailed discussion (though not nearly as detailed as the paper) of a new paper outlining a new theory for the origin of the cultivated banana. 1

Edible bananas have very few seeds. Wild bananas are packed with seeds; there’s almost nothing there to eat. So how did edible bananas come to be cultivated? The standard story is that some smart proto-farmer saw a spontaneous mutation and then propagated it vegetatively. Once the plant was growing, additional mutants would also be seen and conserved. In fact this “single-step domestication” is considered the standard story for many vegetatively-propagated plants, such as potato, cassava, sweet potato, taro and yam. And while it may be true for those other crops, evidence is accumulating that it may not be the whole story for bananas.

Leaving the details aside, De Langhe and his colleagues propose that instead of a single step, at least two were involved, with a proto-cultivated banana back-crossing with one of its wild relatives and then being seen by the proto-farmer as an improvement to be added to her proto-portfolio of agricultural biodiversity. Something very like that is going on today among cassava farmers, for example; they allow volunteer seedlings, the product of sexual reproduction between already favoured clones and wild relatives, to flourish in their fields and then select among them. 2 Banana farmers could easily have done the same.

To quote again from The Vaviblog:

The big question, of course, is “what does any of this matter?”. And the surprise is that it really does. Banana breeding is difficult at the best of times; no seeds, no pollen, you can imagine. But if the backcross hypothesis is true, then the current approach to banana breeding, which De Langhe et al. describe as “substituting an A genome allele by an alternative derived from a AA diploid source of resistance or tolerance to biotic and abiotic stress”, might be misguided. If the chromosomes are not “pure” A or B, and if backcrosses were involved in the origin of banana varieties, maybe breeders should look again at some of the diploid offspring from their crosses and see whether they could be further backcrossed to come up with types that are more use to farmers.

Now, what I really need is for one of the handful of people who really understand this stuff to tell me where I’ve misunderstood it.

Orange sweet potato not a “magic bullet”

They are no magic bullet, but next to a more diverse diet, they may prove to be the most cost-effective approach to reducing hidden hunger.

This statement may well be something of a breakthrough, which is why I think it deserves some prominence here. In the battle against malnutrition there has long been a general needless opposition among supplements, biofortification (by genetic engineering and conventional breeding) and dietary diversity. Each has its place, and if we are highly biased towards dietary diversity, it is because we think it is the most sustainable option, with plenty of spin-off benefits. To hear IFPRI and HarvestPlus suggest that orange-fleshed sweet potatoes may actually be less cost effective than dietary diversity in fighting malnutrition is music indeed.

Coconut conservation dilemma de-horned

Remember the Polymotu Project, that intriguing new approach to conserving coconut genetic resources? Well, it is making progress, at least with the so-called “horned coconut.” Read all about it on Roland Bourdeix’s blog.

Remember the Polymotu Project, that intriguing new approach to conserving coconut genetic resources? Well, it is making progress, at least with the so-called “horned coconut.” Read all about it on Roland Bourdeix’s blog.

Share Fair set fair to share

The “AgKnowledge Africa Share Fair” is off and running at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Addis Ababa, and will continue until 21 October. You can follow proceedings in all sorts of web 2.0 ways, detailed on the blog. There’s no specific “learning pathway” on agrobiodiversity, but that’s ok, there’s still plenty of interest to us here. Including a “food fair” which will focus on “sharing the indigenous/local content embedded in African food.” Wish I was there for that!