![]() One of the arguments in the organic-can-feed-the-world oh-no-it-can’t ding dong is about the total yield of organic versus non-organic. 1 Organic yields are generally lower. One reason might be that, with a few exceptions, mainstream commercial and public-good breeders do not regard organic agriculture as a market worth serving. The increase in yield of, say, wheat over the past 70-80 years, which has been pretty profound, has seen changes in both agronomic practices — autumn sowing, simple fertilizers, weed control — and a steady stream of new varieties, each of which has to prove itself better to gain acceptance. Organic yields have not increased nearly as much. A new paper by H.E. Jones and colleagues compares cultivars of different ages under organic and non-organic systems, and concludes that modern varieties simply aren’t suited to organic systems. 2

One of the arguments in the organic-can-feed-the-world oh-no-it-can’t ding dong is about the total yield of organic versus non-organic. 1 Organic yields are generally lower. One reason might be that, with a few exceptions, mainstream commercial and public-good breeders do not regard organic agriculture as a market worth serving. The increase in yield of, say, wheat over the past 70-80 years, which has been pretty profound, has seen changes in both agronomic practices — autumn sowing, simple fertilizers, weed control — and a steady stream of new varieties, each of which has to prove itself better to gain acceptance. Organic yields have not increased nearly as much. A new paper by H.E. Jones and colleagues compares cultivars of different ages under organic and non-organic systems, and concludes that modern varieties simply aren’t suited to organic systems. 2

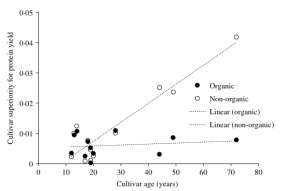

The basics of the experiment are reasonably simple. Take a series of wheat varieties released at different dates, from 1934 to 2000. Plant them in trial plots on two organic and two non-organic farms for three successive seasons, measure the bejasus out of everything, and see what emerges. One of the more interesting measures is called the Cultivar superiority (CS), which assesses how good that variety is compared to the best variety over the various seasons. As the authors explain, “A low CS value indicates a cultivar that has high and stable performance”. The expectation is that a modern variety will have a lower CS than an older variety, and for non-organic sites, this is true. At organic sites, the correlation is much weaker.

You can see that in the figure left (click to enlarge). For the open circles (non-organic) more modern varieties have lower CS (higher, more stable yield), while for filled circles (organic) there is no relationship. Why should this be so. Because of those changes in agronomic practices mentioned above.

You can see that in the figure left (click to enlarge). For the open circles (non-organic) more modern varieties have lower CS (higher, more stable yield), while for filled circles (organic) there is no relationship. Why should this be so. Because of those changes in agronomic practices mentioned above.

[M]odern cultivars are selected to benefit from later nitrogen (N) availability which includes the spring nitrogen applications tailored to coincide with peak crop demand. Under organic management, N release is largely based on the breakdown of fertility-building crops incorporated (ploughed-in) in the previous autumn. The release of nutrients from these residues is dependent on the soil conditions, which includes temperature and microbial populations, in addition to the potential leaching effect of high winter rainfall in the UK. In organic cereal crops, early resource capture is a major advantage for maximizing the utilization of nutrients from residue breakdown.

To perform well under organic conditions, varieties need to get a fast start, to outcompete weeds, and they need to be good at getting nitrogen from the soil early on in their growth. Organic farmers tend to use older varieties, in part because they possess those qualities. Concerted selection for the kinds of qualities that benefit plants under organic conditions, which tend to be much more variable from place to place and season to season, could improve the yileds from organic farms.