![]() The Crop Science paper by Mark van de Wouw, Rob van Treurena and Theo van Hintum 1 of the Centre for

The Crop Science paper by Mark van de Wouw, Rob van Treurena and Theo van Hintum 1 of the Centre for

Genetic Resources, the Netherlands (CGN) probably deserves more than the rather cryptic Nibble we gave it yesterday. It certainly seems to be eliciting some interest in the media.

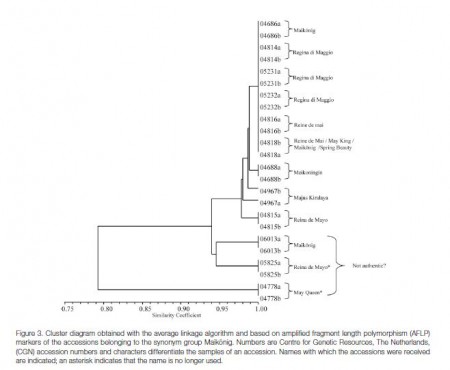

What van de Wouw and friends did was look in detail at alleged duplicates in a collection, the Dutch collection of old lettuce cultivars to be precise. I say alleged because when the researchers DNA fingerprinted plants from accessions which by all rights should have been identical, they weren’t. Known duplicates turned out to be unknown something elses. About 20% of accessions with the same cultivar name (out of a total of 283 accessions in 124 name groups) were in fact significantly different at the DNA level, and they shouldn’t have been. So, for example, 3 of the 12 accessions labelled Maikönig (or similar) in the collection are probably no such thing:

Lettuce is inbreeding, and “[d]iversity within accessions and accidental crossing is not a major issue for cultivars of a self-pollinating crop…” The researchers therefore blame “mislabeling and seed contaminations during processing and handling of the accessions,” mostly “from the period before uptake in the CGN collection.” Better procedures and better documentation systems now exist, and similar problems are much less likely, at least in properly run genebanks.

But what to do with the existing errors? Just remove the erroneous name from the database? Or get rid of the seeds too?

Removing the seeds might be the preferred option, as maintaining a collection is a costly operation and funds are limited… However, if the nonauthentic accession has been extensively evaluated and shown to have valuable characteristics it might be worthwhile to keep the accession, without the cultivar name, in the collection, provided it is confirmed that the accession was already nonauthentic at the time the evaluations were performed. Alternatively, a seed sample could be reacquired in case authentic material is still available elsewhere.

Was it all worth it? Does the significance of this study go beyond the fact that some accessions of old lettuce cultivars in the Dutch genebank may have got mixed up in the past? Well, there are 7.4 million odd accessions in the world’s genebanks, but they’re not all different. Some have no duplicates at all, others dozens. Maybe only about 2 million are unique. That adds to costs, so it would be worthwhile getting rid of a few duplicates. But only if they are in fact truly duplicates, and can easily be identified as such. As the cost of genotyping declines, detecting duplicates (at least in inbreeders and vegetatively propagated species) is becoming cheaper than maintaining them. That may be the most important message to take home from this thought-provoking paper.

- Wouw, M., Treuren, R., & Hintum, T. (2011). Authenticity of Old Cultivars in Genebank Collections: A Case Study on Lettuce Crop Science, 51 (2) DOI: 10.2135/cropsci2010.09.0511

In a perfect world, genebanks would recieve large original samples that would be tested for duplication upon their arrival. These samples would be accompanied by complete passport data and all this information would be stored in a database that could be accessed by genebanks around the world. In reality, funding is lacking to do the comaprisons needed to eliminate duplications. Also, cultivar names used as a determiner of duplication can be problematic. Did they come from similar donors? Has selection occured during the existance of that cultivar. In other words, a sample of seed is donated and at the genebank it’s genetic profile is maintained as a snapshot with no selection presure. The same cultivar or landrace continues to exist in the real world and some selection occurs that makes it better suited for the enviroment it is grown in – is it still the same? Has the genetic profile been altered? Does it still carry the same cultivar name. Does this count as a duplicate accession?