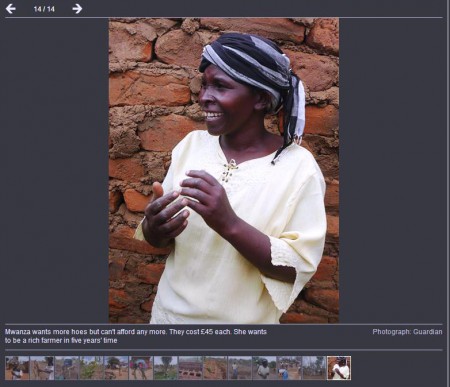

This post is not really about agricultural biodiversity, but I think it is worth stretching a point on some occasions. Take a look at the caption for this photograph. It’s the last in a gallery from The Guardian which goes with a nice write-up of what sounds like a very worthy Farm Africa project.

Forty-five pounds for a hoe? Forty-five pounds? I must say I’d missed that when I first went through the photos, but when Jeremy pointed it out I had to admit that seemed a bit steep for a hoe.

Well, is it just us? What do we know about the price of hoes in Kenya, right? Internal evidence in the article suggests that £45 is a lot of money, but a fair price for a hoe.

But low-tech can still be costly. Mwanza says she would like more hoes, but at £45 a hoe, it is far more than she can afford. The simple brick house she lives in with one of her children is no bigger than a small bedroom.

But googling comes up with a much cheaper price in Uganda:

“A hoe is a very cheap thing. It costs Shs 7,500 each and when I buy one it can last more than two years,” Nyakoojo said.

That would be about £1.70. And when the wife sent text messages to everyone she could think of in Kenya she got back figures closer to the Ugandan than The Guardian. A very fancy hoe goes for about KSh 1,200, or £8, we were told.

So what’s going on? Normally, I’d probably just dismiss it as a misplaced decimal point somewhere. Or perhaps a misunderstanding about what exactly the tool involved is. But it appears that this “hoe” is the weapon of choice in the Manichean fight against GMOs.

Small African farmers such as Mwanza stand on the frontline in the battle for higher productivity and agricultural development, a struggle being fought not with tractors and GM crops but with hoes, wheelbarrows and indigenous drought-resistant crops: cowpeas, pigeon peas, green grams, sorghum and millet.

So I think we should all be extra clear about what one costs. Starting with The Guardian. And the Gates Foundation.

This could be a misprint and-or misunderstanding on the part of the writer? Though, even at the ‘correct’ price, hoes can be a major investment for poorer smallholders. That is the case here in Burundi, where a hoe may be shared by several families and is often included as part of an agricultural ‘package’.

In the 19th century in central-east Africa, economic transactions were frequently carried out with hoes.