![]() David Spooner and co-workers have written a comprehensive overview of the systematics and genetics of wild and cultivated potato species (Solanum section Petota) ((Spooner, D., Ghislain, M., Simon, R., Jansky, S., & Gavrilenko, T. (2014). Systematics, Diversity, Genetics, and Evolution of Wild and Cultivated Potatoes The Botanical Review, 80 (4), 283-383 DOI: 10.1007/s12229-014-9146-y)). This nicely illustrated and very accessible paper is essential reading for anyone interested in potato diversity — or indeed the study of plant diversity in general.

David Spooner and co-workers have written a comprehensive overview of the systematics and genetics of wild and cultivated potato species (Solanum section Petota) ((Spooner, D., Ghislain, M., Simon, R., Jansky, S., & Gavrilenko, T. (2014). Systematics, Diversity, Genetics, and Evolution of Wild and Cultivated Potatoes The Botanical Review, 80 (4), 283-383 DOI: 10.1007/s12229-014-9146-y)). This nicely illustrated and very accessible paper is essential reading for anyone interested in potato diversity — or indeed the study of plant diversity in general.

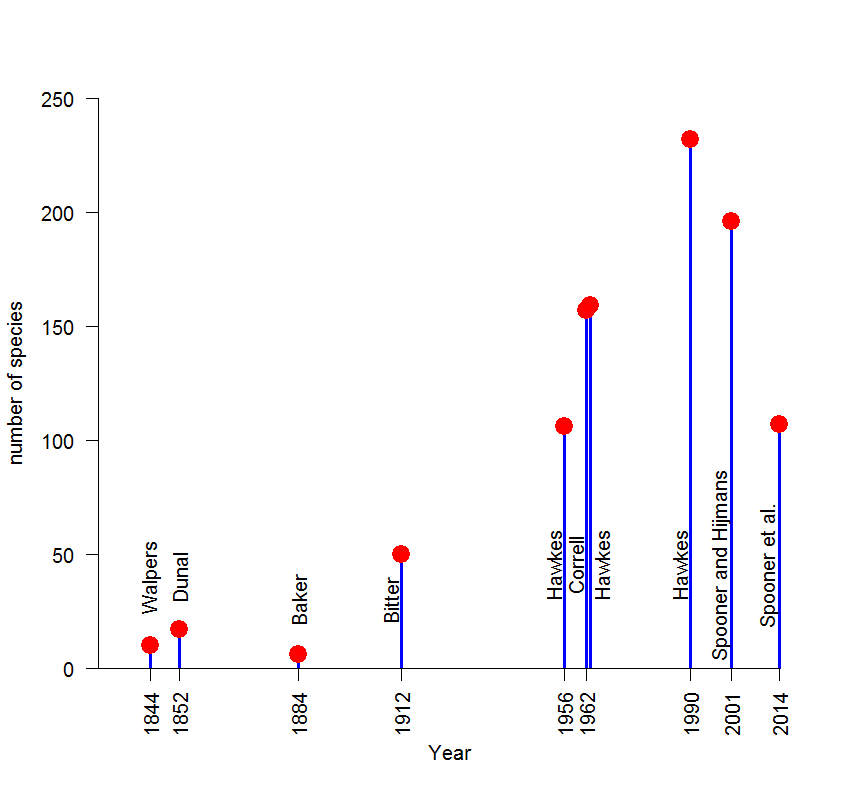

A remarkable aspect of wild potato systematics is the way the number of recognized species has fluctuated over time. In 1956, Hawkes recognized 106 species, but in his 1990 treatment of the group this had increased to 232. This will likely be the highest number we’ll see, because it has come down drastically since, and Spooner et al.’s paper puts it at 107 — almost exactly where it was back in 1956. This does not mean that we are back to the same set of taxa though. Many new species were described after 1956, notably by Carlos Ochoa, who named about 25% of the 107 species. ((Ed.: Our thanks to Dr Spooner and his co-authors for linking to the obituary of Carlos Ochoa we published on this blog. I think this marks the first time the blog has been referred to in a peer-reviewed paper.))

The graph below shows the number of species over time, based on published compilations, and the name of the authors ((This is an update of a figure in the now somewhat obsolete Atlas of Wild Potatoes.)) .

It is not easy to determine where a wild potato species begins and where it ends. Many species look very similar, and there is “lack of strong biological isolating mechanisms and the resulting interspecific hybridization and introgression, allopolyploidy, a mixture of sexual and asexual reproduction, and recent species divergence.” A smaller number of species is not necessarily better, but, in the case of wild potatoes, Spooner et al. think it will help us move away from “a taxonomy that is unnatural, unworkable, and perpetuates variant identification” to a system that hopefully enables better conservation and use of these plants.

It also creates a mess, though, because previous analyses based on species level diversity, for example to set collection and conservation priorities, may need to be revised. Spooner et al. update some of the analysis of geographic pattern in wild potato species richness described previously.

The reduction in the number of species is in large part due to new insights from David Spooner’s incessant work on this group, through molecular and morphological studies, and observations during collecting expeditions. His kind of naturalist is a species that is also declining in numbers, or so it seems. That is not a good thing, as there is a lot of work to do.

Thank you Robert for an informative and nice review. David Spooner.

A pleasure, David. When will the carrot one be ready? :)