There’s a document on the NordGen website entitled Towards a European Plant Germplasm System — The third way 1 which advocates setting up a “European Plant Germplasm System” along the lines of the US National Plant Germplasm System. Written by Lothar Frese, Anna Palmé, Lorenz Bülow and Chris Kik — all from big European genebanks — the paper “builds on the results of the PGR Secure project funded under the EU Seventh Framework Programme.”

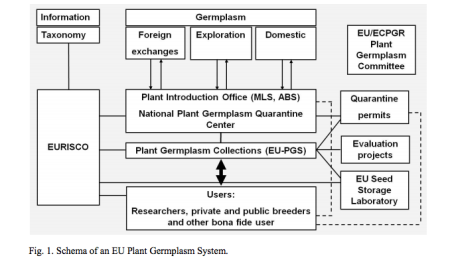

This is what the European system would look like:

What, no Svalbard? Even the NPGS uses that. Also, there are separate germplasm committees for each crop in the US, rather than one committee to rule them all. That makes more sense if the idea is to have input from the users, as in the US; but maybe that’s not it, as in the diagram the committee is not linked to the users. So what is it for? Anyway, how much would this all cost?

As a rule of thumb, the ex situ conservation including related research costs approximately 60 € / accession and year (personal communication of Dr. U. Lohwasser of 23 May, 2014 and Dr. P. Bretting of 22 May 2014). 1,725,315 accessions are kept in European genebanks resulting in an assumed total annual costs for ex situ conservation of 103,518,900 € per year for the whole of Europe. In view of the 34 billion € spent for agri-environmental measures within the EU-28 a budget of 100 million € / year is not unreasonable. The question rather is whether the stakeholder groups and policy makers feel that having a European Plant Germplasm System is worth this amount.

Well, let’s fact-check that. The operating budget for the NPGS is $44,600,000 per year, for 569,000 accessions, which is about $78 per accession, or about €70 at today’s exchange rate. That’s probably a conservative estimate, I’m reliably informed, as the NPGS gets a lot of in-kind support from the universities with which it cooperates — but it’s the right ballpark anyway. The international genebanks of the CGIAR get around $20 million a year to maintain and make available their ca. 700,000 accessions, which seems very cheap, but includes very little of those “related research costs.”

What we don’t know — or at least I don’t — is what European countries are actually spending on their genebanks at the moment. It seems maybe the authors don’t know either, because another of the 12 recommendations they make, besides establishing the system, is to inventory the money available. Here are all the recommendations, conveniently filleted out for you. Look at number 6:

1. We suggest the establishment of a European Plant Germplasm System.

2. Establish a legal basis for conservation of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture in the EU.

3. Establishment of a technical EU infrastructure for the organisation of conservation of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture measures.

4. Establishment of an EU information infrastructure for conservation of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture.

5. Disentangle juridically and financially genebank tasks from plant breeding research and plant breeding tasks at the national level.

6. Inventory of financial means available to genebanks and estimation of financial means needed for a fully functioning European network of genetic resource collections (ex situ, in situ and on-farm).

7. Increase the visibility of plant genetic resources collections on the internet.

8. Develop a European platform for long-term crop specific pre-breeding programmes.

9. Clear uncertainties concerning Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) rules so that breeding companies can take economic decisions on a safe legal basis.

10. Research should be strengthened to better understand the amount and geographic distribution of genetic diversity present in priority crop gene pools.

11. The European agro-NGOs and their influence should be strengthened.

12. Establishment of a European Network of Private-Public-Partnership programmes for evaluation of plant genetic resources in Europe.

My own recommendation would be to start with that inventory of financial means. It would be nice to know how close to that €100 million we in fact are — and how much of it, if any, would need to be new money.

There is — of course — a section on in-situ, both on-farm and for crop wild relatives. I am getting seriously worried about the current fashion for in-situ conservation of landraces in contact with crop wild relatives (for example, lots of the projects of the ITPGRFA benefit-sharing fund). Unless the risks of crop failures and wider plant disease epidemics are fully understood and managed these projects could lead to disaster and loss of farmers’ livelihoods.

As an example, the conclusion of a paper on wild Helianthus pathology in North America (where they know what they are doing):

Does anybody seriously want `breeding sanctuaries of virulent races’ as a result of these phenomenally ill-advised projects? There are more effective and safer ways of identifying and utilising resistance that don’t threaten farmers.

Europe apart, my considered opinion is that farmers in developing countries cannot handle the responsibility for controlling the mess that could result.