This analysis does not attempt, in any manner, to undermine the significance of the exotic germplasm material received by India during the course of time, irrespective of the source. India is a recipient of a large amount of germplasm over the period of time from multiple donors including CG genebanks and other national genebanks.

That, you may possibly remember, is from a paper on the flow of genebank material out of India. Our commentary on that paper also brought into play a compilation of data by researchers at Bioversity which quantified the movement of germplasm from India and other countries not only outwards into the CGIAR genebanks, but also in the other direction. This turned out to be just as extensive. But, of course, national programmes like India’s do not just benefit from the CGIAR genebanks through the direct access they have to the material they conserve. They also benefit from the crop improvement programmes of CGIAR centres, which churn out breeding lines and varieties using the raw materials found in their genebanks, and make them freely available to national breeders.

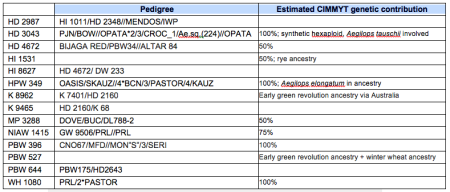

We actually saw an example of that recently when India published a list of drought and flood resistant varieties of various crops that had just been released. Through the magic of Wheat Atlas, and some expert knowledge, for both of which we’re very grateful, we can actually work out the contribution of, say, CIMMYT, to the wheat varieties on that list. Here it is, at a first, rough approximation:

Along the same lines, a recent blog post from IRRI says that

Seventy percent of all varieties released in the Philippines were strongly linked with IRRI between 1985 and 2009.

I’m sure India, and the Philippines, would agree that those international genebanks, and the crop improvement programmes they feed, are well worth having. Maybe even worth paying for.