Yes, I’m fully aware that you’re fed up with examples of how complex and time-consuming plant breeding is, and how reliant it is on material in genebanks being available in perpetuity. I can hear you saying it from here: “We get it, already; move on.” But it’s my blog, not to mention my job, so here’s another one.

You may have seen news of the identification of a gene in rice that the authors of a recent paper in PNAS think holds promise for significantly increasing yields. I won’t speculate here about whether that hope will be fulfilled, or indeed whether theirs was the best strategy to follow. I just want to illustrate what it took to get to the point of being in a position to thus speculate. Here’s the background, from the introduction section of the PNAS paper: it goes back over 20 years:

In 1989, a breeding program for New Plant Type (NPT) rice was launched at IRRI to increase the yields of modern indica cultivars by using genetic material from tropical japonica landraces. Several Indonesian tropical japonica landraces — which are characterized by large panicles, large leaves, a vigorous root system, thick stems, and few unproductive tillers — have been used in international breeding programs. However, despite these features, the NPT cultivars yield less than modern indica cultivars, mainly because of low grain fertility and low panicle number. To genetically dissect and elicit the valuable traits of NPT cultivars, we backcrossed the NPT cultivars … against modern indica cultivar IR64 to develop introgression lines (ILs) (Fig. S1). BC3-derived ILs, which had favorable yield-related traits and few undesirable traits, were selected by field observation. …a near-isogenic line (NIL)…, derived from tropical japonica landrace Daringan with an IR64 genetic background, had more spikelets per panicle and more branches than IR64.

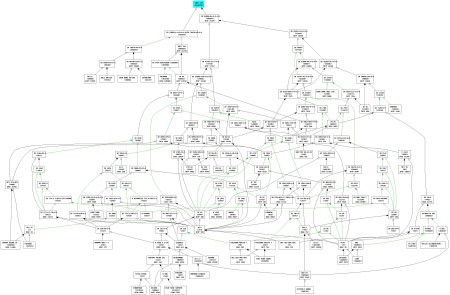

Here’s what that looks like, from the supplementary materials of the paper (it’s that Fig. S1 mentioned in the snippet quoted above):

That’s a lot of work. Let’s recap. First there are the various plant lines that came out of the NPT project, which in themselves were the result of a lot of work. Then there was the crossing of those to IR64, and various generations of backcrossing (that’s all those BCs) to end up with different plants in which different bits of the tropical japonica genome are embedded into what is mainly the IR64 indica genome. Then one of those bits of tropical japonica genome had to be found to improve IR64. That came from a particular landrace from Indonesia, called Daringan. 1 Which, of course, the authors found in the IRRI genebank, though they don’t actually say so, unfortunately. Phew.

Quick digression here into Genebank Database Hell. It turns out that if you look at the relevant databases at IRRI, 2 you can’t in fact prove to 100% certitude that the sample of Daringan used by the breeders in question in this work came from the IRRI genebank. There’s a gap in the chain of data, due to the fact that by and large genebanks and breeders use different documentation systems, or used to. Everybody currently working at the genebank knows that the seeds came from them. Problem is, what happens when they go? They really need to correct the data in their documentation system, which almost uniquely at IRRI now covers both genebank accessions and breeding materials. But who wants to fund correcting data in a database? Anyone who wants to see genebanks serve breeders’ needs effectively and efficiently into the far future, thats who.

Anyway. Ok, so after all that, now the gene has been isolated and it, and it only, has been inserted into one of the newer indica varieties, IRRI 146, with promising results. But wait, it’s not over, because IRRI 146 is itself far from a simple thing. Here is its pedigree, courtesy of IRRI’s database. You can click on it to see it better, if you dare.

So each incremental step in breeding, each of the advances that the press likes to hype as a breakthrough, actually relies on building on all the painstaking genetic reshuffling work that came before, going back decades in many cases, with the occasional infusion of new diversity from genebanks, as in the case of Daringan. We may have this gene now, and I hope it does lead to those hoped-for increases in yield when it finally gets into farmers’ fields, but you know we’re going to need another one soon, and then another one. 3 We always do. And we’re going to get them from seed which is sitting in a genebank. We hope.

It’s not that the breeders and genebank used different documentation systems, rice breeders (perhaps more than any other group I encountered in 40 years of PGRFA work) were/are reluctant to record/use genebank accession numbers. There seems to be this perspective (myth even) that one genebank accession with such-and-such a name is the same as another with the same name. This is clearly NOT the case as we showed time and time again. It should be possible to trace when IRRI breeders received the accession in question of ‘Daringan’ from the genebank data system, but not whether it was this source of seeds that were used. I hope that with a revamp of IRRI’s breeding strategy (not held back by the hierarchical dominance of previous head breeders) that this situation will change. This lack of germplasm accession identification (which Ruaraidh Sackville Hamilton and I have posted about before) has serious implications for other areas of rice science if different groups have used different rice accession with the same name. The genome research using Nipponbare comes to mind, where (if my memory serves me correctly) different labs have come up with different results – presumably because they used a different seed source. It’s one explanation anyway, and I’m sticking to it!

Mike of course you are right, when a breeder just puts “Daringan” in the pedigree, we can’t be sure it’s from the genebank, even if we can be sure the genebank gave Daringan to the breeder. That’s what’s behind Luigi’s “100% certitude”. In this case, we know that we gave them Daringan just as they were planning the hybridization block in which they made the cross. Good enough evidence? What’s the likelihood that they asked for and got seed for their hybridization block and then chose to use a different seed source? Presumably very low, but still debatable.

What is not debatable is that we need to stop future recurrence of such uncertainties. We could get away with them in the old days, but not now with the new technologies as well as the new politics.

The Sub1 gene story is also a two decade one – but its deployment in Asian mega-varieties in flood-prone areas is already having a significant impact in eastern India and Bangladesh. Fortunately the Gates Foundation is also supporting the down stream work on dissemination and adoption as well as the basic research.

Would it be a reasonable argument that as breeding progresses in major crops, then less and less commonly do genebank samples contribute to parentage? In pedigrees it seems that most recent parents/predominant are breeding lines or formal bred varieties that may neither be conserved in genebanks, nor covered by the FAO Seed Treaty, nor stored in Svalbard. If so, then the greatest value in germplasm may be breeders’ working collections and therefore the greatest threat to future food security may be the loss of these collections through neglect, retirement, closing of breeding programmes, changing fashions (agroecology?) or as yet unknown issues. Perhaps contentious: without breeding programmes, genetic resources are almost useless and without breeders’ varieties/work in progress human numbers would fall below 3 billion. Fund-raising slogan: “Conserve a breeder”.

Dave – you make a very valid point. However there are some breeders I would NOT conserve. :-)

Seriously though, when I was teaching grad students at Birmingham in the 80’s we had this motto: ‘No conservation without use’. Let’s not conserve for the sake of conservation ending up with museum collections, which has been the approach of some. Conservation per se is important of course. But how many genebank collections have been thoroughly evaluated and used. Thank goodness for the CGIAR efforts in this respect with genebank collections alongside breeding programs, although even as I encountered when I first joined IRRI there were formidable barriers between the genebank and the breeders. It just came down to personalities. Some of the attitudes and stories would make your toes curl. But we did succeed in making the collection more open to the world.

If you allow me to contribute to this discussion, I’d like to say the following, as a non-germplasm specialist and non-breeder. Although it is always very interesting trying to trace back all those origins and one should make every effort to record such things, it is also clear that it becomes increasingly ambiguous to do so. Breeders use many donors and they also constantly generate new materials and mix many things up on purpose. Take for example the huge efforts we now have in IRRI on creating MAGIC populations. So, there is always going to be difficulties trying to piece things together, but my main point is that in the end what counts most for us is the product, not necessarily knowing all of its origins down to the last piece. I fully agree with Dave Wood’s statement, but would modify the last sentence by saying that we must concentrate much more on ensuring that we conserve the materials and data of a breeder, knowing that we can’t quite conserve a person beyond a certain age. That is one of the key reasons for why we are now implementing a whole new breeding information management system at IRRI as a single, corporate system.

Many thanks for your message. Tracing back origins is more than just “interesting”, however. It is essential in making the case for continuing support to genebanks. And it is required by the ITPGRFA.

Luigi: I think we need to see support for genebanks and breeding programmes as fused at the hip functionally. Most if the value of genebanks comes from plant breeding sensu lato, then demonstrating value results specifically from incorporating bits of genebank samples in useful varieties. And about sample origin being required by the ITPGRFA: this only dates from 2004 and samples moved before this are not retrospectively covered. Daringan seems to have been used long ago – for example, in Japan. Also, if the sample came post-Treaty from IRRI it would be covered by an SMTA (IRRI has the very best systems for tracking SMTAs). I suggest that if there is no SMTA then its supply by IRRI either pre-dated the Treaty or the breeders sourced the sample from non-IRRI, non-Treaty sources: if so then Treaty requirements do not apply. Further, surely the point about the `multilateral’ Treaty is that origin is not just not `interesting’ but immaterial – it’s all in the same pot (or not, if it is sourced outside the Treaty). If a sample is useful and from a genebank (as Daringan almost certainly was), then that alone merits support for genebanks. The Treaty has changed nothing for the better in support for genebanks compared with the pre-Treaty system. Some – me included – argue that the Treaty has seriously messed-up the old system of access and benefit-sharing from and for developing countries (and almost certainly encouraged the non-attribution of country of origin for useful samples).

Let me return to my main point – which has nothing to do with the Treaty and traceability from a legal point of view – which is, whether we like it or not, the reality of the germplasm world we work in.

My concern about traceability – and I take Achim to task here as he admits being a ‘non-breeder/non-germplasm specialist’ – is that knowing the origin of a piece of germplasm is VERY important from a genetic and pedigree point of view. I’ve seen some of the difficulties that have arisen because breeders were using germplasm with the same name that clearly were not the same genetically. I had an argument with Gurdev Khush about the status of one of the IR varieties being grown today, and other samples that had been put in the genebank under the same name. They were clearly not the same. And the material that Gurdev insisted was the correct IR variety (i.e. what was being grown now), and that any rice breeder would recognise, was not the same as the sample of that variety that had been placed in the genebank when the IR variety was first released, maybe a couple of decades earlier. Same goes for Nipponbare, Azucena – widely used materials in genetics research – but not all the same.

Might need some comment from IRRI on this: While the original use of Daringan (and lots of other landraces with names but not genebank numbers) was in the early 1990s New Plant Type programme the subsequent research published in the 2013 PNAS paper was on the resultant breeding line IR68522-10-2-2. And this has been distributed under an SMTA (SMTA2012-0661). As Daringan at the time of use in the early 1990s was not in the ITPGRFA (nor covered by the CBD) it would seem uncertain if IRRI breeding lines using it should be covered by an SMTA. My advice would be to keep as much as possible outside the Treaty until it is clear that the Treaty is working- to be evidenced by masses of samples coming out of (say) Brazil, India, and Ethiopia. Putting everything in throws away a massive bargaining chip for the institutions holding valuable breeding lines and also provides undeserved support for the until-now flawed Treaty.

I accept Mike’s point about confusion over varieties. A numbered and documented genebank sample should be the `type’ (a technical term taken from plant taxonomy where an actual designated herbarium specimen typifies the species/variety or whatever rank).