What I should have mentioned in my recent post on online information resources for wheat varieties, as Jeremy then pointed out to me, is that those linkages between the different databases that I was hoping for are going to be much easier to make and maintain if we had a system of digital object identifiers (DOI) in place for wheat varieties. A DOI is a string that specifies a unique object within a particular system. The object could be a scientific publication. Or indeed a scientist. It is probably about time we implemented such a system for genebank accessions in general, and crop varieties in particular. No?

Mashing up the Global Forest Disturbance Alert System

So here’s how I’d like that Global Forest Disturbance Alert System I blogged about a couple of day ago to work, eventually. Or even this. Or this, for that matter.

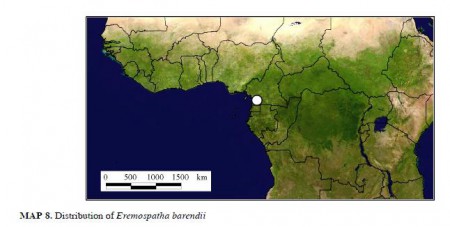

But anyway. Say you’re reading about rattans in West Africa and you get interested in, say, Eremospatha barendii, which is kind of rare and probably perhaps sort of endangered, maybe. So you head on over to GBIF to get a better idea of its geographic distribution, but you come up blank. But then you do some more digging and you realize that there’s a new taxonomic revision, describing in minute detail the morphology and ecology of all the African species, with nice drawings and lists of specimens and identification keys. 1 And, by golly, it has pretty maps too.

Pretty, but unusable. The damn things are in a PDF, not the nice Google Earth files you would have got from GBIF. But the coordinates of all the specimens 2 are given in the text, so you extract them from the PDF and plonk them into Google Maps. It’s the little green arrow in southern Cameroon shown below.

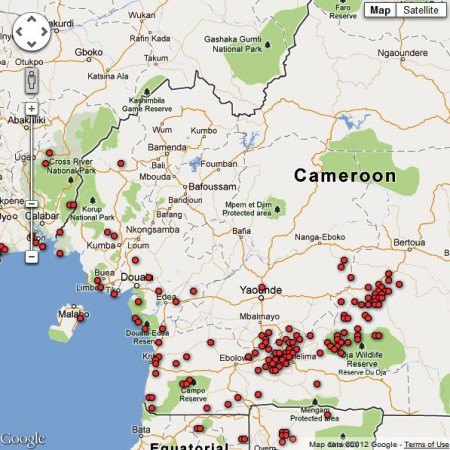

But you also want to know to what extent that area is threatened. So you head on over to the Global Forest Disturbance Alert System and you look at the latest data on where there is forest disturbance happening in Cameroon, which are the little red dots here.

Now you can see if that population of yours is perhaps threatened. Well no, you can’t do that now, not easily, because there’s no way to export the little red dots to Google Maps, or import the little green arrow into the Global Forest Disturbance Alert System. But I’m sure you will be able to do that one day. And then you could actually visit 3.066667 N 10.716667 E, and check out that Eremospatha barendii population, assuming it is still there, what with you spending so long mashing up the data and all, and also ground-truth any disturbance that the Global Forest Disturbance Alert System might have, er, alerted you to; maybe even describe its causes. And annotate the little green arrow and the little red dots with your observations.

Wouldn’t that be nice?

Nibbles: Maize genome, Mapping plants in the US, Sixth extinction, Finding species, Korean dog, IUCN guidelines, Ginkgo evolution, Churro sheep, Malaysian trees, Nutrition training

- Maize diversity sliced and diced to within an inch of its life.

- Mapping invasives sometimes = mapping crop wild relatives. Compare and contrast.

- Red List hits 20,000 species.

- And yet we keep finding new ones, even in Europe.

- Reconstructing a Korean dog breed.

- You too can help IUCN with its genebank guidelines.

- Video history of ginkgos. “Are we watching them as they evolve, or are they watching us?”

- Video history of Navajo sheep. Touching.

- Malaysian forest tree genebank at work. Any ginkgos in it?

- Hurry! You have 2 days to apply for a Training course on Food Systems: From Agronomy to Human Health, in Benin.

Brainfood: Agronomy, Endophytes, Breadfruit morphology, Setaria genetic diversity, Yeast epigenetics, Wild rice

- Avenues to meet food security. The role of agronomy on solving complexity in food production and resource use. Wait, what, it’s not all about the breeding?

- Population studies of native grass-endophyte symbioses provide clues for the roles of host jumps and hybridization in driving their evolution. Wait, what, we have to conserve these things too now?

- Morphological diversity in breadfruit (Artocarpus, Moraceae): insights into domestication, conservation, and cultivar identification. Cool, we now have a multi-access Lucid key to help us recognize varieties.

- Geographical variation of foxtail millet, Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv. based on rDNA PCR–RFLP. Geographic differentiation, centre in East Asia, evidence of migration, yada yada.

- Within-genotype epigenetic variation enables broad niche width in a flower living yeast. Wait, what, now we have to document the epigenome too?

- Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon: a genome-wide view. Fancy markers come through where lesser breeds caused confusion. Two groups, clinally arranged, with the China-Indochina group close to indica, neither close to japonica. So one, Chinese, domestication event, yada yada.

Agricultural biodiversity and population in Laos

Normally, I would elegantly link some trenchant comments on the Agrobiodiversity Initiative in the Lao PDR (TABI), whose website has recently been pointed out to us, 3 to the equally recent release of the AsiaPop dataset. But Lao PDR is, annoyingly, not (yet?) one of the countries for which AsiaPop has spatial population data. Which is a pity because TABI does have some interesting-looking maps on its study sites as well as a rather more forbidding, though no doubt extremely useful, online metadata platform.

Failing that, I’ll just leave you with TABI’s own description of TABI:

TABI is a long term commitment by the Lao Government and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) which seeks to conserve, enhance and manage the biological diversity found in farming landscapes in order to improve the livelihoods of upland farm families in northern Laos. During its first phase (2009-2012) TABI is geographically focusing on Luang Prabang and Xieng Khouang Provinces in the north of Laos.