You may remember I blogged from a conference in Amman over a year ago. It was about how climate change would affect food security in the dry areas. Well, the conference proceedings has been out for a while, courtesy of ICARDA, but I only just found out about it. Lots of interesting stuff in there. Thanks, Colin.

To split or not to split

![]() Usually when I notice a paper that might be of interest to a particular constituency what I might do is write a post and then send the link to those people and try to get them to comment on it on this blog. With variable results. So with “Managing self-pollinated germplasm collections to maximize utilization” by the USDA’s Randall L. Nelson I tried something different. 1 I emailed the link to the paper itself, with a very brief introduction, to the managers of the CGIAR genebanks and a few others, asking them what they thought of its recommendations. And what I’ll do here is give you their responses. 2 And maybe start a wider discussion.

Usually when I notice a paper that might be of interest to a particular constituency what I might do is write a post and then send the link to those people and try to get them to comment on it on this blog. With variable results. So with “Managing self-pollinated germplasm collections to maximize utilization” by the USDA’s Randall L. Nelson I tried something different. 1 I emailed the link to the paper itself, with a very brief introduction, to the managers of the CGIAR genebanks and a few others, asking them what they thought of its recommendations. And what I’ll do here is give you their responses. 2 And maybe start a wider discussion.

But let’s start at the beginning. What does the paper say? Using the USDA Soybean Germplasm Collection as a case study, it makes the case for maintaining germplasm of self-pollinated species as pure lines rather than as originally collected, i.e. as heterogenous seed lots. Nelson thinks this latter, “historically standard” strategy, aimed at maintaining maximum diversity, essentially “unworkable”. And a brake on use.

Heterogeneous accessions are in constant risk of change and loss. It is possible to mitigate the risk factors, but they can only be lessened and not eliminated. Maintaining pure-lined accessions for self-pollinated species not only eliminates the problems associated with genetic drift and natural selection, but also enhances the accuracy of the evaluations and fosters effective germplasm utilization. Neither the current potential to characterize entire germplasm collections with tens of thousands of DNA markers nor the future potential of whole genome sequencing to completely characterize the diversity of all accessions in collections can be fully realized for self-pollinated species unless accessions are homogeneous and homozygous.

It really comes down to this:

It is not practically possible to accurately describe a heterogeneous accession. When seed contamination occurs, it is highly unlikely that it will be recognized and remedied, and, no matter what precautions are taken to ensure seed purity, accidental seed contamination or mislabelled seed lots will occur in large germplasm seed collections.

And without accurate descriptions, no use. The solution: “pure-lining” each accession:

At maturity, multiple single plants are harvested to represent each identified phenotype. The following year, each plant row is again characterized, and each row with a different phenotype is harvested and added as a new accession. Rows that are segregating are discarded based on the assumption that these rows are the product of a recent cross pollination and both parents would be available.

There are drawbacks, of course. Selecting on phenotype means you can miss genotypic variation. But the advantage of more efficient use trumps this.

Although there is a risk that the pure lines will not preserve all of the variation in the original sample, this risk occurs once, and then the integrity of each accession can be economically and predictably maintained forever. Genetic drift and natural selection are not factors in compromising the integrity of the accession, and accidental seed contamination can be detected and removed because each accession has a precisely known description.

So how common is this management strategy in other genebanks? First, it should be pointed out that this is a problem that genebank managers have been grappling with for quite a while now. Ehsan Dulloo of Bioversity International called for compromise:

In revising the FAO/IPGRI genebank standards currently being done, this issue has come up. Some think it is impractical to maintain separate accessions, while others think that it is good to maintain them separately. Further, collections of wild populations are also sometimes divided by maternal lines to increase use and is a recommended practice. I think that as far as possible genebanks should strive to manage their accessions into purelines accessions … since this improve use as shown in the article. But they should also keep their original accession as an entity and this can be useful for restoration work.

Such a mixed approach seems to be common. Tom Payne of CIMMYT agrees that pure-lining can enhance use.

Some of the heterogeneous populations maintained in the CIMMYT-held wheat collection are maintained as disaggregated pure lines. One set of materials, in particular, are the Mexican “sacramental” wheat landraces collected by Bent Skovmand & Julio Huerta in the mid-1990s. As the article states, access and utilization to these characterized pure breeding lines has been enhanced through this practice.

According to Ahmed Amri…

…[t]his is a common practice at ICARDA. We have maintained some pure lines as separate accessions only when they are received as such like durum lines from Iran and Ethiopia received from USA and Italian collaborators. We are also including the pure lines extracted from a landrace when it is proven to have a given use after selection from the original population. There was an effort in the past on selecting pure-line from faba bean populations and ICARDA is still maintaining both the original populations and the pure-lines from them.

David Tay followed a similar approach in his former job at AVRDC.

When I was at AVRDC I maintained the soybean and mungbean as pure lines when proven so. If an accession segregates then it was maintained as bulk.

Ruaraidh Sackville Hamilton quoted a paper from 2002 that sets out a decision tool for combining or splitting accessions. The practice at IRRI is rather different.

If we can identify discrete sub-groups, we do a trial seed increase with separate sub-groups. If they breed true, keep separate. If they segregate, recombine. I think this is discussed in Van Hintum et al. from about 10 years ago.

And Hari Upadhyaya sounded a definite note of caution.

At ICRISAT we maintain germplasm of self-pollinated crops in their original forms, without changing their composition. In case of the landraces which are heterogenous (and heterozygous also), it would be very expensive exercise to divide the landraces as pure lines following seed, plant, agronomic, and other traits. We have more than 70% landraces, and they do have heterogeneity. Dividing each of them in to landraces using different criteria based on traits, the number would be staggering. Also, even when, we think we have separated them into pure lines, we will not be sure unless carry for few generations and confirm based on morphological traits or using markers. This would be too expensive. Number also (considering at least 5-10 pure lines per landraces) would become many fold in each genebank, resulting into lack of resources to safely conserve, characterize, evaluate for enhanced use. Our main focus should be on enhancing use of these resources.

So is maintaining pure-lines something that breeders should do, rather than genebanks? Well, maybe, but Toby Hodgkin decided to start a hare about that.

Not to start a hare but, from a breeders point of view, one might be better creating a few MAGIC type populations running them to fixation and then using these as sources of variation (gets rid of all that obsession with accessions and the need to maintain them in some imperfect way!). Of course this doesn’t deal with the need to maintain traditional varieties as they were collected to meet future needs of those who provided them — but that’s a different aspect.

Ok, so there you have it. This is what the practice on pure-lining is in the international genebanks of the CGIAR Centres. What do you do in your genebank? Or, as a breeder or other user, what would you prefer the genebanks you rely on for your raw material to do?

Climate change and PGRFA discussed, and discussed again

Jeremy and/or Andy will no doubt correct me if I’m wrong, because they’re there and I’m not, but I believe it is the very presentation embedded below that was made a matter of only minutes ago by our friend and colleague Andy Jarvis of CIAT at the Special Information Seminar on CLIMATE CHANGE AND GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE: STATE OF KNOWLEDGE, RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES at FAO. How’s that for timeliness. If not, then Andy will probably give it at the CGRFA-13 side event on pretty much the same subject on Tuesday. Or maybe both? No online sign of the other presentations yet, but I’ll get the scoop on the event from the boys this evening, I expect.

More on those Azeri buffaloes

Thanks to Elli from the Save Foundation for this comment on our recent post on water buffalo in Azerbaijan.

They were crossed with Murrah in Soviet times, just like in the Ukraine and Bulgaria. I’m just preparing a report on Buffalo in SE Europe and we’ve been looking at the situation in Georgia too.

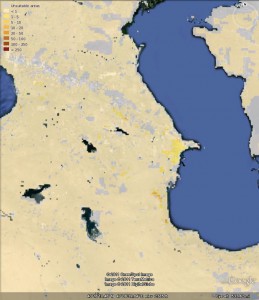

Good to know. Incidentally, I should have mentioned another source of livestock information on the previous post: Gridded Livestock of the World (GLW). If you squint, 3 you can just about make out that it does show some buffaloes in Azerbaijan and other countries in the southern Caucasus.

Good to know. Incidentally, I should have mentioned another source of livestock information on the previous post: Gridded Livestock of the World (GLW). If you squint, 3 you can just about make out that it does show some buffaloes in Azerbaijan and other countries in the southern Caucasus.

Nibbles: Breeding, Frankincense and myrrh, Roman pills, Chinese botanic garden, NPGS, Green red bush tea, Old banyan, Terroir, Botanic gardens and invaders, AnGR

- National Organic Coalition suggests USDA’s National Institute for Food and Agriculture separate conventional and participatory breeding from anything involving DNA in considering projects for support.

- Second-guessing the Three Wise Men.

- Yet more on attempts to deconstruct ancient Roman medicines using DNA from tablets found in a shipwreck. Real Indiana Jones stuff.

- Botanic garden and genebank for drought-resistant plants to be established “in Asia’s largest wild fruit forest.” That would be in China. I really don’t know what to make of this. Really need to find out more. But why am I talking to myself?

- Brown (rice) is beautiful.

- Feedback from a genebank user. Kinda.

- Rooibos gets itself certified.

- The oldest cultivated tree on record.

- The taste of Massachusetts.

- “…strongly conservation-minded botanic gardens appear to be in the minority.” Easy, tiger. Will that new one in China (see above) feature in this minority?

- ILRI on an Aussie TV program on conserving local livestock breeds in Africa.