- Another day, another tree disease threatens the British landscape.

- Some Swedish trees are not doing too well either.

- Seeds of Trade. A virtual book at the NHM. Lots of info on the history of crops.

- What are the pollination needs of a particular crop? FAO will tell you if you ask nicely.

- Purple tea in Kenya. Luigi’s mother-in-law not impressed.

Taro on Facebook

The very Web 2.0 savvy John Cho is at it again. He’s got more great historical pictures of Hawaii and its taro culture on his personal Facebook page. And he’s started to post about his breeding work on a separate Facebook page dedicated to Colocasia esculenta. ((How many other crop pages are there? I need to find out, but how?)) If you’re into taro in any way, you need to become John’s friend.

Nibbles: Microlivestock, Urban ag, Ag info, School meals in Peru, Agrobiodiversity indicators, Nature special supplement, Extension, Breeding organic, Forgetting fish in China, Deforestation, Russian potatoes, Fijian traditional knowledge, Megaprogrammes

- FAO slideshow on Egyptian rabbits.

- Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development calls for papers on urban agriculture. Will some look at the intersection with art?

- And IAALD re-launches its journal.

- “…students receiving online encouragement from the national soccer star reported going to bed at night looking forward to receiving their iron supplements the following morning.” Great, of course. But why not iron-rich foods?

- Speaking of which, there’s a new FAO publication on “Foods counting for the Nutritional Indicators Biodiversity.” No, I don’t quite understand it myself. Something to do with what foods count towards CBD biodiversity targets. Well, it’s the International Year of Biodiversity, after all.

- Indeed it is. And Nature makes the most of it. See what I did there? No agriculture though, natch.

- Extension gets a forum?

- Biotech can be useful in organic farming? Say it ain’t so!

- More evidence of shifting baselines in people’s perceptions of biodiversity. How quickly they forget.

- Will they forget what forests look like?

- The Vavilov Institute potato collection needs a thorough going over. Taxonomically, that is.

- Making salt in mangrove ponds in Fiji. Nice video. Not agrobiodiversity, but it’s my blog and I like seeing Fiji on it.

- CGIAR abandons agrobiodiversity? Say it ain’t so. Anyone?

- Speaking of megaprogrammes, there’s going to be one on agricultural adaptation to climate change, right?

- “So, how does huitlacoche taste? Does it matter?? LOOK AT IT! I guess it would be fair to say it doesn’t taste as truly horrible as it looks. The flavor is elusive and difficult to describe, but I’ll try: ‘Kinda yucky.'” Don’t believe him! And read the rest.

What are breeders selecting for?

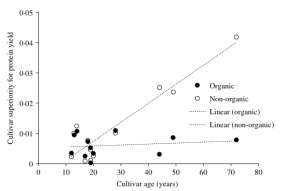

![]() One of the arguments in the organic-can-feed-the-world oh-no-it-can’t ding dong is about the total yield of organic versus non-organic. ((For want of a suitably non-judgemental term.)) Organic yields are generally lower. One reason might be that, with a few exceptions, mainstream commercial and public-good breeders do not regard organic agriculture as a market worth serving. The increase in yield of, say, wheat over the past 70-80 years, which has been pretty profound, has seen changes in both agronomic practices — autumn sowing, simple fertilizers, weed control — and a steady stream of new varieties, each of which has to prove itself better to gain acceptance. Organic yields have not increased nearly as much. A new paper by H.E. Jones and colleagues compares cultivars of different ages under organic and non-organic systems, and concludes that modern varieties simply aren’t suited to organic systems. ((JONES, H., CLARKE, S., HAIGH, Z., PEARCE, H., & WOLFE, M. (2010). The effect of the year of wheat variety release on productivity and stability of performance on two organic and two non-organic farms The Journal of Agricultural Science, 148 (03) DOI: 10.1017/s0021859610000146))

One of the arguments in the organic-can-feed-the-world oh-no-it-can’t ding dong is about the total yield of organic versus non-organic. ((For want of a suitably non-judgemental term.)) Organic yields are generally lower. One reason might be that, with a few exceptions, mainstream commercial and public-good breeders do not regard organic agriculture as a market worth serving. The increase in yield of, say, wheat over the past 70-80 years, which has been pretty profound, has seen changes in both agronomic practices — autumn sowing, simple fertilizers, weed control — and a steady stream of new varieties, each of which has to prove itself better to gain acceptance. Organic yields have not increased nearly as much. A new paper by H.E. Jones and colleagues compares cultivars of different ages under organic and non-organic systems, and concludes that modern varieties simply aren’t suited to organic systems. ((JONES, H., CLARKE, S., HAIGH, Z., PEARCE, H., & WOLFE, M. (2010). The effect of the year of wheat variety release on productivity and stability of performance on two organic and two non-organic farms The Journal of Agricultural Science, 148 (03) DOI: 10.1017/s0021859610000146))

The basics of the experiment are reasonably simple. Take a series of wheat varieties released at different dates, from 1934 to 2000. Plant them in trial plots on two organic and two non-organic farms for three successive seasons, measure the bejasus out of everything, and see what emerges. One of the more interesting measures is called the Cultivar superiority (CS), which assesses how good that variety is compared to the best variety over the various seasons. As the authors explain, “A low CS value indicates a cultivar that has high and stable performance”. The expectation is that a modern variety will have a lower CS than an older variety, and for non-organic sites, this is true. At organic sites, the correlation is much weaker.

You can see that in the figure left (click to enlarge). For the open circles (non-organic) more modern varieties have lower CS (higher, more stable yield), while for filled circles (organic) there is no relationship. Why should this be so. Because of those changes in agronomic practices mentioned above.

You can see that in the figure left (click to enlarge). For the open circles (non-organic) more modern varieties have lower CS (higher, more stable yield), while for filled circles (organic) there is no relationship. Why should this be so. Because of those changes in agronomic practices mentioned above.

[M]odern cultivars are selected to benefit from later nitrogen (N) availability which includes the spring nitrogen applications tailored to coincide with peak crop demand. Under organic management, N release is largely based on the breakdown of fertility-building crops incorporated (ploughed-in) in the previous autumn. The release of nutrients from these residues is dependent on the soil conditions, which includes temperature and microbial populations, in addition to the potential leaching effect of high winter rainfall in the UK. In organic cereal crops, early resource capture is a major advantage for maximizing the utilization of nutrients from residue breakdown.

To perform well under organic conditions, varieties need to get a fast start, to outcompete weeds, and they need to be good at getting nitrogen from the soil early on in their growth. Organic farmers tend to use older varieties, in part because they possess those qualities. Concerted selection for the kinds of qualities that benefit plants under organic conditions, which tend to be much more variable from place to place and season to season, could improve the yileds from organic farms.

Nibbles: Rice, Tamil Nadu genebank, Seed Day, Olives, Nordic Cattle, Marmite, Musa, Butterflies, Congo

- Japonica rice heads for the tropics for first time.

- Yet another Indian genebank opens its doors.

- And from somewhere else in India, we are alerted to the fact that today is International Seed Day.

- The biggest little olive farm in the world? Texas virgin on sale.

- Old endangered Norwegian cattle more efficient than modern breed. Genetics too.

- Foods, words, politics — a heady brew.

- Banana vs plantain. Jeremy says: Someone is wrong on the internet.

- Butterfly farming in Kenya under the spotlight. Again.

- Launch video of the expedition down the Congo river; agriculture only a pretty backdrop.