- The preservation of genetic resources of the vine requires cohabitation between institutional clonal selection, mass selection and private clonal selection. Intra-varietal diversity, that is. They apparently do it best in Portugal.

- Association of dwarfism and floral induction with a grape ‘green revolution’ mutation. Cool things I learned from this paper: 1. Pinot Meunier is a periclinal mutant. 2. Tendrils are inflorescences. 3. Dwarf grapes are dwarf for the same reason dwarf wheat is dwarf. No word on what the Portuguese are doing about it. And the fact that the paper is over 10 years old is irrelevant to its coolness.

- Quantifying the impacts of ecological restoration on biodiversity and ecosystem services in agroecosystems: A global meta-analysis. Supporting ecosystem services go up 40% on average, regulating ES by 120%. Well worth having.

- Can a Botanic Garden Cycad Collection Capture the Genetic Diversity in a Wild Population? Yes, but need to “(1) use the species biology to inform the collecting strategy; (2) manage each population separately; (3) collect and maintain multiple accessions; and (4) collect over multiple years.” Maybe they should talk to the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden guys.

- Genebanking Seeds from Natural Populations. It’s more difficult than with crops. And then you’ve got the above.

- Genomics-assisted breeding for boosting crop improvement in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan). “…pigeonpea has become a genomic resources-rich crop and efforts have already been initiated to integrate these resources in pigeonpea breeding.” And now we wait.

- Crop wild relatives of pigeonpea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.]: Distributions, ex situ conservation status, and potential genetic resources for abiotic stress tolerance. 15 of them need collecting. And, presumably, genotyping (see above).

- Diversity in the breadfruit complex (Artocarpus, Moraceae): genetic characterization of critical germplasm. 349 individuals from 255 accessions are 197 unique genotypes from 129 lineages.

- Musa spp. Germplasm Management: Microsatellite Fingerprinting of USDA–ARS National Plant Germplasm System Collection. Used to identify mislabelled in vitro accessions. Data in GRIN-Global.

- Education and access to fish but not economic development predict chimpanzee and mammal occurrence in West Africa. Having fish to eat means you leave chimpanzees alone.

- Community Perspectives on the On-Farm Diversity of Six Major Cereals and Climate Change in Bhutan. About 30% of varieties lost over last 20 years. But what does it mean that “93% of the respondents manage and use agro-biodiversity for household food security and livelihood”? What exactly does that other 7% of farmers do?

- Amino acid composition and nutritional value of four cultivated South American potato species. S. goniocalyx is best for you. But does it taste any good?

Setting the rules of the game

We’re delighted to publish today a guest post from Gabi Everett. Gabi is an MSc student in Cristobal Uauy’s research group at the John Innes Centre. We hope this is the first of many contributions from her. Until the next one, though, you can follow her on Twitter.

I’ve never been one to listen much to the radio, but having started working with cereals in the last couple of months, I decided to tune in to BBC4 the other day to hear The Grain Divide, a program about wheat. From hearing about the team of scientists who died of starvation during World War 2 instead of eating their seed collection, to a farmer so driven to recreate a heritage bread that he’s dedicated his life to it, all of the stories had something in common: people passionate about our crop’s diversity.

Many people around the world today have the same interest and passion (although in maybe a less poetic way), and a lot of effort is being put into conserving this diversity in seedbanks and other forms of germplasm collections. With 7 million accessions worldwide (of which around 2 million are thought to be distinct), we are faced with the question: how do we make the most of them?

To fully unlock the potential of genetic resources — to discover new useful traits and breed new and adapted crop varieties — the genotypic and phenotypic variability of these collections has to be better understood. This information isn’t available today in a systematic global manner, and this is the gap that the DivSeek initiative hopes to fill.

An international effort with a diverse set of enthusiastic stakeholders, DivSeek hopes to define the best way to do germplasm evaluation, by putting genomics and phenomics at the service of breeders: “omics” shouldn’t scare anybody off. The DivSeek partners want to create standards and tools for handling data that will transform large-scale germplasm evaluation into a much more effective and systematic process.

The first difficulty to be overcome is that there isn’t a single genotyping method that caters to all needs. The objectives of genotyping germplasm can range from assessing overall genetic variability, to finding rare alleles, carrying out population studies, and creating prediction models that relate genotype to phenotype. For each purpose, different genomic tools can be used, with different pros and cons (nicely reviewed here). Added to this, some crops are better served with genomic resources than others. In the end, a number of methods will have to be standardized, which will take time.

Another issue regards standardizing phenomics for wild species. Wild relatives do not in general have an environmental range as big as that of the crop. To make sure that a trait identified in a wild relative at one site is stable and of agronomic importance at other sites too, it should be assessed across this larger distribution. A solution would be to cross the wild relative to a number of elite varieties. While this might be ok on a small scale, scaling up will put a lot of strain on resources, both human and data.

Another challenge will be making sure that the information produced has a long life span. This is especially difficult when considering how new technologies appear at an ever increasing rate these days, and how the challenges faced by farmers change over time. Large-scale phenotyping is likely to be carried out for numerous traits over a long period, which means that it needs to be done in a way that allows for comparison between different projects and collections.

Some of the challenges that I want to see addressed by DivSeek is how to be inclusive of minor crops and how to engage smaller seedbanks. It is expected that major crops, with more genomic resources and money behind them, will be exhaustively studied in evaluation efforts. It is also expected that seedbanks that are already involved in such projects will continue to be engaged. I am looking forward to seeing how the work done by DivSeek on major crops will impact on the potential of smaller collections and minor crops. Maybe the existence of a structured pipeline will be a positive influence.

Last week I had the chance to meet a representative from a DivSeek partner from the UK — this brought home to me again the strength of DivSeek, which is its diversity of players and their passion and enthusiasm for the initiative. From seedbank managers, to bioinformaticians, breeders and researchers, I hope this diversity is maintained and strengthened.

My hope for the future of the initiative is that it succeeds not only in creating a standardized framework for the management of phenotypic and genotypic evaluation data, but that this leads to a change in how collections and genetic variability are seen outside the genebank community. It might not be too much to hope for that the success of DivSeek in getting the most out of crop collections will have a positive impact on how plant and environmental conservation in general are valued.

Target 2.5 passes muster

By 2020 maintain genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants, farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species, including through soundly managed and diversified seed and plant banks at national, regional and international levels, and ensure access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge as internationally agreed.

Sound familiar? Well, it is Target 2.5 of the draft Sustainable Development Goals, contributing to the goal to

End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.

It’s not exactly as I would personally prefer to phrase it, but you know what it’s like, this language wasn’t just crafted by a committee, but by a committee of committees.

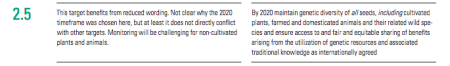

Anyway, despite whatever stylistic shortcomings the language of this particular target may have, it has just received a seal of approval by the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the International Social Science Council (ISSC) in their recent review of the SDGs as they currently stand. This is what the report has to say about 2.5 in particular:

Very sensible suggestions for improvement. For the record, I think the 2020 timeframe was chosen to gel with the Global Plant Strategy for Plant Conservation. Anyway, overall, the target is “well defined and based on the latest scientific evidence,” unlike 71% of the other 168. Phew.

Nibbles: Species modelling vids, Diverse farm, MAIZE, Maize, COP20, Scuba rice, Trad food, Siberian Svalbard

- A niche modelling course on YouTube.

- Diversify for better nutrition.

- Cool infographic for CGIAR’s maize work.

- Which doesn’t mention the 58 names of maize.

- Discussion on genetic diversity from the first day of the Global Landscapes Forum 2014, in Lima, Peru, during COP20. And more from same thing, scroll down.

- Scuba rice in Bangladesh.

- Supporting food traditions in Sudan and Oklahoma.

- More on that weird, unnecessary, Siberian seed vault.

Building a European Plant Germplasm System

A couple of days ago we blogged about a study by European genebankers which recommended the establishment of a “European Plant Germplasm System” (EPGS) along the lines of the US National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS). Let’s see how far the analogy can be pushed.

Some of the key features illustrated in the diagram of the “EPGS” provided in the paper, and reproduced in our post, are: active germplasm collections, a central seed storage laboratory, a system-wide information system and a plant germplasm committee. There are some interesting differences between the European and US versions of each of these. The constituent European germplasm collections, for example, would be the national collections, which tend to have a very wide range of species; whereas in the US some at least of the individual germplasm repositories are fairly focused on a crop or group of similar crops. That makes for efficiencies. Or would all the “small grains” in Europe end up in one national genebank, and all the apples in another, as in the US?

Another difference, as we discussed in the previous post, is the nature of that European plant germplasm committee. There is supposed to be only one of these in Europe, whereas in the US there is one per crop, to provide guidance and advice from germplasm users to the crop curator. That to me makes more sense.

As for information systems, Eurisco is not at the moment comparable to GRIN. The NPGS uses GRIN (GRIN-Global in the near future) to both manage workflows within the genebank and make some of the resulting data available for searching on the internet. Eurisco does only the latter at the moment (and, incidentally, like GRIN, serves its data up to Genesys). But then I expect the individual European genebanks are quite happy with their various data management systems and don’t necessarily need to share a single, standardized system. Or do they?

Perhaps the biggest difference, however, is with the central seed storage laboratory. There is at present no European Ft Collins at all to provide safety duplication of seed accessions. It would have to be built from scratch. Or perhaps one of the bigger national genebanks could suck in safety duplicates and morph into a regional genebank? But is a single central repository really necessary at all? What if, instead, you had different national genebanks taking regional responsibility for safety duplication of different crops? This would not be a new idea by any means, though I don’t think it’s ever been implemented anywhere in the world. Might it be an option in Europe?

Then there’s the stuff that’s not on the diagram. Take coordination mechanisms. The NPGS has biennial face-to-face meetings of all genebank curators, with teleconferences in the “off-years.” Plus there’s national–level coordination by the ARS Office of National Programs. The National Plant Germplasm Coordinating Committee coordinates and communicates information among federal, state and other funding entities. A related issue is administrative structure. NPGS genebanks are budgeted in a ARS Research Project, which is funded by an annual Congressional appropriation. This in turn contributes to ARS National Program 301 (Plant Genetic Resources, Genomes, and Genetic Improvement). Every five years, each National Program and its constituent Research Projects undergo external reviews. After that, each Research Project writes a new Project Plan for the next five years for review. What would European coordination and administration on crop genetic resources look like? Some is already provided by the European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Resources (ECPGR), of course. Would ECPGR’s processes and structures — not to mention funding — be sufficient for a European Plant Germplasm System?

So. I guess the bottom line is that it’s easy to say that it would be nice to have a European version of the US National Plant Germplasm System. But then you start to drill down into what that would actually mean, and lots of options open up at each turn. And, at each turn, whether it makes sense to do it in Europe exactly like they do it in the US will, as they say, depend.