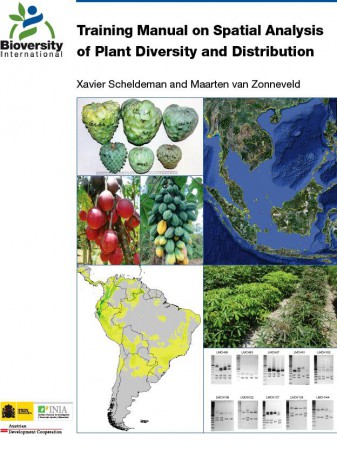

Great to see “Training Manual on Spatial Analysis of Plant Diversity and Distribution” finally out, courtesy of Bioversity International. Well worth the wait, and not just because I get called a pioneer in it. Congratulations to Xavier Scheldeman and Maarten van Zonneveld for addressing a very important need.

Great to see “Training Manual on Spatial Analysis of Plant Diversity and Distribution” finally out, courtesy of Bioversity International. Well worth the wait, and not just because I get called a pioneer in it. Congratulations to Xavier Scheldeman and Maarten van Zonneveld for addressing a very important need.

This manual has been published as a result of the increasing number of requests received by Bioversity International for capacity building on the spatial analysis of biodiversity data. The authors have developed a set of step-by-step instructions, accompanied by a series of analyses, based on free and publically available software: DIVA-GIS, a GIS programme specifically designed to undertake spatial diversity analysis; and Maxent, a species distribution modelling programme. The manual does not aim to illustrate the use of each individual DIVA-GIS and Maxent command/option, but focuses on using GIS tools to help answer common questions relating to the spatial analysis of biodiversity data. Throughout the manual, the importance of proper sampling is stressed; however, it is beyond the scope of the document to elaborate on sampling theories. The manual also does not discuss the statistical analysis of diversity data in detail; instead, when statistical methods and programmes are mentioned in the text, the reader is referred to alternative reference materials for further information.