Long-time readers may remember a post from 2012 summarizing some media reports of trouble at the Italian national genebank at the National Research Council (CNR), Bari. But maybe things are not as bad as were made out at the time. Or have got better.

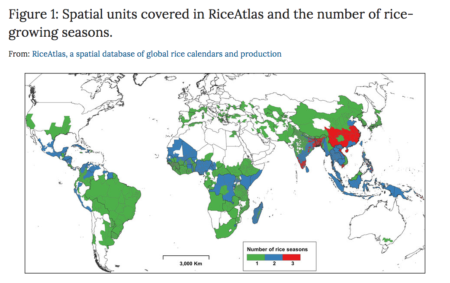

I’ve just come across what seems to be a fairly new website for the genebank and it doesn’t give the impression of crisis. It lists 57,568 accessions from 184 genera and 834 species, which is more that was reported back in 1999 in WIEWS for ITA004, hopefully the correct code for the genebank in question (at least the address matches, if not the name of the institute). This is the geographic coverage of the collection:

Impressive. Unfortunately, data on these accessions are not available in the European genebank database, Eurisco, and therefore they’re not in the global portal, Genesys, either. Hopefully that’s being rectified.

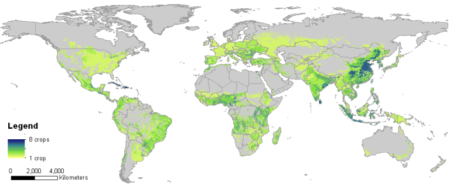

Since I’m on the subject of germplasm databases, I’ve also recently come across the Legume Information System, which focuses on material in the US genebanks. It has all kinds of data, but I just looked for germplasm from Italy to compare with what’s in Bari. Here’s the map for Medicago spp, showing growth habit in different colours (click on it to see it better).

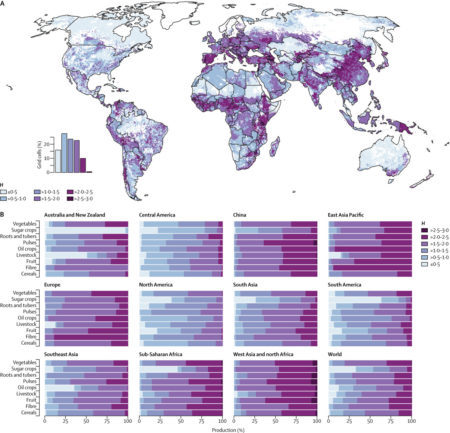

Compare and contrast with the ITA004 collection for the same species.

Which is why it’s a good idea to have all these data together in one place, i.e. Genesys.