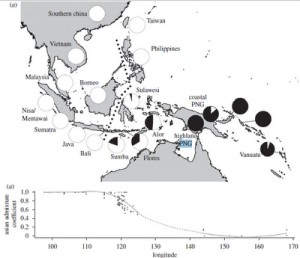

Dienekes’ Anthropology Blog has an intriguing map from a paper on human genetic diversity in island South East Asia showing a sharp cline across Wallace’s Line.

The genetic cline corresponds to a cline in phenotype which was actually recognized by Wallace himself. ((And for languages, see this.)) The authors…

…conclude that this phenotypic gradient probably reflects mixing of two long-separated ancestral source populations—one descended from the initial Melanesian-like inhabitants of the region, and the other related to Asian groups that immigrated during the Paleolithic and/or with the spread of agriculture. A higher frequency of Asian X-linked markers relative to autosomal markers throughout the transition zone suggests that the admixture process was sex-biased, either favouring a westward expansion of patrilocal Melanesian groups or an eastward expansion of matrilocal Asian immigrants. The matrilocal marriage practices that dominated early Austronesian societies may be one factor contributing to this observed sex bias in admixture rates.

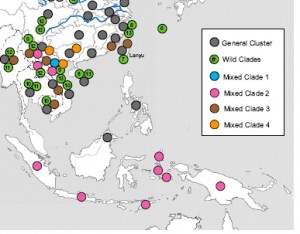

There’s a map of the same region in the recent paper on pig domestication that’s been in the news lately.

Compare and contrast. Still two quite distinct populations, but the placing of the line of demarcation is somewhat different. This is what the authors have to say about the Pacific pigs, after their main discussion, which is of their separately domesticated Chinese cousins:

This genetic evidence also supports separate domestication pathways (however independent) of one population in India and three wild boar populations indigenous to Peninsular Southeast Asia. Given the relative geographic proximity of the Southeast Asian clades, it is possible that the domesticated haplotypes were all present in a single population of wild boar, as is the case for modern Yaks. Regardless, only the Pacific Clade domestic pigs were transported out of Southeast Asia (to ISEA and the Pacific) before they were replaced in their homeland by domestic pigs derived from nonindigenous populations of wild boar.

So, people and pigs moving together across Wallace’s Line. How about crops? There are also distinct Pacific and Asian genepools in taro, though I could not find a nice map to compare directly with the above. However, the consensus seems to be — as also for crops such as bananas, yams, breadfruit, sugarcane and yams — that domestication happened southeast of the Wallace Line, in Sahul (Melanesia to be exact). As my friend and colleague Vincent Lebot said of these crops a few years back ((And I don’t think he has changed his mind!)):

We now have biomolecular evidence to suggest that most cultivars were not brought by the first settlers from the Indo-Malaysian region, but rather were domesticated from wild sources existing in the New Guinea and Melanesian areas… In other words, the first migrants that went across Wallacea did not embark major domesticated plants if any, in their adventure.

Pigs, in other words, and maybe chickens, but not taro or yams. Banana went in the opposite direction. I wonder why. Or did people bring them on their adventure, and abandon them when they found better varieties?

Incidentally, coconut also shows a bit of a Wallacean dividing line, but of course it doesn’t need humans for its dispersal, at least not everywhere.