- Frank Rijsberman aims to build a “strong Consortium.”

- Teaching tools aim to improve capacity in plant breeding. And no, I didn’t mean anything by the juxtaposition, settle down.

- Kenyan reality show aims to enhance rural livelihoods. What, are you trying to be funny? No, I tell you, it’s all a massive coincidence.

- You know what, why don’t we just all go to the beach and relax? Nothing like combining work with pleasure…

- You could read the new Plant Cuttings there.

- Or look at 3D photos of cabbages.

- Or fiddle with the latest geeky plant gadget.

- PDF of the European dictionary of domesticated and utilised animals. From the folks at the European Regional Focal Point for Animal Genetic Resources (ERFP). Which is news to me. Relationship to the equivalent on the crops side unclear.

- Speaking of Europe, someone at the Dutch genebank studying gaps in the conservation of crop wild relatives. Welcome to the club.

- Well this sort of thing is not going to help with any gap analysis, is it? Qualifies as assisted migration though, perhaps, which is kinda cool. And may well be needed.

- I wonder what the Brazilian forest code means for crop wild relatives.

- Traditional Japanese rice variety grown in Queensland to help Fukishima victims. Well, yes, but it’s not exactly charity we’re talking about here. And what’s it going to do to all the wild rice there? Which I’m willing to bet is a gap of some kind.

- Speaking of altruistic gestures, the idea to, er, sell the Indian genebank encounters some, er, opposition.

- No plans to sell anything from this new Jersey apple genebank. Except maybe the cider? I wonder, any hazlenut genebanks out there? No, don’t write in and tell me.

- The genebank of the SADC Plant Genetic Resources Centre given a bit of a face-lift on VoA. At least in the trailer, starting at 0:45. Not sure how to get the full thing, but working on it…

- Latvian government plants small veggie patch in meaningless gesture. Paparazzi promptly tread all over it. Not that such things can’t be nice, and indeed useful. Oh, and here comes the history. But maybe they should have taken a slightly different tack.

- “Orange is the colour of curry.” Why spice is nice. And here comes the science on that.

- And speaking of heat, FAO very keen to tell you what zone you’re in. Oh, hell, there go another couple hours down the drain as I try to navigate the thing.

The multifarious history of healthy oats

News of a healthy new oat variety sent me scurrying to the Pedigrees of Oat Lines (POOL) website at Agriculture Canada, but alas BetaGene is not there. However, our source on all things oats tells us of another US cultivar, released some years ago, called HiFi, which is also high in those heart-friendly beta glucans. Our source thinks HiFi was probably involved in developing BetaGene.

HiFi, by the way, includes a whole bunch of wild relatives in its pedigree, including Avena magna, A. longiglumis and A. sterilis. Interestingly, when you check up on that A. magna in GRIN, it turns out that the accession used, which was collected in Khemisset, Morocco in 1964, was originally labelled A. sterilis. It looks as though seeds of a couple of different species were inadvertently placed into a single collecting bag on that far-off summer day in North Africa. The mishap was only recognized when the material was later processed in the USDA genebank, which led to the original sample being divided up. Ah, the perils of crop wild relatives collecting! And ah, the value-adding that genebanks do!

Incidentally, there’s material from at least half a dozen different countries in HiFi’s 1 pedigree. And that, of course, 2 is the standard argument for both genebanks holding diverse collections, and a multilateral system of access to (and sharing of the benefits deriving from the use of) that diversity. Too bad that point is not made in any of the news items about the new variety that have been appearing.

I don’t really understand that. I think “the public” would find it interesting that their porridge, or whatever, includes genetic material from all over the world, and that people have been working very hard for many years to put in place the conditions to allow such sharing to continue. Including an international treaty, no less. Which should really be telling us these stories.

LATER: …as opposed to these.

Nibbles: Banana networking, Belgian flora, On farm breeding course, International collaboration, Wheat pre-breeding, Dog evolution

- ProMusa goes all social.

- Belgian flora goes online.

- Plant breeding goes to the people.

- FAO and ICARDA go together.

- Brits go all in on wheat pre-breeding.

- Modern dog breeds don’t go all the way back to the grey wolf.

Tomato expert’s field notes go online

We have blogged before about the C.M. Rick Tomato Genetic Resources Center at UC Davis and their tomato germplasm database. Now, via Dr Roger Chetelat, the director, we hear of a major addition to the data they make available.

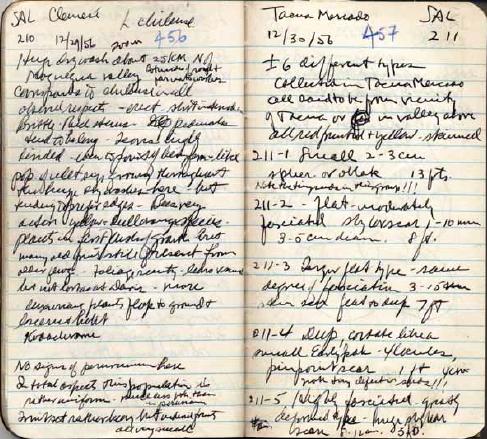

The collecting notes of Dr Charles Rick, the world’s foremost authority on tomato genetics, who passed away in 2002 and after whom the center is named, are now online. You can see an example here, for LA1253, a Lycopersicon hirsutum f. glabratum (or Solanum habrochaites if you prefer) collected in Ecuador in 1970. The notes have been painstakingly transcribed from Dr Rick’s handwritten field notebooks, an example of which you can see below. Cannot have been easy work. And I mean both chasing after all those tomato wild relatives in the first place, and transcribing Dr Rick’s notes after so many years and with him gone.

There are plans to eventually also “scan the pages that contain drawings of fruit shape, maps of collection sites, or other tidbits that can’t readily translated into text.” As an old collector, I find this stuff fascinating. Although I’m really not sure I’d like my own field observations so mercilessly exposed to the world.

Nibbles: Rio+20, Food security, Old seedsmen, New products, Camels, Informatics, Malthus lecture

- It’s so exciting: Rio+20 is almost upon us. Here’s the CGIAR’s Call to Action. Maybe they could fix the splits too?

- CIAT hopes to have some useful answers on food security and ecosystem services, in four years.

- At Chelsea, maybe the sun will shine on seedsmen of old?

- How they make flour from diverse agricultural products in Ethiopia video.

- They’re commercializing camels there too.

- Obituaries for bioinformatics tools. Stop sniggering in the back.

- Third annual Malthus lecture starts in just a few hours. In Washington DC.